Creative Use of Community MH Resources Saves Money, Improves Care

Abstract

Mental health experts call for multilevel strategies to build and improve community-based mental health options.

Community involvement is the key to better, more efficient, less costly mental health care in the United States as parity and the Affordable Care Act take hold, said speakers at a briefing in Washington, D.C., last November.

The final parity rule, issued in November 2013, “brings mental health out of the closet” and symbolizes the field’s inclusion in the greater health care system, said Michael Fitzpatrick, outgoing executive director of the National Alliance on Mental Illness (NAMI) at the briefing. The briefing was held to introduce Connect 4 Mental Health (C4MH), an initiative to build support for mental health care using “locally driven strategies that aim to help individuals with serious mental illness, their families, and the communities in which they live.”

“The parity rule is potentially revolutionary, but it will take years of effort to implement,” he said.

People with serious mental illness need more than insurance reform, said others.

“They rarely need just one service provided excellently,” said Paul Barry, M.Ed., executive director of MHA Village in Long Beach, Calif. “True, housing first is an improvement over hospitalization first, but you have to consider myriad factors that go into comprehensive wrap-around services.” For instance, since work is a primary source of individual identity, the Village offers its residents a variety of employment from day labor to agency-run businesses (like a cookie shop) where people on the way to recovery can build skills and demonstrate that they are assets in the working world.

One critical element in any jurisdiction is reversing the trend toward locking up people with mental illness for minor offenses or leaving them homeless rather than directing them to care, said Leon Evans, president and CEO of the Center for Health Care Services in Bexar County, Texas. Eventually, under a federal grant, the county was able to divert 16,000 people a month from the criminal justice system to treatment services.

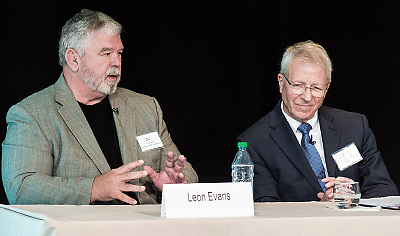

Leon Evans (left), of the Center for Health Care Services, says that a variety of community-based diversion and treatment programs can save money and improve outcomes for people with mental illness. At right is Bruce Bird, Ph.D., of Vinfen.

“You need a community collaboration,” said Evans. The “black-robe effect” helps a lot—putting a judge in charge of convening consumers, families, law enforcement officials, hospitals, and the medical system. “We need to learn to speak each other’s languages and build trust,” he said. However, merely articulating mental health needs to legislators who hold the purse strings isn’t enough.

“You also have to sell the system as ‘saving money’ and promoting ‘public safety,’ and you need the data to back that up,” said the Village’s Barry.

But sharing clinical outcomes information and cost savings is just the start, Barry noted. Agencies were not always good at stopping practices that were not very helpful for people with mental illness. “So you also have to challenge providers to do their work better and differently,” he said.

That challenge applies to others in the system too.

In the first crisis-intervention training in Bexar County, police officers were skeptical of “hug-a-thug” deescalation techniques emphasizing the use of verbal interventions before resorting to force. However, by the end of the course they were believers, said Evans.

The county also built a 24-hour crisis center to which the police can take people with severe psychiatric symptoms instead of to jail. The Restoration Center offers detoxification and substance abuse services as well. These diversion programs eliminated the need for a proposed new 1,000-bed jail.

Finally, technology may offer another adjunct to the spectrum of community-based care, said Bruce Bird, Ph.D., president and CEO of Vinfen, in Cambridge, Mass. Bird’s company and several Massachusetts mental health care organizations have a Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services grant to test the Health Buddy, a small electronic device that prompts patients with individualized questions about physical and mental health issues. Nurses at a central location can monitor the daily reports and intervene if the patient seems to need help.

C4MH is a project of NAMI and the National Council for Behavioral Health, in conjunction with Otsuka America Pharmaceutical and Lundbeck. The initiative seeks to encourage deeper discussions about mental illness and promote changes in the approach to mental health services in local communities, with an emphasis on “early intervention, creative use of technology, service integration, and enhanced continuity of care.” ■

Information about the Connect 4 Mental Health (C4MH) is posted at http://connect4mentalhealth.com.