Researchers Dig Into the ‘How’ and ‘Why’ of Device Use by People With SMI

Abstract

Technology can be a powerful therapeutic tool for people with schizophrenia and related disorders, but understanding the nuances of how these patients use digital media is critical.

For people who have severe mental illness (SMI) that impairs normal functioning, digital tools like smartphones can help patients overcome barriers such as lack of access to mental care and social withdrawal.

However, getting the right digital tools into the hands of these patients requires a good understanding of how people with SMI use these devices. There is good evidence that people with SMI have access to technology and are generally not averse to using it, but that doesn’t tell the whole story about patient engagement with phones, computers, and other devices.

A few months back, the National Alliance on Mental Illness (NAMI) partnered with the Harris Poll to conduct an online survey among people with a schizophrenia spectrum disorder about their digital habits.

With 457 participants, the study was the largest on technology used by people with schizophrenia to date, and it provided some revealing data. However, as an online survey, the findings are biased toward people who already have some digital access.

“The survey showed us that not only are these patients familiar with technology, they are actively owning it; they are part of the digital community,” said John Torous, M.D., the co-director of the Digital Psychiatry Program at Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center and Harvard Medical School and one of the investigators involved with the NAMI survey.

Indeed, almost all the respondents had access to at least one technological item (personal or public computer, tablet, smartphone, regular mobile phone, or landline), while 60 percent had access to two or more, and 30 percent had four or more—a prevalence equivalent to the general population.

“This helps dispel the notion of a digital divide between people with and without an SMI,” he continued.

If anything, the study revealed that over-exposure to technology and potential addiction might be more pressing concerns in this patient population than fears of being underconnected. Among participants with access to a computer, for example, around 18 percent spent 10 or more hours a day on that device, while 14 percent of participants with a smartphone used that device at least 10 hours a day.

The way SMI patients used these devices also aligned with that of the general population: web surfing, visiting social networks, and playing games were the most common activities. Some of this digital activity was related to managing their illness, such as scheduling appointments or monitoring symptoms. Nonetheless, Torous noted that 40 percent of the respondents used technology rarely or never to cope with their illness.

“Studies like this are needed so we can get a better sense of what people with SMI find helpful and not helpful,” said Torous. “This way we can avoid developing tools that patients won’t end up using.”

Unexpected Management Avenues Uncovered

Torous acknowledged that the survey was a just a first step that provided a broad census of how people with SMI use technology in everyday life, but it does lead the way for more focused follow-up studies.

For example, one of the more interesting items in the survey results revealed the extent to which music is used in the management of schizophrenia. More respondents (42 percent) listened to music or other audio to manage voice hallucinations in their head compared with trying to gain mental health information (38 percent) or managing their medications (28 percent).

Torous and colleagues at Harvard are now conducting their own survey with patients to learn more about the role of music in the management of their illness, such as what genres work well. The goal is to develop a therapeutic audio app.

“These people are finding their own ways to make technology work for them,” Torous told Psychiatric News. “In some ways, they are a little ahead of us researchers.”

Technology Helps After Hospital Discharge

Dror Ben-Zeev, Ph.D., professor of psychiatry and director of the mHealth for Mental Health Program at the University of Washington, is another advocate for employing technology in mental health care. And as with the NAMI survey, findings from the many focus groups and community surveys he has carried out have also defied some preconceptions about digital devices and people with SMI.

“There may be some motivational barriers that people with SMI have to overcome when using devices, but overall we can confidently state that when digital health resources are designed appropriately, symptoms like persecutory thoughts or low literacy are not barriers to engagement,” he said.

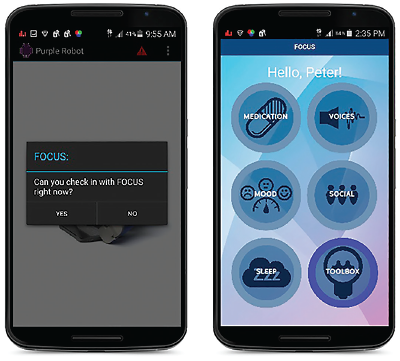

In fact, research by Ben-Zeev and colleagues with a mobile application known as FOCUS has found that people with SMI can engage with technology even during one of the most high-risk periods—immediately after hospital discharge. The FOCUS app provides brief, interactive exchanges centered on five key areas: medication use, mood regulation, sleep, social functioning, and coping with auditory hallucinations.

Among recently discharged patients who were given the FOCUS app as part of a multi-component technology assisted relapse prevention program, around 73 percent used it regularly for at least three months, and nearly half used it for at least five months. Ben-Zeev is wrapping up a related randomized trial that is comparing the efficacy of FOCUS in improving the symptoms of SMI when compared with in-person group therapy.

While he is awaiting the final data, Ben-Zeev is confident that FOCUS will prove quite useful in getting skills and information to patients. “When we look at traditional clinic-based services, it seems that a sizeable number of participants don’t make it to the sessions, and you cannot get exposed to the intervention if you’re not in the room,” he told Psychiatric News.

In addition to higher levels of engagement, apps like FOCUS may require lower costs. Once a working version is developed, FOCUS requires occasional updating and money for support staff. As Ben-Zeev pointed out, though, in his comparative effectiveness study he needs only one support person to manage all the participants, largely remotely. By comparison, his in-person sessions require two facilitators for each group, as well as patient transportation and clinic space.

“Looking ahead, I think it’s time to expand our boundaries and go beyond the patients who have been in the ‘services world’ for a decade or more,” he said. “With these digital tools, we might be able to intervene earlier on, and that’s why it’s important to gain knowledge about how people at-risk for illness are using technology in the real world.”

Beyond that, Ben-Zeev believes that studies like the NAMI survey offer another important message.

“Many people still think of schizophrenia patients as this monolithic community, and that is not the case,” he said. “We categorize these individuals for clinical reasons, but just as they vary in technology usage, they vary in all other aspects of life. Under this umbrella label, you have patients who have major difficulty with employment, but on the other end, you also have highly accomplished professionals. That’s just one example of the range we see in people seeking care.

“If we want to succeed, we need to think of these folks in a more nuanced, personalized way.” ■

“Digital Technology Use Among Individuals With Schizophrenia: Results of an Online Survey” can be accessed here.