Shift to Population Health Called Critical to Psychiatry’s Future

Abstract

The high cost of treating patients with psychiatric disorders and chronic physical illnesses are driving the push to replace “complaint-driven” care with population-based collaborative care.

“Population health” is the future.

So say the leaders and champions of the emerging models of collaborative care. While there will always be a place for solo private-practice medicine—and a need for clinicians who know how to deliver one-on-one clinical care for the patient’s complaints—those champions argue that the traditional model of ad hoc, individualized care must give way to one that personalizes care by data-driven, evidence-based decisions, in addition to the wisdom of the clinician and the doctor-patient relationship.

“Population health is a conceptual framework for thinking about why some populations are healthier than others and what kinds of policy development, research agenda, and resource allocation should flow from the [fact that] some populations are healthier than others,” said psychiatrist Joseph Parks, M.D., director of Missouri’s Medicaid program, in comments to Psychiatric News. “At a more operational level, it is the health of a population as measured by health status indicators, but as it is also influenced by social, economic, and environmental factors; personal health practices and behaviors; individual capacities; human biology; and of course, the health services that people get.

Joseph Parks, M.D., director of Medicaid in Missouri, says many Medicaid directors are turning to psychiatrists for help with high-cost patients who have psychiatric disorders and chronic medical conditions.

“Population health can be thought of as the intersection and combination of clinical care and public health,” he explained.

As medical director for Missouri’s Department of Mental Health, and now as director of Medicaid, Parks has been a national leader in integrating psychiatric and general medical care for the state’s publicly insured patients. He will be speaking about population health and how it applies to psychiatrists working in integrated, collaborative care models later this month at APA’s Institute on Psychiatric Services in San Francisco. He previewed his talk in an interview with Psychiatric News.

Parks believes the biggest weakness of the current delivery model is that it is “complaint driven”—that is, it depends on the individual patient to come to the system with a complaint. “So we are depending on the sick person who is least educated about health care to figure out what he or she needs and when,” he said. “This is particularly problematic in psychiatry, when the illnesses we deal with interfere with concentration, executive function, persistence on task,” and other factors that may hinder the ability to even recognize that one is ill, let alone to seek out timely, evidence-based treatment.

In contrast to this individualized, complaint-driven model, population health is data driven, Parks said. “We use data to try to predict before illness happens, or at least pick out people who have known care gaps—people we know should be getting treatment—and try to reach out to them before they get sicker and need the emergency room. That’s the process of what’s called ‘risk stratification’—figuring out the patients who are at higher and lower risk so you can target the limited resources toward the people who need them.”

Health systems that are invested in collaborative care use “registries” to risk stratify the patients within the population they serve. These are databases listing patients and their important health indicators and conditions, as well as evidence-based treatments to address those conditions, so that clinicians working on the collaborative team know which patients need which kinds of tests, treatments, or interventions.

Registries can also be used to benchmark the performance of clinicians in providing those tests and interventions. “Population health management, through the use of registries, gives the individual practitioner constant feedback about what their peers are doing and how what they are doing compares with those peers,” Parks said.

Ultimately, he said, it “takes medicine and psychiatry from being a ‘cottage industry’ where we do what we guess is best, to a quantifiable, data-driven science.”

If it sounds visionary, Parks is confident that two realities—data on costs showing that mental illness and substance abuse are the main drivers of high utilization and a shortfall of psychiatrists necessary to meet the demand for services—are causing payors to recognize that the “cottage industry” doesn’t work and that psychiatric expertise is essential in a reformed, collaborative care model.

“I recently went to a national meeting of Medicaid directors, where all of them were asked what they most wanted to talk about,” Parks recalled. “Two-thirds of them indicated they wanted to hear about behavioral health. And that’s because they’ve been running the data, and when you run the data, it is the patients with behavioral health conditions who are the highest utilizers of not only behavioral health services but of general medical care. They have more hospitalizations; more admissions for asthma, diabetes, and heart disease; and more use of the ER for all medical causes.

“So the payors in the commercial and public sectors have come to realize that patients with behavioral health conditions are the expensive ones driving the total spend,” he said. “[Payors] want to control the total spend, so they are looking to us now for answers.”

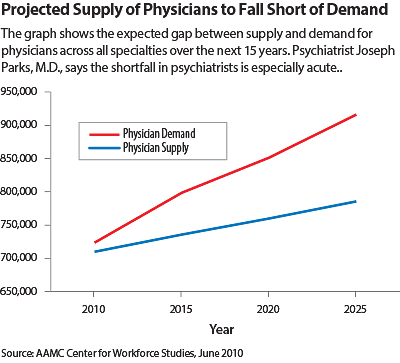

But that raises another problem and another reason why there is a certain inevitability to population-based, collaborative care—there are not enough psychiatrists to meet the demand for mental health services. Parks has data showing that the current and future projected numbers of psychiatrists falls short—and will continue to fall shorter—of the need for services.

“Our current delivery model will fail because we can’t possibly provide services to everyone who needs or wants our services,” Parks stated (see chart on page 5).

But the collaborative care model—as exemplified, for example, by the IMPACT model implemented at the University of Washington—repositions the psychiatrist as a consultant advising primary care physicians, care managers, psychologists, and social workers about best practices for an entire population. In this way, as Jürgen Unützer, M.D., one of the founders of the IMPACT model, has said, it exponentially increases the clinical reach of the psychiatrist—and her or his value to the health system.

“Population health means thinking of your patients not just as the people you are seeing face to face in the clinic, but as everyone that the clinic serves, and everyone trying to get into that clinic,” Parks said. “We will never meet the demand with our current numbers. That’s why psychiatry should care about population health—because it is the only way we can improve the health of all the people who need and want our services.” ■

An interview of Parks by Psychiatric News can be accessed here.