Distinction Between Mood, Affect Eludes Many Residents

Mood or affect: that is the question. Not all psychiatry residents know the answer. More precisely, many have an incomplete understanding of the temporal aspects of these fundamental psychiatric concepts, according to the results of a small survey of 99 residents reported in the August American Journal of Psychiatry.

These inconsistencies may reflect the differing definitions that appear in the literature and standard psychiatric texts, as well as the varied understanding of the concepts by educators and the wider psychiatric field. Such inconsistencies can lead to a tendency to simplify approaches to the mental status examination, according to Michael Serby, M.D.

Specifically, he said, confusion about these terms can result in an overly literal approach to the interview, with the physician’s taking at face value the verbal responses of a patient while ignoring the more subtle nuances of unstated feeling.

Serby is associate chair of psychiatry at Beth Israel Medical Center in New York and a professor of clinical psychiatry at Albert Einstein College of Medicine.

He said that there are two dimensions along which to understand mood and affect: the temporal dimension, in which mood is sustained, and affect is transient; and the subjective/internal versus objective/external dimension, in which mood is viewed as internal and affect as external.

A complete understanding of the concepts, then, would synthesize the two: mood is sustained and internal, while affect is momentary and external.

Serby said his observation of residents performing the mental status exam revealed a tendency to give short shrift to the temporal dimension of mood.

“Over the years, I have taught residents and medical students about the mental status examination,” Serby told Psychiatric News. “I noted in looking at workups and notes and presentations that when they approach the exam, they usually defined affect and mood in what I felt to be simplistic ways.”

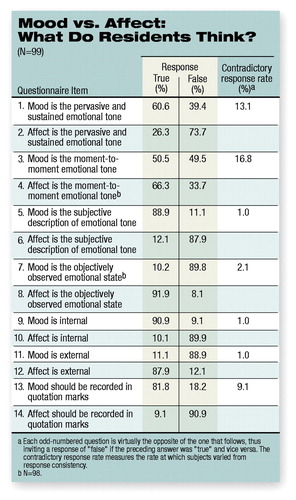

The survey appears to have borne out his observations. In the survey, 99 trainees in residency programs in New York City were given a 14-item true-false questionnaire (see table). Because some of the questions were the opposite of a previous question (inviting “false” if the previous answer was “true”), it was possible for respondents to give contradictory responses.

The survey appears to have borne out his observations. In the survey, 99 trainees in residency programs in New York City were given a 14-item true-false questionnaire (see table). Because some of the questions were the opposite of a previous question (inviting “false” if the previous answer was “true”), it was possible for respondents to give contradictory responses.

So, for instance, 60.6 percent of the residents said mood was “sustained,” but 50.5 percent also said it was “momentary.” Further, 26.3 percent said affect was “pervasive,” but 66.3 percent said it was “momentary.”

The same confusion did not appear to exist around the internal/external dimension of the two terms. Residents overwhelmingly defined mood as being subjective and internal and affect as being objective and external.

What this all means, Serby said, is that residents are prone to relying on a literal transcription of an interview without paying attention to the full range of stated and unstated feelings.

“I have great concern about relying on this idea that mood is solely internal and subjective,” said Serby. “This results in simply asking the patient what they are feeling, accepting what they say, and recording it. When we see a patient for 30 minutes or an hour, we get a sense of that patient’s emotional state over time. The patient might appear to be joyless and might make numerous negative, bleak statements. But when asked about mood, the patient might say, ‘Fine, O.K.’ ” Often, he continued, the resident reports the patient’s mood as described by the patient, instead of perceiving and reporting the depression as the patient’s overriding feeling.

“As psychiatrists we are supposed to be adept at understanding and sensing the unstated,” Serby said.

Serby said that the inconsistencies likely reflect varying definitions and understandings offered by standard psychiatric texts, as well as by educators and the field at large.

“Residents’ attitudes and approaches reflect not only the current teaching, but also future accepted wisdom,” Serby said. “All psychiatrists should consider the temporal as well as the internal/external and subjective aspects of these terms. I think we will have a richer, fuller sense of our patients, and be able to convey that more fully to our colleagues.” ▪