Prolonged Adolescence Helps Build a Better Brain

Abstract

Teenagers are not weird creatures from distant planets; it only seems that way to their parents, says a leading NIMH researcher.

“Contrary to what most parents of adolescents believe, teens do have brains,” Jay Giedd, M.D., assured listeners at the American Association for the Advancement of Science (AAAS) headquarters in Washington, D.C., in June.

“They are not broken or defective adult brains, but they are different compared to those of children or adults,” said Giedd, a psychiatrist and chief of the brain imaging unit in the Child Psychiatry Branch of the National Institute of Mental Health.

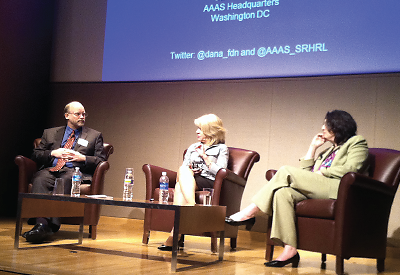

The way adolescents learn, play, and interact has changed more rapidly in the last 15 years than in the previous 500, but how that affects brain maturation is not yet clear, said Jay Giedd, M.D. (left), who spoke on a panel with Elaine Walker, Ph.D., and Elizabeth Albro, Ph.D., at the American Association for the Advancement of Science in Washington.

His talk was one in a series of discussions on advances in neurosciences cosponsored by the AAAS and the Dana Foundation.

Big changes occur in all social mammals during adolescence, which can give the impression of malfunction, said Giedd. Increased risk taking and sensation seeking are coupled with a move away from affiliation with parents and toward the peer group.

Evolution—and possibly an ancient change in climate from warm to cool—favored brain development as a survival tool. However, there was a tradeoff, he said. Building a better brain meant prolonging adolescence, when young humans can learn and the brain can stay plastic and adaptable. “There were huge costs but huge benefits too.”

Adolescents today may not be facing saber-toothed tigers, but the ways in which they learn, play, and interact have changed more rapidly in the last 15 years than in the previous 500, he said. Teens spend an average of 11 hours a day looking at their laptops, tablets, or smartphones, often at the same time. Everyone has immediate access to vast amounts of information, good or bad.

“But the jury is still out on what this means,” he said.

Furthermore, the effect on social interaction is unclear. Teens can share the same online experiences and connect virtually with lots of people around the world.

“But there’s little sensory input and less development of the social alliances that were so important during evolution,” said Giedd.

The brain does not mature by getting bigger but by becoming more connected within itself and more specialized, he pointed out. Gray matter and synaptic density build up during childhood, then decrease in a form of competition.

Speed increases as myelination proceeds during that process, but speed is not enough. “The timing is important too,” he noted. “You have to get the message to the right place at the right time.”

That’s how it is supposed to go, and it usually does, but for a minority of teenagers, the timing is not right, and a familiar list of psychiatric disorders crop up in adolescence and young adulthood.

If Giedd was largely hopeful about adolescents, another speaker, Elaine Walker, Ph.D., a professor of psychology and neuroscience at Emory University, said she felt like the “curmudgeon at the Optimist Club meeting,” in delving into the origins of adolescent-onset disorders like schizophrenia.

What the public saw in “A Beautiful Mind,” the book and movie about mathematical genius John Nash, was not at all typical of people with schizophrenia, she said. Most people who develop psychoses end up with low educational and social attainments.

Risk factors for schizophrenia include genetic and prenatal influences, but very likely also stressful childhood experiences that sensitize the brain, said Walker. “It’s like an amplified normal adolescent trajectory.”

“Every symptom you can imagine of adult schizophrenia can be predicted by the adolescent brain going too far,” Giedd agreed.

Longitudinal research, such as in the North American Prodromal Long-Term Study, might enhance the ability to identify at-risk individuals and shed light on vulnerabilities and the process that triggers the expression of serious mental illness, said Walker.

“With that kind of information, we would have a lot more leverage for interviewing to prevent psychosis,” she said. ■

An article by Jay Giedd, M.D., “Prenatal Growth in Humans and Postnatal Brain Maturation Into Late Adolescence,” is posted at http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3396505.