New DSM Guide Describes Changes to Eating, Elimination, Sleep Disorders Criteria

Abstract

Important changes to eating disorder criteria described in the new volume for the general public include the addition of binge eating disorder and elimination of amenorrhea as a criterion for anorexia.

DSM-5, released in 2013, has been widely purchased and perused by professionals and members of the public. But as a guide to really understanding mental disorders for those not professionally trained, it’s not quite enough—or maybe a little too much. That’s why in May, American Psychiatric Publishing will issue a new volume: Understanding Mental Disorders: Your Guide to DSM-5.

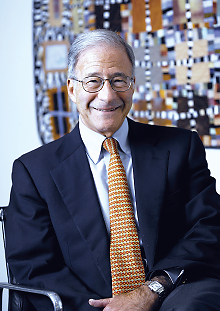

David Kupfer, M.D., chair of the DSM-5 Task Force and a member of the advisory panel for the new consumer guide, says it will help patients and families communicate with health care providers and each other.

“I think DSM-5 can be considered a reference tool for everyone, including patients and families, but it’s not intended as a guide for laypersons,” said David Kupfer, M.D., chair of the DSM-5 Task Force, which oversaw the long research endeavor that resulted in the clinicians’ guide. “It’s a bit too complicated, and what we knew would be needed was something that embraced the key concepts of the clinicians’ manual but also provided a translational piece to bring those concepts into a more common language so that patients and their families can communicate with their health care providers and each other.”

Kupfer is also one of a six-member panel of editorial advisers who oversaw the writing and editing of the new layperson’s guide. In addition to patients, families, and the general public, others who will find the book useful include nonpsychiatric health care professionals, teachers, counselors, clergy, employers—anyone who deals with people and needs to know more about mental illness and its treatment.

(For descriptions of the first six chapters of the guide, see previous issues of Psychiatric News.)

The seventh through ninth chapters describe eating and feeding disorders, elimination disorders, and sleep-wake disorders.

There are several major changes in DSM-5 for eating disorders of which patients and families will want to take note, including the elimination of amenorrhea from the criteria for anorexia nervosa. (An important feature of the new guide is that many chapters include an illustrative patient story, drawn from real-life clinical vignettes, with names and other identifying information removed. To read “Helena’s Story” about a teenage girl with anorexia, see box at right.)

Helena’s Story

Helena was a 16-year-old girl who lived at home with her parents and younger sister. Throughout her teenage years, she had been normal weight, but she worried a great deal about her body weight and shape. She often compared her body weight with that of other girls and women she met or saw—and then judged herself as too heavy.

Often, Helena checked her body weight by looking in the mirror.… At 15, she decided to become a vegetarian and began to cut out many foods from her diet. She was 5 feet 6 inches tall and weighed 125 pounds at age 15, but by her 16th birthday she had dropped to 110 pounds…. Time spent on her weight concerns took the place of other activities she used to enjoy, such as school work and having fun with friends. She became more alone. And she kept losing weight. Her parents became more alarmed about her weight loss and behavior. They talked about this between themselves and started watching and checking her eating behavior at meals. They urged her to eat more often, without success. She kept losing weight, and six months later she weighed 98 pounds. Helena appeared very thin. She often was withdrawn, hard to talk to, and distracted. She seemed weak—but did heavy exercise twice each day. She preferred to stand or pace rather than to sit and relax. Because of their concerns, her parents took Helena to see the family doctor for an evaluation. Helena was diagnosed with anorexia nervosa, restricting type. Her low food intake, low weight (BMI of 15.8), frequent exercise, and constant concern about her body weight despite being very thin are hallmarks of the diagnosis.

Perhaps the most noteworthy change to the chapter on eating disorders is the inclusion of a new diagnosis—binge eating disorder—for individuals who experience persistent, recurrent episodes of overeating marked by loss of control and significant clinical distress.

In an interview with Psychiatric News in 2013, Timothy Walsh, M.D., chair of the DSM-5 Work Group on Feeding and Eating Disorders, said an enormous amount of research in the last several decades justifies the inclusion of binge eating disorder. Walsh said the criteria—which describe persistent episodes of overeating at least once a week, marked by loss of control and clinically significant distress—are sufficiently restrictive to differentiate the diagnosis from the kind of periodic overeating that is normative in contemporary society.

The new guide describes binge eating disorder as follows: “People with binge-eating disorder often eat unusually large amounts of food. This overeating is often done in secret. People with the disorder can’t resist the urge to eat and feel shame and guilt once they stop. Unlike bulimia nervosa, the binge episodes are not paired with purging through vomiting or other means.”

Kupfer, in an interview with Psychiatric News, said the eating disorders chapter will be of great interest to parents, young people, primary care clinicians, and educators. “I think what is particularly exciting is that even in the relatively short period since DSM-5 was published, we are beginning to see the validation of these new disorders as well as the development of new potential treatments for binge eating,” he said.

Elimination disorders, describing disorders predominantly seen in young children, will likewise be of interest to parents. The new guide explains that “[p]eople with elimination disorders have problems urinating (passing urine from the bladder), called enuresis, or defecating (passing stools from the bowels), called encopresis. They pass their urine or stools into bedding, clothing, or other inappropriate places. Both disorders can occur during the day or at night. A person can have one or both disorders at the same time. These disorders are most often first diagnosed in children, after the age when a child is expected to be toilet trained. The disorders occur less often in teens and adults.”

An important feature of the new guide is the inclusion throughout the book of user-friendly tips for self-care and management of psychiatric conditions, even when under the care of a professional. So for elimination disorders, for example, the book offers the following helpful hints to parents of children who have enuresis or encopresis:

When accidents happen, maintain a neutral and matter-of-fact, problem-solving attitude. This helps the child not to be afraid of reporting accidents.

The child who had the accident can help with the cleanup of soiled bedding and clothing in age-appropriate ways, such as putting soiled clothes in the washing machine, cleaning himself or herself as best he or she can, or helping to put clean sheets on the bed. These tasks are performed by the child to help him or her take part in getting better, not to punish the child.

Parents need to be supportive and patient and reward the child when even slight progress is made.

Solving the problem together can help the parent and child learn new skills and increase their bond.

In DSM-5, a fundamental theoretical and organizational change also was made in the criteria for sleep-wake disorders—namely, the removal of causal associations between sleep disorders and the medical or mental disorders with which they frequently co-occur. That is, sleep disorders may exist independently of the medical conditions and warrant clinical attention in their own right.

The chapter in the layperson’s guide details the following sleep-wake disorders: insomnia disorder, narcolepsy, breathing-related sleep disorders (obstructive sleep apnea, hypopnea, central sleep apnea, and sleep-related hypoventilation), and parasomnias (non–rapid eye movement sleep arousal disorders, nightmare disorder, and rapid eye movement sleep behavior disorder). Also described briefly are hypersomnolence disorder, circadian rhythm sleep-wake disorders, and restless legs syndrome.

“So much progress is being made in the area of sleep disorders,” Kupfer told Psychiatric News. “The chapter in the new layperson’s guide is a good primer for patients and primary care physicians so they can very quickly get their hands on the facts. There are several distinctly different sleep disorders, so there is an important differential diagnosis that needs to be made, and good treatments are available.” ■

More information on Understanding Mental Disorders, including pre-ordering information and links to previous articles in Psychiatric News about the content, can be accessed here.