Study Finds Link Between Life Satisfaction, Suicide Risk

Life dissatisfaction, not surprisingly, has been associated with symptoms of depression, and depression in turn is known to be a strong suicide risk factor. So might life dissatisfaction per se be a suicide predictor?

The answer appears to be yes, according to a study conducted by a team of Finnish investigators and reported in the March American Journal of Psychiatry.

Back in 1975 Heli Koivumaa-Honkanen, M.D., Ph.D., of Kuopio University Hospital in Kuopio, Finland, and colleagues sent a questionnaire to some 30,000 Finns who were part of the Finnish Twin Cohort Study and who were between 18 years and 64 years of age. The questionnaire dealt with psychosocial factors, health-related factors, and life satisfaction. Questions about life satisfaction covered four items: interest in life, happiness, general ease of living, and feelings of loneliness. Respondents could obtain a score from 4 to 20, with higher scores indicating greater dissatisfaction.

Some 29,000 of the 30,000 Finns returned the questionnaire. Of the 29,000 subjects, 19 percent reported that they were satisfied with their lives (that is, received a score of 4 to 6 on the questionnaire); 18 percent reported that they were not (that is, received a score of 12 to 20 on the questionnaire); and the rest reported that their life satisfaction lay somewhere between the two extremes.

The investigators then followed the fates of the 29,000 subjects over the next two decades—from 1976 to 1996.

Of the 29,000 subjects, 182 committed suicide at some point during those years, the researchers found. Those who killed themselves were more likely to be men than women (149 versus 33), more likely living alone than with a partner, more likely to be smokers than not, and more likely to be heavy alcohol users than not. And, the researchers discovered, they were far more likely to have reported in 1975 being dissatisfied with their lives than were those subjects who did not commit suicide.

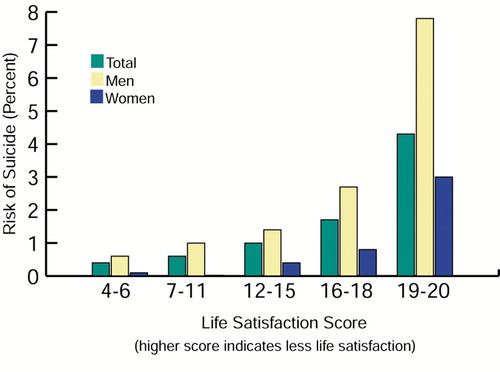

What’s more, there appeared to be a dose-response relationship between dissatisfaction and later suicide (see chart). For instance, those men who had been most dissatisfied with their lives back in 1975 (that is, those who had scored between 19 and 20 on the questionnaire) turned out to be 25 times more at risk for committing suicide during the subsequent decade than were men who had been happy with their lives in 1975. And even a decade later, from 1986 to 1996, those men who had been most dissatisfied in 1975 were still more at risk of suicide than were those men who had been satisfied in 1975.

Thus, “life dissatisfaction has a long-term effect on the risk of suicide,” the researchers concluded.

But why are certain people dissatisfied? Poor health can probably explain some cases. Those men who had been both dissatisfied and sick in 1975 turned out to be at a higher risk of suicide later than those men who had been dissatisfied but healthy in 1975, the Finnish researchers found. In contrast, poor health probably doesn’t explain all cases of dissatisfaction and the suicide that may result from it, because when the Finnish investigators took the health of their subjects into consideration, they still found a strong link between dissatisfaction and subsequent suicide danger.

So if poor health cannot always explain life dissatisfaction and the suicide risk that may result from it, what are some other possible explanations? One may simply be personality, or a person’s outlook on life, the Finnish scientists suspect. For instance, a study reported by other researchers back in 1994 found that men who are hostile are especially susceptible to suicide.

In any event, regardless of why some people are satisfied with their lives and others are not, the Finnish researchers believe that their results have some practical implications. “Undiagnosed depression is one of the main obstacles to suicide prevention,” they write. [Thus] the assessment of life satisfaction could, in part, promote the early identification of depressive persons who have not necessarily been in reach of psychiatric evaluation.”

The study, “Life Satisfaction and Suicide: A 20-Year Follow-Up Study,” is posted on the Web at ajp.psychiatryonline.org/cgi/content/full/158/3/433. ▪