State Officials Seek Bridge Over Medicaid’s ‘Troubled Waters’

“Navigating Troubled Waters”—the conference’s title clearly set the theme for the 16th Annual State Health Policy Conference in August, hosted by the National Academy for State Health Policy (NACHP) in Portland, Ore.

Nowhere was the importance and difficulty of that challenge more apparent than in the discussions about Medicaid.

In the plenary session, titled “Medicaid’s Reform: Navigating Rapids, Riptides, and Reform,” James Tallon Jr. told the audience, “You can’t think of Medicaid as just a safety net. [That reasoning implies] that something else has failed, but there is no alternative system. Medicaid is the primary health insurer for low-income people and for long-term care.”

He added that private insurers want “nothing to do with people who have disabling conditions.”

Tallon, chair of the Kaiser Commission on Medicaid and the Uninsured, was majority leader in the New York State Assembly from 1987 to 1993 and is president of the United Hospital Fund of New York.

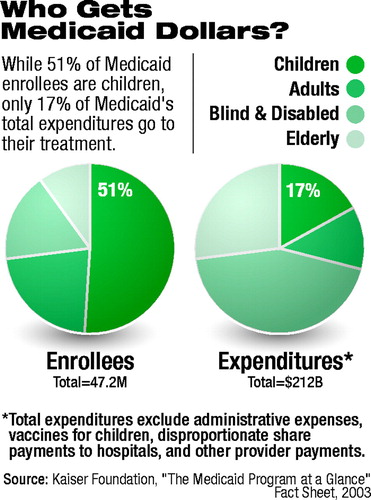

Debbie Chang, M.P.H., NACHP’s director of strategic development and policy, said that Medicaid’s annual budget was $2 billion when it was established in 1965. By 2002, the figure had grown to $212 billion.

She said that historically when there has been a problem, public officials would “go to the Medicaid program to fix it.” By 2001 the program had become the largest source of federal funds for states.

Enrollees who are blind or have other disabilities accounted for 44 percent of expenditures in 2002, although they represented only 17 percent of the enrollees. Children, in contrast, represented 51 percent of enrollees and accounted for only 17 percent of expenditures (see chart).

Enrollees who are blind or have other disabilities accounted for 44 percent of expenditures in 2002, although they represented only 17 percent of the enrollees. Children, in contrast, represented 51 percent of enrollees and accounted for only 17 percent of expenditures (see chart).

Kevin Concannon, director of the Iowa Department of Human Services, called the Medicaid program a “lifesaver,” which had “progressively expanded its responsibilities for the disabled.”

He advised that Medicaid funds and legislative authority be used as leverage to provide benefits for people who do not meet the program’s eligibility standards.

Concannon was commissioner of Maine’s Department of Human Services when that state used such a strategy to develop the landmark program that allows low-income people who are not Medicaid eligible to purchase prescription drugs at prices that reflect Medicaid discounts.

He recently consulted with the 10-member, bipartisan committee of governors who considered reform in light of President George W. Bush’s effort to convert Medicaid into a block-grant program.

The governors agreed that the federal government should become responsible for financing “dual-eligibles,” the more than 6 million people who are eligible for both Medicare and Medicaid, and that the program should be simplified and become more flexible.

Concannon warned against Bush’s proposal. “When people start dangling block grants in front of you,” he said, “take a brief walk down history’s lane.” Accountability, program focus, and funds often have been lost when categorical programs become block grants to states.

Stephen Mayberg, Ph.D., director of the California Department of Mental Health, cited as an example of the need for flexibility the fact that many people with serious mental illness receive Supplemental Security Income. But if they improve and are able to work, they lose Medicaid coverage, which pays for medications and other supports.

Mayberg was a member of Bush’s New Freedom Commission on Mental Health.

Although none of the panelists expected major changes or increased funding for Medicaid in the near future, Tallon urged the audience to take a long-range view of the importance of the discussions about reform.

“It’s really a debate about who pays,” he said. “And that makes it part of the larger debate about federal responsibility [for the poor and the sick].”

Tallon said that Bush’s proposal for Medicaid reform reflects an ideological position that minimizes the role of the federal government in helping those populations.

The proposal, which was presented in January but dropped after complaints from the National Governors Association, would have offered states $12.7 billion in “extra money” over the next seven years, with equivalent reductions in the following years to compensate for that increase.

States would have had increased ability to drop benefits and covered populations and could have been eligible for federal funds with a lower match of state dollars, thus decreasing the total funds available (Psychiatric News, March 7).

“The proposal was an effort to eliminate the federal liability for the rising costs associated with the aging of the baby boomers,” he said. “The debate is about who will pay those costs over the long run.”

Materials presented at the conference are posted on the Web at www.nashp.org. ▪