Genome Analysis Quantifies Risk Across Psychiatric Disorders

Abstract

A new genomic study puts numbers on the role genes play in various psychiatric disorders and the overlapping pathology between certain disorders.

By scanning the genomes of tens of thousands of patients and control subjects, researchers have quantified how much common single nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) variants contribute to the overall risk of five psychiatric disorders as well as the amount of overlap between the disorders.

The five disorders studied were schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, major depression, autism spectrum disorder (ASD), and attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD).

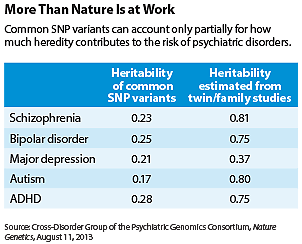

Heritable common SNP variants contribute about 17 percent to 28 percent of the risks of these disorders (see table), the study showed.

Schizophrenia and bipolar disorder had the largest genetic overlap in paired analysis between disorders, followed by correlations between bipolar and depression, between schizophrenia and depression, and between ADHD and depression. The correlation was low between schizophrenia and ASD and nonsignificant for all other pairings.

The numbers from this study represent low-end estimates because other types of mutations, such as rare variants and copy number variations, were not included, the researchers noted. For example, twin and family studies previously estimated that heredity overall contributes about 81 percent of the risk of schizophrenia, but this study estimated that SNP-based heritability contributes 23 percent of that risk.

This study is the second major publication from the Cross-Disorder Group of the Psychiatric Genomics Consortium. The first study, published February 28 in the Lancet, identified four chromosomal regions with mutations linked to all five psychiatric disorders (Psychiatric News, April 5). The group has been conducting genomewide association studies (GWAS) on data pooled from multiple countries. It receives funding from the National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH) and other governments, including those of Australia and the Netherlands.

Taken together, these cross-disorder genomic analyses add weight to the theory that each psychiatric disorder is not a single construct with an etiology and pathway distinct from other disorders. Rather, a disorder can be deconstructed into a combination of dysfunctions in various “dimensions” or “domains,” and some patients across different disorders may share the same pathology and genetic risks in a particular dimension, such as executive function or working memory. This is an area the NIMH has been intensively pursuing for the past few years through its Research Domain Criteria (RDoC) project.

“The best way to think about this is to imagine a house with many beams. When this group of beams or that group of beams break, the house would collapse in ways that look different from the outside, but inside it may be that some of the same beams have broken,” Bruce Cuthbert, Ph.D., who is heading the RDoC project, explained in an interview with Psychiatric News. He is also the director of the NIMH Division of Adult Translational Research and Treatment Development.

“The GWAS data are consistent with the RDoC framework,” Cuthbert said. For example, the study shows that the magnitude of variability between schizophrenia and bipolar disorder is about the same as the variability within bipolar data, which supports the notion that schizophrenia and bipolar share much of the same genetic etiology. Also, “there is tremendous variability within a disorder,” which is consistent with the multidimensional nature of each disorder, Cuthbert pointed out.

Genomewide analyses have not been able to pinpoint the genetic causes of major psychiatric disorders, the researchers said, not because the culpable risk mutations do not exist, but because there are many risk mutations scattered throughout the genome, each contributing a small effect to the overall risk. Therefore, a huge number of samples are needed to achieve adequate statistical power.

The five psychiatric disorders have been included in the cross-disorder group’s analyses to date because “these are the disorders for which large-scale collaborative efforts have been able to collect the needed genomic data,” Kenneth Kendler, M.D., one of the lead authors of the study and a professor of psychiatry at Virginia Commonwealth University, told Psychiatric News.

As more samples in other disorders are added to the datasets, “we have new disorders joining [the future studies], including drug abuse, obsessive-compulsive disorder, and possibly eating disorders,” Kendler said.

As incomplete as the current GWAS discovery is, heritable risks are only a part of the pathophysiology of psychiatric disorders. Disease-triggering environmental factors and gene-environmental interactions remain mostly unknown. Other research methods are needed to clarify the sources of environmental risks, Kendler noted.

An abstract of “Genetic Relationship Between Five Psychiatric Disorders Estimated From Genome-Wide SNPs” is posted at http://www.nature.com/ng/journal/vaop/ncurrent/full/ng.2711.html.