Origins of Violent Behavior Continue to Be Challenging to Pin Down

Abstract

The possible neuropsychiatric influences on violent behavior must be carefully teased out of a patient’s history.

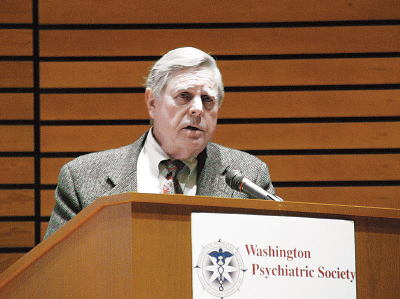

James Merikangas, M.D., has spent a lot of time in prisons.

There is plenty of evidence but not enough research on the association between neuropsychiatric disorders and violence, according to James Merikangas, M.D.

Not, of course, as an inmate, but as a consulting neuropsychiatrist in more than 100 death penalty cases during his career, said Merikangas, speaking about what he has learned from his time behind bars at the Washington Psychiatric Society’s Presidential Symposium on Violence Risk Reduction at St. Elizabeths Hospital in February.

His experiences have given him some insights into the origins of violent behavior on the part of the accused and convicted criminals he has evaluated or treated.

For instance, most of the people he has seen on death row had experienced parental violence as children, said Merikangas, a clinical professor of psychiatry and behavioral science at the George Washington University School of Health Sciences in Washington, D.C.

“The mix of child abuse, brain damage, and mental illness is a lethal combination,” he said.

In adulthood, a history of prior violence or aggression, drug abuse, traumatic brain injury, psychopathology, or schizophrenia with comorbid substance use are also risk factors for violence.

Merikangas wants every bit of information he can find on the people he evaluates: personal, family, medical, social, educational, vocational, and military histories, as well as the specific circumstances that led to the crime, when possible. He requires a complete physical examination, including a neurological workup and a psychiatric interview. He orders blood and urine tests and calls for MRI, EEG, and PET scans. Neuropsychological exams are “extremely valuable,” he said.

He looks, too, for neurologic soft signs. A high arched palate is associated with ADHD; an abnormal palmomental reflex with frontal lobe disease; loss of a sense of smell with dementia; and a short philtrum, hypertelorism, and sunken glabella are signs of fetal alcohol syndrome.

A differential diagnosis for violent behavior also includes inquiring about any congenital mental deficiency syndromes; developmental disorders; exposure to infections, toxins, brain trauma, or abuse; or psychiatric diagnoses.

Meningitis, measles, or encephalitis, for instance, may lead to brain damage and lack of judgment or control. Lead or alcohol exposure can be precursors to conduct disorder or ADHD. Conduct disorder as a child is associated with a tenfold increase in the likelihood of violence as an adult, he said.

Depression probably plays an underappreciated role as a source of violence, said Merikangas.

“Depression is a thought disorder, as well as a mood disorder,” he said. “It’s not just sadness.”

Metabolic disorders, like hypoglycemia and thyroid abnormalities, should be checked out as well.

Merikangas emphasized that his observations drew on his own encounters with defendants, prisoners, and ex-cons. The field needed a stronger research underpinning than one person’s observations, he said.

At present, research has been slowed by several obstacles: Sampling is biased by the refusal of states to allow full surveys of subjects. Confidentiality and privacy issues hamper full exploration of cases, especially during ongoing legal processes. Even the facts of each crime may be uncertain.

“You can’t simply ask prisoners, ‘What did you do?,’ because the answer may be used against them in court,” he said. “Or they might be lying.” ■

The Washington, D.C. Psychiatric Society’s website can be accessed here.