SSRIs Show Little Difference As First-Line Treatment

At a time when pharmaceutical companies are engaged in an escalating marketing campaign to distinguish their antidepressant medication from all the rest (see story on page 9), a new large and comprehensive study has concluded that the three best-selling selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) are nearly indistinguishable as first-line treatments of depression in primary care.

In an attempt to study the effectiveness of SSRIs in the setting in which the vast majority of them are prescribed, a large group of primary care physicians conducted a clinical trial of fluoxetine (Prozac), paroxetine (Paxil), and sertraline (Zoloft) to look for differences in effectiveness, safety, and side-effect profile. The study’s results appear in the December 19, 2001, Journal of the American Medical Association.

The outcome appears to have surprised the primary care physicians and, one would imagine, troubled pharmaceutical-industry marketing executives.

The irony is that the study was funded by a grant from Eli Lilly and Company, maker of Prozac, one of the three SSRIs being evaluated. Lilly did not exert any influence over the research, despite the possibility that results might not have been favorable to its product, according to sources.

Kurt Kroenke, M.D., a primary care specialist and researcher at the Regenstrief Institute for Health Care in Indianapolis, led a group of collaborators at 37 clinics within two primary care research networks in the United States. The primary care physicians enrolled 601 patients, of whom 573 completed the study. The group compared the effectiveness of the three SSRIs in an open-label, randomized, intention-to-treat study that would closely mirror the conditions of depression diagnosis and medication treatment in primary care settings.

“This study was very appropriate from the standpoint that [primary care] is where the action is,” John Greden, M.D., Rachel Upjohn professor and chair of psychiatry and clinical neurosciences at the University of Michigan, told Psychiatric News. “If we don’t look at it there, then we are missing a great deal—[psychiatrists] are not seeing people until they are much worse, in the later stages of depression.”

The study was designed to resemble real-world practice in that the decision to initiate antidepressant treatment was based solely on the primary care physicians’ (PCP) judgment that there was clinical depression present that warranted treatment with medication. It did not require that criteria for specific diagnoses, such as dysthymia or major depression, be proven.

Both the PCP and the patient knew that all subjects would receive one of the three active SSRI medications; however, neither knew which drug the patient was randomized to nor the milligram strength of the drug (relative strengths such as “low dose” or “moderate dose” were used).

The physician was free to adjust dosing or change to one of the other two antidepressants based on his or her judgment of clinical response; however, medication was intended to be continued for the entire nine months of the trial.

The investigators used the Medical Outcomes Study 36-Item Short Form Health Survey (SF-36) Mental Component Summary (MSC) as the primary measure of depression. Secondary measures included two SF-36 subscales that correlate highly with depression, a modified subscale of the Hopkins Symptom Checklist and Brief Symptom Inventory, and the Primary Care Evaluation of Mental Disorders (PRIME-MD), which was used to correlate retrospectively patients’ symptoms with DSM-IV criteria as well as to qualify diagnostic subgroups.

Greden, chair of APA’s Council on Research, noted that he would have preferred to see “a real measure of depression severity used, such as the Hamilton Depression Rating Scale or the Beck Depression Inventory.”

DSM-IV criteria for major depression were met in 74 percent of the sample at baseline, the researchers found, while 18 percent met the criteria for dysthymia and the remaining 8 percent for minor depression.

“The data clearly speak for themselves,” said Greden, who directs the University of Michigan’s Depression Center. “And they did find that all three medications had the same onset, the same amount of effectiveness, and the same adverse-event profile.”

After three months on one of the medications, the proportion of patients in the entire sample meeting criteria for major depression dropped to 32 percent from 74 percent at the beginning of the study. By nine months, only 26 percent met the criteria for major depression.

It is important to note that the study protocol did not include any provision for providing psychotherapy. “That is certainly consistent with the care delivered in such settings,” Greden noted, adding that with the constraints on time and resources within primary care, psychotherapy is rarely conducted.

“But the fight between psychotherapy and medication has been fought most vigorously within psychiatry itself, not in primary care,” Greden added. For people with chronic depression, he said, the data are clear that the most effective treatment includes both therapy and medication.

“But this study does illustrate that in a primary care setting, you can make a significant difference in depression.”

No statistically significant differences were reported for any of the outcome measures between the three SSRIs.

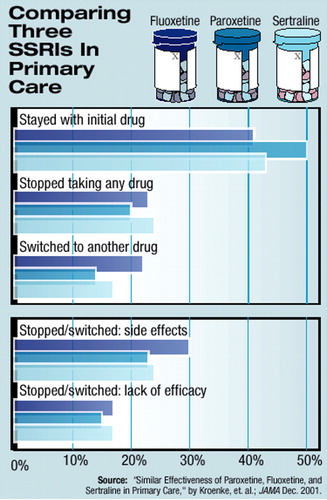

In addition, the number of subjects who continued to take the drug to which they were initially randomized for the duration of the nine-month trial was around half for each of the three drugs studied. The proportion of patients who stopped taking any of the SSRIs or who switched to another drug steadily increased over the nine months, from 13 percent at one month to over 40 percent at nine months (see chart). Again, however, no significant difference was seen among the three SSRIs when switching or stopping the medication was assessed.

In addition, the number of subjects who continued to take the drug to which they were initially randomized for the duration of the nine-month trial was around half for each of the three drugs studied. The proportion of patients who stopped taking any of the SSRIs or who switched to another drug steadily increased over the nine months, from 13 percent at one month to over 40 percent at nine months (see chart). Again, however, no significant difference was seen among the three SSRIs when switching or stopping the medication was assessed.

Reported side effects were relatively rare and did not differ by drug.

Cost Implications of Findings

The study demonstrates, wrote the authors, that “these three SSRIs do not differ across a wide array of psychological, social, work, and other health-related, quality-of-life domains in either the magnitude or the time course of response.”

They note that with generic SSRIs now becoming available, the results have “important implications for health care costs.”

While not all SSRIs are created equal, they concluded that “none of the three SSRIs in this study can be recommended over another in terms of effectiveness.”

In an editorial accompanying the article, Gregory Simon, M.D., M.P.H., a research assistant professor of psychiatry at the University of Washington, noted that “the fact that SSRI drugs are equally effective on average does not mean that they are equally effective for individual patients.”

Simon argued that the results of the primary care study may lend credence to the push to use drug formularies to restrict prescribing options to the lowest-cost SSRI. However, he cautioned that physicians must retain the flexibility to be able to switch a patient to another drug when the lowest-cost choice is not successful.

The Take-Home Message

Greden said he was not surprised by the robustness of the response in a patient cohort in which nearly three-fourths of the subjects met the criteria for a DSM-IV diagnosis of acute major depression at the start of treatment.

“This was a primary care setting,” he said. “That means that you are catching the disorder earlier in its life, when it is best treated and most responsive.”

Greden said the study certainly confirms that good results are possible in treating depression in primary care settings.

“And this is the message of the study that needs to be emphasized. What really counts is earlier detection, earlier intervention, and prevention of recurrences.”

An abstract of the study, with a link to the editorial, is posted online at http://jama.ama-assn.org/issues/v286n23/abs/joc10747.html. ▪