Number of Seniors Who Are Prescribed Multiple Psychotropics Rising Fast

Abstract

Physician visits involving three or more drugs of the central nervous system has doubled since 2004, with especially large increases among seniors who are women and live in rural areas.

From 2004 to 2013 the number of U.S. seniors taking three or more psychotropic medications more than doubled—an uptick that does not appear to have been driven by trips to a psychiatrist’s office, according to report published February 13 in JAMA Internal Medicine.

Donovan Maust, M.D., hopes that more psychiatrist involvement in collaborative care programs will help stem the over-prescribing of psychotropic drugs to seniors.

Donovan Maust, M.D., a geriatric psychiatrist at the University of Michigan Medical School in Ann Arbor, and colleagues analyzed data on patients 65 and older. The data were collected as part of the National Ambulatory Medical Care Survey (NAMCS), an annual survey of office-based physicians.

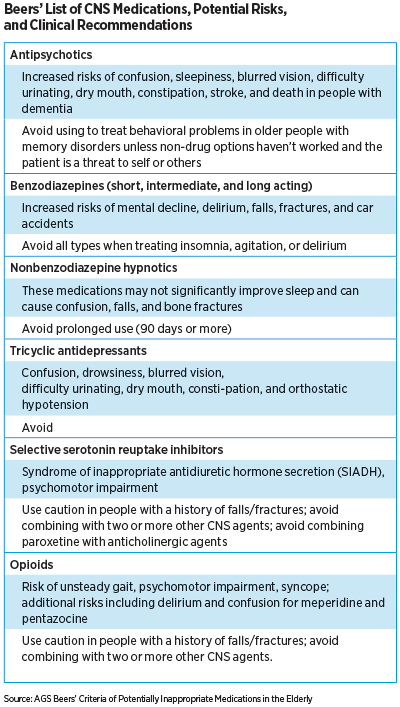

Specifically, the researchers wanted to know the number of patients who started or continued taking the following medications: antipsychotics, benzodiazepines, nonbenzodiazepine hypnotics, tricyclic antidepressants, selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors, and opioids. These medications all appear on the Beers Criteria—a list compiled by the American Geriatrics Society highlighting medications that may pose a risk to older adults (see chart).

Based on the study’s assessment, annual visits by seniors in which three or more psychotropic medications were initiated and/or continued rose from 0.6 percent in 2004 to 1.4 percent in 2013. This translates to 3.68 million doctor’s visits nationally involving seniors in 2013. Over 90 percent of these visits were conducted outside the psychiatric setting.

“What we found most concerning about these numbers is that nearly half of these visits did not include a diagnosis for a mental health or pain disorder,” Maust told Psychiatric News. “This begs the question of why physicians are exposing patients to all the risks of these medications, but not for the diagnoses they are intended to treat.”

One possibility is that older patients more commonly display symptoms like loneliness that may not be captured by a standard diagnostic questionnaire, he explained. Therefore, while the patients may fail to meet the strict clinical definition of depression, their elevated levels of emotional distress might prompt clinicians to prescribe an antidepressant.

However, another study by Maust and his colleagues published in January in Psychiatric Services suggests the rise in prescriptions may not be due to clinicians misinterpreting symptoms of distress. The group assessed a cohort of older adults who were participating in a clinical study on medication adherence; all the participants were enrolled based on having received a new antidepressant prescription, but further testing showed that not everyone in the study had depression. Maust and his colleagues compared the participants and found that the newly prescribed people without a clinical diagnosis of depression scored much higher on assessments of emotional well-being than people with depression.

Another explanation for the rise in the number of seniors on psychotropics may be that seniors today may be more comfortable discussing any temporary mood changes they have experienced with their physician. Primary care providers—who provide the majority of care to seniors and may have little experience treating mental health needs in older patients—may be more inclined to prescribe antidepressants as a precaution, Maust explained.

“About 20 years ago, we were all talking about the undertreatment of mental illness in older adults, so it’s progress to see older patients more open to discussing mental health issues with their doctors,” he said.

Still, the risks associated with psychotropic and polypharmacy use in older adults should be on the radar of all physicians. Maust said he is hopeful that as more efforts are made to connect primary care physicians with psychiatrists, primary care physicians will become more familiar with best practices for prescribing psychotropics to older adults.

“Psychiatrists should always be asking what we can do as a profession to help out primary care providers,” he said.

Maust’s studies were supported by grants from the National Institute on Aging, American Federation for Aging Research, The John A. Hartford Foundation, and the Atlantic Philanthropies. ■