Brain-Area Activity Might Predict Depression Treatment Response

Abstract

The level of glucose metabolism in the brain’s anterior insula may predict whether depressed patients are going to respond better to an antidepressant or cognitive-behavioral therapy.

Only 40 percent of patients with major depressive disorder achieve remission with their initial treatment. Thus it would be a great benefit if clinicians had a way to determine which treatments would help which patients before the treatment starts.

Such a tool may have been found, researchers suggested. It is the amount of glucose metabolism occurring in the anterior insula region of the brain.

Specifically, subjects with high levels of anterior insula metabolism were found to respond to an SSRI antidepressant, but not to cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT), while subjects with low levels of anterior insula metabolism were found to respond to CBT, but not to an SSRI.

The study was headed by, M.D., a professor of psychiatry, neurology, and radiology and chair in psychiatric neuroimaging and therapeutics at Emory University. The results were published online June 12 in JAMA Psychiatry.

Mayberg and her colleagues recruited 82 individuals with newly diagnosed, untreated major depressive disorder. They used PET scans to measure glucose metabolism in subjects’ brains. The subjects were then randomized to receive either the SSRI escitalopram or CBT for 12 weeks.

At the end of the 12 weeks, 65 of the 82 subjects had completed the experiment, and 38 had usable PET scan results and a clear-cut outcome regarding depression remission. Twelve subjects had remitted after receiving CBT, 11 had remitted after taking escitalopram, nine did not respond to CBT, and six did not respond to escitalopram.

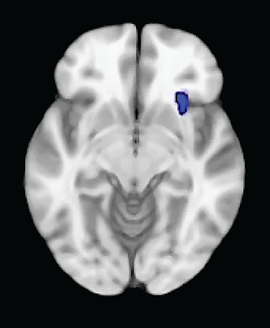

A PET scan showing the anterior insula region of the brain, which might be an objective marker to guide treatment selection for depressed patients.

The scientists then used the PET scan results obtained prior to treatment to determine whether the patterns of glucose metabolism in any brain areas might have predicted how subjects would respond to treatment.

Metabolism in the anterior insula appeared to have done so. Subjects who had responded to CBT, as well as those who had not responded to escitalopram, had experienced low metabolism in the anterior insula before treatment, whereas subjects who had responded to escitalopram, as well as those who had not responded to CBT, had experienced high metabolism in the anterior insula before treatment.

“Finding the insula was interesting, as it has certainly been repeatedly seen in imaging studies of depression and mood regulation more generally and shows reproducible changes with various treatments,” Mayberg said in an interview with Psychiatric News. “I personally expected a second pattern that would characterize all remitters independent of treatment type—a sort of general capacity-to-respond signal. But we didn’t find one.”

It thus looks as if metabolism in the anterior insula might be a marker to guide treatment selection for depressed patients, Mayberg and her team concluded. In other words, low metabolism would indicate that a patient would likely respond to CBT but not an antidepressant, while high metabolism would indicate that a patient would likely respond to an antidepressant but not CBT.

To verify this finding, however, a prospective study is needed. Mayberg and her colleagues have applied to the National Institute of Mental Health for a grant to conduct one. “There are several ways to set it up,” she said. “In a perfect experiment, one would compare remission rates in the group assigned to treatment based on their brain biomarker to a similar group given randomized treatment assignment….Patients would need to be blinded to the group to which they were assigned. This would be a prospective testing of the utility of the biomarker.”

If the biomarker turned out to be a useful tool, when might it become available to psychiatrists to use clinically? Although PET scans are already used clinically for some medical indications, including diagnosis of Alzheimer’s disease, they are not yet clinically used for other psychiatric indications, Mayberg noted.

The study was funded by the National Institutes of Health. ■

“Toward a Neuroimaging Treatment Selection Biomarker for Major Depressive Disorder” is posted at http://archpsyc.jamanetwork.com/article.aspx?articleid=1696349.

A biomarker, the level of glucose metabolism in the anterior insula area of the brain, may have been found that could predict whether a patient is going to respond to a particular depression treatment. | |||||

To ascertain whether such a biomarker could be a useful tool, a prospective study needs to be conducted. | |||||

Although PET scans are used for some medical indications, including diagnosis of Alzheimer’s disease, they are not clinically available for psychiatric indications other than Alzheimer’s. | |||||