Stereotypes Still Keep Women From Academic Achievement

When women psychiatrists are not considered for leadership positions for which they are qualified, they often hear such comments as “I didn’t think your husband would be willing to move” or “I heard that you had several children, so I didn’t think you could take on this new responsibility,” according to Leah Dickstein, M.D., a professor of psychiatry at the University of Louisville School of Medicine and associate dean for faculty and student advocacy.

Women faculty over the age of 50 may also face age bias, said Dickstein at APA’s 2002 annual meeting in May in Philadelphia. “We are viewed as too old and over the hill to assume new leadership responsibilities. Yet men in academic medicine in their 60s and 70s are offered new positions as deans, department chairs, and presidents of academic institutions and senior academic leadership opportunities.”

The session was sponsored by the Association of Women Psychiatrists (AWP), of which Dickstein is a former president.

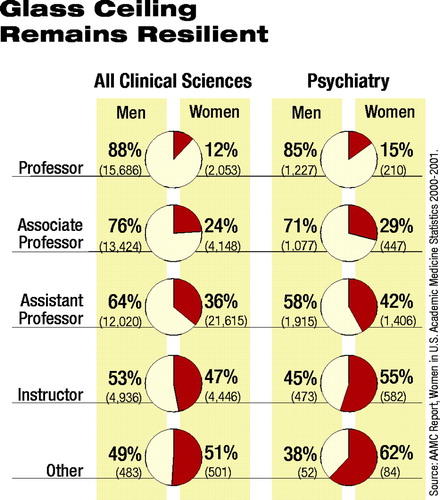

Gender-biased assumptions combined with lower salaries, lack of mentoring or effective mentoring, and more clinical and teaching assignments than their male colleagues receive add up to frustration for women attempting to advance their careers, said Dickstein. These barriers have kept the number of women full, associate, and assistant professors low compared with men professors (see chart).

Gender-biased assumptions combined with lower salaries, lack of mentoring or effective mentoring, and more clinical and teaching assignments than their male colleagues receive add up to frustration for women attempting to advance their careers, said Dickstein. These barriers have kept the number of women full, associate, and assistant professors low compared with men professors (see chart).

Of the nation’s 125 medical schools, only five have permanent deans who are women physicians, and none is a psychiatrist. Women make up 8 percent (206) of all permanent department chairs, and only five are psychiatrists.

Studies on salaries and gender in academic medicine have found that women in some specialties and at some institutions earn up to 30 percent less than their male counterparts, said Bickel.

Dickstein blamed women’s lack of progress in academic medicine on “too many stereotypes and a lack of courage on the part of our male colleagues to mentor and recommend qualified women for leadership positions.”

The dearth of women faculty in the top ranks means fewer role models, mentors, and networking opportunities for other women physicians, said Dickstein.

Mentors can provide valuable information about promotion criteria, networking, and salaries. However, mentors tend to advise men about promotion criteria without being asked more than they do women, said Carol Nadelson, M.D., director of the Office of Women’s Careers at Brigham and Women’s Hospital, an affiliate of Harvard Medical School. Nadelson was the first woman president of APA.

Women, especially those with children, sometimes feel so grateful when they are offered an academic position that they don’t think about negotiating salaries or research time, space, and support staff, said Janet Bickel, AAMC associate vice president for medical school affairs.

Rules for Advancement

The rules for promotion in academic medicine were developed by men. Thus, it is not surprising that women in academia sometimes feel like a square peg trying to fit into a round hole.

For example, promotion and tenure committees measure outstanding performance by the number of papers published in peer-reviewed journals. The problem with this yardstick is that women in nonsurgical specialties may be assigned more clinical duties and more complex patients than their male colleagues, said Bickel. This leaves women with less “protected time” to conduct research and write papers.

Marion Goldstein, M.D., an assistant professor and director of the division of geriatric psychiatry at the State University of New York at Buffalo, recalled a painful lesson she learned during her research career. She said that her NIH grant wasn’t renewed because she didn’t have time to publish several papers.

“I was directing an 18-bed geriatric inpatient unit, teaching residents, and rotating coverage for five other psychiatrists,” said Goldstein.

Dickstein would like the academic promotion criteria changed to reflect women’s strengths. “There should be less emphasis on research qualifications for leadership positions, with the exception of vice deans or chairs of research, and more emphasis on excellence in administration, education, and fostering faculty, resident, and student development,” said Dickstein.

Women with fewer published research papers than their male colleagues often have larger citation indexes and write more comprehensive papers, said Nadelson. Promotion committees, however, often ignore those factors, she observed.

Women in the workplace often receive mixed messages about how they are expected to behave. Altha Stewart, M.D., gave some examples: “Take risks, but don’t make mistakes, and be consistently outstanding.” “Be tough but be feminine.” “Be ambitious but don’t expect equal treatment.” Stewart is a consultant with the Physicians Group at Wayne State University in Detroit and chairs the APA Council on Psychiatric Services.

More Assertiveness Needed

Nadelson said a common problem among women in medicine is they have trouble asserting and promoting themselves. “This often leads to not exercising their authority or doing it awkwardly.”

Leah Dickstein, M.D. (right), presents the 2001 Alexandra Symonds Award to Ann Turkel, M.D., an assistant clinical professor of psychiatry at Columbia University College of Physicians and Surgeons and president-elect of the American Academy of Psychoanalysis, at APA’s 2002 annual meeting.

Many women who don’t see themselves as powerful end up feeling that they are inadequate, even “imposters.”

“This self-devaluation leads to the belief that success is due to luck or chance rather than ability,” said Turkel, an assistant clinical professor of psychiatry at Columbia University College of Physicians and Surgeons.

She noted that women who are direct and straightforward risk being called “bitchy” and “tough,” whereas the same traits in men are perceived as strengths.

Turkel argued that women can be successful leaders without copying traits associated with male leadership, such as being controlling, analytical, or unemotional. “Feminine traits of leadership emphasize collaboration, cooperation, empowerment of others, and problem-solving skills based on intuition, empathy, and rationality,” she said.

Women leaders, however, often struggle with risk taking because they have not been taught through competitive play or sports—as men have—to see risks as gains or losses but only as danger or loss, said Turkel.

Dickstein recommended reading Walking Out on the Boys by Frances Conley, M.D., a neurosurgeon at Stanford University who publicly charged the school with sexual harassment and resigned as chair of the neurosurgery department to protest the promotion of a male colleague. Also recommended was the self-help book Hardball for Women: Winning at the Game of Business by Pat Heim, Ph.D., and Susan Golant.

The executive summary of the 2002 “Report on Increasing Women’s Leadership in Academic Medicine: Project Implementation Committee” is posted at the AAMC Women in Medicine Web site at www.aamc.org/members/wim/iwl.pdf. ▪