Media Crime and the Real Thing May—or May Not—Coincide

Abstract

Forensic psychiatrists, judges, and criminologists examine clues at the intersection of mass media and violence.

The argument over the relationship between media and violence is as old as ancient Greece and as new as the epidemic of recent school shootings. Two sessions at the American Academy of Psychiatry and the Law’s annual meeting in Chicago in October looked at that connection in different ways.

One examined how media consumption affected juries’ expectations, while the other discussed the contentious issue of whether the media cause violent behavior.

In the first, two researchers explored the alleged “CSI effect.”

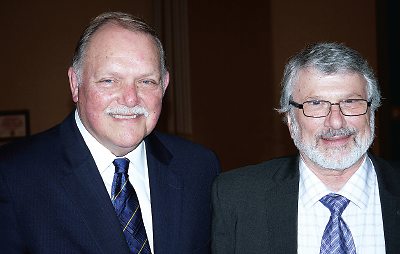

Juries may be less swayed by crime shows on television than some people think, according to Donald Shelton, J.D., Ph.D. (left), and Gregg Barak, Ph.D.

CSI—the television drama about crime-scene investigators—and its spinoffs are among the most popular shows on television, said former judge Donald Shelton, J.D., Ph.D., director of criminal justice studies at the University of Michigan–Dearborn. During the show’s 15-year run, many prosecutors, defense attorneys, and judges have speculated that it has influenced jurors’ expectations about the presentation of scientific evidence in the courtroom.

Trying to tease out cause and effect, Shelton and Gregg Barak, Ph.D., a professor of sociology, anthropology, and criminology at Eastern Michigan University, surveyed members of jury pools in Ann Arbor and Wayne County (Detroit), Mich., about their TV-watching habits and their expectations about evidence in trials.

About 58 percent of the jurors wanted to see scientific evidence—like fingerprints or DNA—in every criminal trial, with even higher rates for more serious crimes like murder or rape.

Nevertheless, those juries found defendants guilty more often on the basis of eyewitness testimony than scientific evidence, despite studies demonstrating the highly variable accuracy of eyewitnesses.

Evidence Doesn’t Back CSI Effect

In fact, the CSI effect seemed to vanish under the data they collected, said Shelton.

“Watching CSI-type shows had no effect on whether a jury would require scientific evidence to convict,” he said. “And there was no difference between watchers and nonwatchers. The empirical evidence indicates there is no relation between convictions or acquittals and watching these shows.”

However, if bringing scientific evidence into the courtroom isn’t warranted, prosecutors should at least explain to juries why it is not relevant to the case, said Shelton. “There’s a danger that prosecutors who believe in the CSI effect will present junk science to fill the void.”

Also, judges should screen any scientific evidence before it is presented in court, carefully oversee jury selection, and control instructions to juries on how to weigh scientific evidence, he said.

Talking about a CSI effect is thus too simplistic, said Shelton and Barak. They suggested two other possibilities for the persistence of beliefs to the contrary.

“First, there’s the ‘tech effect,’ ” said Shelton. “The more sophisticated the technologies the jurors used in their own lives, the more they expected scientific evidence.”

Then there’s the “CSI myth effect,” added Barak. “No matter what the data say, prosecutors, defense attorneys, and judges still think simplistically about how jurors think,” he said. “They believe jurors can’t differentiate between media and reality, but jurors are more sophisticated than the criminal bar believes.”

Ancient Argument Still Relevant Today

Whether media depictions of violence cause the real thing is an old argument.

Plato and Aristotle had two visions of the effects of “media” violence on the population, said Jeff Trexler, J.D., associate director of the Fashion Law Institute at Fordham University Law School in New York.

Plato believed in “mimesis,” that life imitated art. He argued that the popular culture of the day—like the Iliad and the Odyssey—were filled with violence that would only encourage real violence in the streets of Athens, said Trexler.

Aristotle responded that violence in plays or poetry offered “catharsis,” a way for audiences to work out violent feelings safely by watching them on stage.

And the evidence for and against links between modern media and violence remains shaky, maintained panelist Vasilis Pozios, M.D., a forensic psychiatrist with MHM Services in Harrison Township, Mich. Better understanding is limited by a dearth of research.

After the shootings at Sandy Hook Elementary School, several of the gun-control bills introduced in both the House and Senate included language authorizing research into the posited nexus between violent media—mainly movies and video games—and violent behavior. None of the bills was enacted.

Part of the problem in assessing possible links between violence and the media is that attention gets focused on extremely rare events, like mass shootings, said Praveen Kambam, M.D., an assistant clinical professor of psychiatry at the University of California, Los Angeles. Popular perceptions are colored by hindsight bias and a desire to find a single cause for violence, and population risk factors that initially appear to connect media and real-life violence do not translate well to individuals.

A public-health approach to evaluating the issue would embrace a multifactorial strategy, suggested Kambam. “Be careful of political agendas,” he cautioned. “Put probability and risk into perspective, but realize that the limitations of existing studies do not mean discarding them completely.” ■