Hospital Calls BERT to Calm Agitated Patients

Abstract

A hospital musters resources from several of its departments as part of a strategy to prevent minor crises from escalating into larger ones.

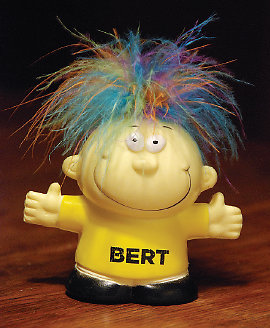

Goofy? Maybe. But an attention-getting device like a squeeze toy that says, “Have a stress-free day!” helps spread the word about one hospital’s new plan to calm agitated patients.

A Missouri hospital revamped its emergency response protocol to prevent agitated patients from becoming violent, but it took comprehensive planning and training—and some help from a squeaky yellow squeeze toy—to get the program off to a good start.

The goal was to create a group of skilled experts who could deescalate situations in which patients are in a behavioral crisis, said Lawrence Kuhn, M.D., medical director for behavioral health with SSM Health Care, a Catholic hospital system with seven campuses around St. Louis. The pilot site was SSM St. Mary’s Health Center in Richmond Heights, Mo.

Their goal was to establish rapport early, set limits for the patient’s choices, and minimize calling security officers to subdue the patient, he said at the APA Institute on Psychiatric Services in Philadelphia in October.

So St. Mary’s adapted a model from the Crisis Prevention Institute of Milwaukee to form the hospital’s Behavioral Emergency Response Team (BERT). “BERT is a three- or four-person collaboration between security, nursing, behavioral health, administration, and the hospital phone operators,” explained Sarah Lohse, R.N., B.S.N., the director of inpatient services.

The service is used only for patients. Visitors and other nonpatients in escalating crises are the responsibility of the security department alone.

The BERT goes into action when a patient is exhibiting verbal symptoms of anxiety or is in a defensive state, said Lohse. Physical acting out still calls for a security response.

The telephone operators are the system’s linchpins, she said. Once a special extension number is dialed, the operators send word over the staff paging system to BERT members on duty.

One team member grabs the “go bag,” filled with everything from pens and involuntary tracking forms to restraints, the latter rarely used, but always at hand.

“Behavioral health takes the lead, building rapport with the patient and documenting the encounter,” said Lohse. “We use security guards from the emergency department, so often they already know the patient, which also helps.”

The administrator on the team helps arrange the next steps for patients, linking them with services or admitting them, as necessary.

The need for some new thinking about how to handle patients in escalating crises began in 2010 when smaller psychiatric units in the region began to close and the county shut its sole psychiatric hospital.

As training for the BERT program began, clinicians, security officers, and administrators were joined by personnel from the emergency, information technology, and marketing departments. The marketing department developed a full package to spread the word about the new program: flyers, posters, screen savers, badge cards, and key chains.

Perhaps the biggest help was the odd little squeezable “stress doll” with the hysterical laugh—immediately named “BERT”—who swiftly became a favorite with everyone in the building and helped promote his namesake program (see photo). Little BERT even appeared as an icon on the telephone operators’ computer screens, to make clicking on him easier to start a team call. But the squeeze doll was just the symbol for a broader process within the hospital.

“We first trained the primary team responders, and then we educated the rest of the employees,” said Lohse, who led the training program.

So far, 166 BERT interventions have been called since the operation started in August 2012.

“Over that time, we’ve changed the culture from a power struggle to a therapeutic intervention,” said Kuhn. Restraints have been required on only six occasions.

Challenges remain, he noted. Fielding a full team when the whole staff is contending with a heavy patient load is not always easy. And employees have tended to wait too long to call for the BERT, said Lohse. “We continue to encourage them to call sooner rather than later.”

“Qualitatively, though, employees say they feel better and safer with BERT in place,” said Kuhn.

Ultimately, the BERT isn’t designed to solve every escalating crisis, Lohse explained, but it does provide an additional level of support to existing resources and helps create a culture that binds together hospital employees and departments to solve a common problem. ■

Information about SSM Behavioral Health Services is posted at http://www.ssmhealth.com/behavioralhealth.