Percentage of Americans Taking Antidepressants Climbs

Abstract

One contributing factor to the growth of patients taking antidepressants may be that they are being prescribed the medications for non-depression diagnoses, such as anxiety, sleep, and neuropathic pain.

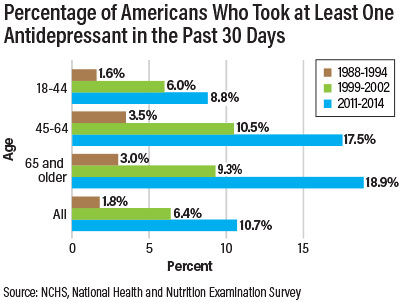

Between 2011 and 2014, approximately one in nine Americans of all ages reported taking at least one antidepressant medication in the past month, according to national survey data released by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Three decades ago, less than one in 50 people did.

The use of antidepressants increased with age and reached nearly 19 percent in adults 65 years and older (see bar chart). From 1988 to 1994, only 3 percent of older adults were taking antidepressants.

The data were collected in the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) by the CDC.

The sharp rise of antidepressants in all age groups, except children and adolescents, followed the introduction of the first selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor (SSRI), fluoxetine (Prozac). Prozac was first approved in the United States in 1987 and entered the market in 1988. Since then, many more SSRIs and other types of antidepressants have become available. The rise of direct-to-consumer marketing since the 1990s further pushed antidepressants into the public consciousness.

Because SSRIs do not carry the potentially life-threatening cardiac risks associated with tricyclic antidepressants, they are considered safer and easy to manage, particularly for elderly patients who often have coexisting cardiovascular diseases.

While the current prevalence of antidepressant use in older people is more than twice of that in adults under 45, this does not mean older people are more likely to have depressive disorders. Epidemiological research has shown that depression is not more common in older adults than in younger adults and antidepressants tend to be less efficacious for older patients.

One reason contributing to the popularity of antidepressants is the expansion of their indications. “Many patients are given antidepressants for non-depression diagnoses, such as anxiety, sleep, and neuropathic pain,” Donovan Maust, M.D., M.S., a geriatric psychiatrist and assistant professor of psychiatry at the University of Michigan, told Psychiatric News.

Since older adults tend to have more contact with the health care system than younger adults, they may be more likely to be given an antidepressant prescription by their family physician, internist, or other specialist.

“There has been more recognition and awareness of major depression, along with more willingness to prescribe drug therapy,” Maust added. The increase in antidepressants is, therefore, partially justified, he stated.

Overtreatment with antidepressants remains a concern, as geriatric patients are far more likely to suffer side effects and drug interactions from the many more medications they take than younger adults.

“[SSRIs] may be safer than tricyclics, but they still have side effects, particularly in older patients, such as hyponatremia and risk of falling. Meanwhile, there is limited evidence to support their effectiveness for [treating] subsyndromal depression,” said Maust.

For example, antidepressants are frequently prescribed to older patients with dementia to treat mood symptoms, but there is no solid evidence that they are effective for this purpose.

Rather than immediately reaching for the prescription pad, physicians should first clearly establish the diagnosis that may require an antidepressant and plan to measure and monitor the effectiveness, Maust recommended. “Such prescriptions are often motivated by the [physician’s] desire to help patients, especially when resources for psychosocial intervention are not available.” Even without psychosocial resources, however, watchful waiting by scheduling an early return visit may be enough for some patients and help reduce unnecessary prescribing, he suggested. ■