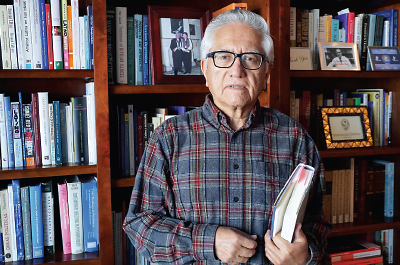

Renato Alarcón: Long-Time Advocate for Cultural Awareness in Psychiatry

Abstract

Witchcraft? Chemical imbalance? Culture shapes how patients experience and describe symptoms, this expert says.

As a young Peruvian-born and educated physician, Renato Alarcón, M.D., bumped into cultural challenges both personally and professionally when he came to the United States in 1967 for a fellowship in psychosomatic medicine at the Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine.

Renato Alarcón, M.D., is a co-developer of the DSM-5 Cultural Formulation Interview, which helps clinicians account for the influence of culture in their clinical work, improve patient-clinician communications, and ultimately improve outcomes.

“On hearing my accent, patients may have wondered how much I knew or could understand about their concerns,” he recalled.

“I noticed that clinical presentations placed little emphasis on patients’ race, ethnicity, religious beliefs, or other cultural factors,” Alarcón said. “As an international medical graduate, encountering cultural differences myself, I thought those variables needed more attention.”

Culture affects how patients experience, explain, and report disturbed thoughts, feelings, and behaviors, he said. Some people attribute depression, anxiety, or other symptoms to witchcraft. Some somaticize, converting mental distress into pain and other bodily symptoms. Others say they have a chemical imbalance. In each instance, Alarcón said, patients have interpreted their symptoms through the prism of their culture.

Alarcón stayed at Hopkins until 1972, completing his residency in psychiatry and a fellowship in clinical psychopharmacology and earning his M.P.H. there.

He went on to a distinguished career in academic psychiatry, first in Peru, and then after he returned to the United States in 1980, seeking to enlarge understanding of the impact of culture on psychiatric diagnosis and treatment and improve global mental health. Now emeritus professor of psychiatry and psychology at the Mayo Clinic College of Medicine, Alarcón talked recently with Psychiatric News about what cultural psychiatry is—and is not.

Taking culture into consideration enables psychiatrists to depathologize behaviors they might otherwise view as symptomatic, Alarcón said, and to obtain a fuller picture of what patients are experiencing. Knowing patients’ traditions and beliefs may allow psychiatrists to employ culture in a psychotherapeutic role, by building rapport and collaboration, he suggested.

Cultural knowledge also may benefit treatment and prevention, he said. Encouraging some patients to participate in religious or other social rituals, for example, may help ease their distress and prevent relapse.

Cultural psychiatry is not a subspecialty, Alarcón asserted. Cultural understanding should be an integral part of the education and practice of every psychiatrist, he said. It is relevant to all patients, not only those who are immigrants or members of minority populations. The cultural identity of a person reared in Manhattan, for instance, likely differs considerably from that of a person reared in the Mississippi delta.

Cultural psychiatry is not anti-biological, he noted. Cultural understanding adds to that derived from knowing the neurobiological substrates of an illness. “All psychiatrists,” he said, “should strive to foster bio-psycho-socio-cultural-spiritual health in their patients.”

As a member of the DSM-5 study group on gender and cross-cultural issues, Alarcón helped develop the Cultural Formulation Interview, a set of 16 brief culture-focused questions to aid in mental health assessment. He also helped amend the now-outdated concept of culture-bound syndromes and refine information on the handful of disorders included in the DSM-5’s Glossary of Cultural Concepts of Distress.

“One often hears physicians say all patients should be treated the same way. But reality is not like that,” he noted. “Racism, sexism, and other forms of discrimination still exist, and stigma is a universal phenomenon.”

Even psychiatrists may hold stereotypes based on a patient’s country of origin, color, gender, socioeconomic status, or other characteristics, he noted, and may assume a person’s cultural load is unchangeable.

“The important thing,” he asserted, “is to understand the human entity, the patient’s background, why he or she comes to see you now but didn’t come earlier, and how he or she explains their symptoms and causes of those symptoms.”

The individualistic approach, a strong aspect of American life and of Western culture in general, he said, stresses that people need to take responsibility for their own behavior. It often neglects, however, a cultural background that encourages reliance on family and friends. If psychiatrists fail to ask about cultural issues, he said, their work is incomplete.

Growing up in Arequipa, Peru, Alarcón credits his parents, both teachers, with spurring his interest in interpersonal relationships and medicine. On Alarcón’s 11th birthday, his father gave him a book on psychology by Honorio Delgado, M.D., also a native of Arequipa, and a leader of Latin American psychiatry. Delgado, who died in 1969, later became one of Alarcón’s mentors.

Alarcón now holds the Honorio Delgado Chair at the Universidad Perúana Cayetano Heredia School of Medicine in Lima, Peru, from which he graduated in 1965.

Alarcón received APA’s Simón Bolivar Award and George Tarjan Award. He also is an APA distinguished life fellow.

The author or coauthor of over 250 articles, 15 books, and 70 book chapters, Alarcón is the senior editor of Psiquiatría (Psychiatry), the most widely used psychiatric textbook in Latin America. This 1,000-page textbook includes chapters from nearly 300 contributors from Latin and Central America, Brazil, Spain, and the United States. The fourth edition of the book, sponsored by the Pan American Health Organization, is scheduled for publication in 2017. ■