APA to Provide Framework to Evaluate Mobile Health Apps

Abstract

Though not giving outright recommendations, this new framework will help patients and clinicians make informed choices when picking apps to monitor or manage mental health.

Mobile phone apps can serve as an adjunct to mental health treatment, enabling patients to monitor or manage their condition and engage them further in the therapeutic process.

But which app should a patient use? There are thousands of mental health–related apps available for download on both Apple and Android devices, and many of these apps employ descriptions that make bold claims. Some are undoubtedly useful, but others could potentially be dangerous.

To help APA members and other practitioners navigate the turbulent ocean of mobile applications, APA has developed and posted the “App Evaluation Model” on its website. It is based on a theoretical evaluation framework developed by APA’s Smartphone App Evaluation Work Group, according to Steven Chan, M.D., M.B.A., the vice chair of the work group and a clinical informatics and digital health fellow at the University of California, San Francisco.

While physicians are familiar with evaluating medications or behavioral therapies, an app requires considerations beyond those employed for a typical clinical intervention.

“You have a lack of standardization, a lack of sound methodology, and a lack of data interoperability among these thousands of choices,” Chan said. “On top of that, there are hordes of privacy issues that have to be considered.”

And there isn’t much guidance that providers can turn to, said John Torous, M.D., co-director of the Digital Psychiatry Program at Harvard-affiliated Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center in Boston and chair of APA’s Smartphone App Evaluation Work Group.

The FDA, for example, assesses risks only in apps that are specifically designed to turn a phone into a medical device or into an accessory to a medical device (for example, to measure heart rate or brainwaves). The Federal Trade Commission has pursued some app manufacturers for making false claims, but only in cases of explicit medical dishonesty.

Other independent groups like PsyberGuide try to provide objective reviews for apps and other health technologies like wearables, but Torous noted that PsyberGuide has reviewed only a fraction of available mental health apps. “These apps become updated and outdated so quickly that one can’t even be sure if a particular review is even still valid,” he said.

As for the reviews on the app stores themselves, Torous stated that those likely do not reflect apps’ overall quality and should be read with some skepticism. Regarding reviews that are posted in app stores, Torous said that they are informal commentaries written by nonprofessionals and often do not reflect overall quality, validity, or usefulness.

Given the shortcomings of other efforts to rate apps, APA’s new evaluation model does not give static scores to apps. “Besides the problems related to the number of apps and their continual updates, the value of any application also depends on the context for each patient at hand,” Torous said. “This approach uses risk-based decisions that ask pertinent questions about the app design and capabilities that a doctor can discuss with a patient to make an informed decision.”

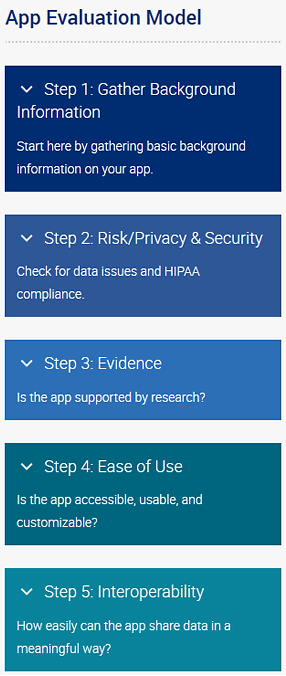

The App Evaluation Model features five levels of evaluation. The ground level, or “Step 1,” involves basic questions about the app such as cost and the name of the developer. After that are four sequential topics related to the benefits and risks of using the app: privacy and safety, efficacy, ease of use, and data sharing.

Each of these four topics contains a set of questions that a physician and patient can review together. For example, the privacy section includes questions such as “What security measures are in place?” and “Can you opt out of data collection?” Based on how the answers reflect patient desires, each topic is then given a green, yellow, or red designation. Like traffic signals, these color designations suggest whether it’s safe to proceed, whether some caution should be taken moving forward, or whether it’s better to stop and think about a different app.

It may seem like a lot of effort to find one useful app, but Chan thinks it can be a valuable learning experience for psychiatrists while picking up some technological savvy. Besides, some evaluations probably won’t take long. The four areas are presented in an ordered manner so that if privacy/safety is unsatisfactory, then the app should probably not be used.

“One of the first questions we pose is, does the app have a privacy policy? This is a critical item for any medical application,” Chan said. “There was a study in JAMA [Blenner et al., March 8, 2016] that explored diabetes apps and found that only 19 percent had a written privacy policy, so that’s an easy way to remove a lot of apps from consideration.”

The model and its guiding questions are posted on the APA website. Down the road the work group plans on including a handful of evaluations of well-established mental health apps as examples. ■

The APA app evaluator can be accessed here.