Youths Describe Obstacles On Their Road to Recovery

Listen to us. Don’t talk down to us. Make us a part of the healing process, and give us choices in our treatment.

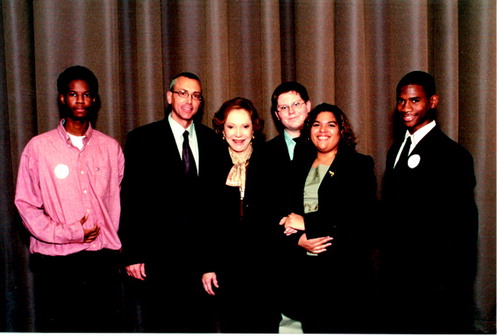

This was just some of the heartfelt advice given by a group of young people with mental illness to 200 attendees who gathered at the 17th Annual Rosalynn Carter Symposium on Mental Health Policy held last month in Atlanta. Psychiatrists, psychologists, mental health and educational administrators, parents, and mental health advocates were among those who attended the symposium.

This was just some of the heartfelt advice given by a group of young people with mental illness to 200 attendees who gathered at the 17th Annual Rosalynn Carter Symposium on Mental Health Policy held last month in Atlanta. Psychiatrists, psychologists, mental health and educational administrators, parents, and mental health advocates were among those who attended the symposium.

As they sat onstage facing 200 attendees at the symposium, “Youth in Crisis—Uniting for Action,” the youths related eerily similar stories of alienation, being bullied, powerlessness, repeated suicide attempts, and an endless parade of doctors, therapists, and medications.

Looking back, the young advocates talked about what best helped them cope. They related their hard-learned lessons to a receptive audience, who had gathered to exchange ideas on how to improve mental health care for children and adolescents.

‘Personal Punching Bag’

“By the time I was in the sixth grade, I had been on at least 20 different medications and had seen at least 10 different doctors,” said Brandon Fletcher. The 15-year-old Nebraskan said that he had been diagnosed with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), bipolar disorder, and an anxiety disorder and had endured years of teasing and frustration from his classmates.

“Most of the time in school, kids teased me,” said Fletcher. “I became their personal punching bag, and I would tell my teachers and the school counselor about [the bullying], but they didn’t believe me and took the other side.”

Fletcher said that each time he got in trouble at school, school authorities told his mother that something must be wrong at home and that she should call Fletcher’s psychiatrist to ask that his medications be increased.

“One time I was on so much medication that I had a seizure in school and had to go to the hospital,” he recalled.

Fletcher said he bottled up his anger and frustration and eventually attempted suicide at home, but his mother found him in time to save his life.

Dally Sanchez, a 21-year-old New York advocate with mental illness, recounted similar tribulations. Sanchez was brought into the mental health system at the age of 12 when she landed in the hospital and was diagnosed with bipolar disorder.

“That started a series of hospitalizations for the next six to seven years,” said Sanchez. “In school, I had problems with my classmates making fun of me and pushing me around. I had to fight a lot to defend myself.”

Sanchez said she repeatedly attempted suicide and was hospitalized each time. This meant that Sanchez continually saw new psychiatrists and therapists, many of whom had different ideas about what was best for her. “There was no continuity as far as my treatment professionals were concerned,” she said.

Another problem Sanchez encountered was poor patient education. She said that none of the people who treated her properly explained to her what having bipolar disorder really meant.

“Only two years ago did I learn that bipolar disorder is much more than just mood swings and depression,” she said.

There were other communication barriers for Sanchez. Since her mother was from the Dominican Republic and spoke little English, Sanchez was asked to translate between the treatment professionals and her mother.

‘Keeping It Real’

Sanchez advised mental health professionals to “talk real” to kids, that is, to use terms that they can understand. “Don’t talk down to youth, but instead talk to them as people who are active and involved in their treatment,” she said. “That will affect how I respond to you.”

After Will Henry of Tampa, Fla., was diagnosed with ADHD, he became involved with a peer group for young people with emotional and behavioral problems. He found that other youngsters opened up to him when he talked to them on their level.

“I call it ‘keeping it real’. . . . It really helped the kids come out of their shells,” said Henry.

Finding Inspiration, Solutions

Just as certain themes emerged in the youths’ stories about the difficulties of growing up with mental illness, other themes came to the forefront in discussion about recovery. One of them was spirituality.

“I know you want to hear about what has helped me,” said Fletcher. “I have seen lots of doctors and counselors and have taken lots of medication, but what has helped me most is finding my faith in God.”

Although Fletcher noted that it helped to find mental health professionals who understood his illness and were willing to listen to him, he advised the audience to “please remember that for some of us, our faith is a valuable tool in helping us get better.”

All of the panelists said that being an advocate and having peer support had contributed significantly to their improved mental health.

Fletcher has been working to start a peer group called Youth Encouraging Support to help other youth with mental illness to learn how to help themselves and to support one another.

“I have been able to travel to conferences and speak to others about illness and have found other kids who have problems just like mine,” said Fletcher, who won the National Mental Health Association’s Medal of Excellence last summer for raising awareness about mental illness in young people.

What most helped Sanchez was a program that provided her with “wraparound services,” which are intensive, community-based mental health services designed to meet the needs of children and adolescents with mental illness and their families on an individual basis.

“For the first time, people were asking me what I needed. I was given choices. . . . I wasn’t just a 15-year-old with bipolar disorder.”

She joined a peer-led program called Youth Forum, which provides peer support, recreation, peer advocacy, and support groups to teens and young adults involved in the mental health system and juvenile justice system.

There, she started to learn to trust adults. “Youth Forum really encouraged me in the things I wanted to do,” she said.

Terrell Williams became involved in advocacy through a program called Children Overcoming Problems Everyday (COPE), a Birmingham, Ala., community-based counseling and outreach program for adolescents and families. Williams is president of the Youth Millennium 2000 group, which encourages young people with mental health problems to achieve as much as possible and invites speakers to address topics such as youth leadership, cultural-competency training, and community service.

“We should be treated as individuals, not as a group or disorder,” Fletcher told the symposium attendees. “Each of us is different, and our treatment should be different.”

Williams said, “I hope you gain knowledge from our experiences,” and he asked mental health practitioners to do the following for the children and adolescents with whom they work: “Value youth; don’t just tolerate them. Embrace them; don’t ignore them. Develop the positive without emphasizing the negative. Include youth; don’t exclude them. Empower them; don’t hold them down.” ▪