Community Treatment More Humane, Reduces Criminal-Justice Costs

Keeping people with untreated mental illness locked up in the nation’s prisons and jails is not only inhumane, it is a costly proposition, according to the keynote speaker at APA’s fall component meetings in Washington, D.C., last month (see Original article: facing page).

Due to fiscal constraints, state legislators are likely to respond favorably to economic arguments when asked to back alternative treatments for nonviolent offenders with mental illness.

Due to fiscal constraints, state legislators are likely to respond favorably to economic arguments when asked to back alternative treatments for nonviolent offenders with mental illness.

“Many of you know of my concerns involving the criminalization of the mentally ill,” APA President Marcia Goin, M.D., told members of the Association’s components. “The question is, What can we do to stop it?”

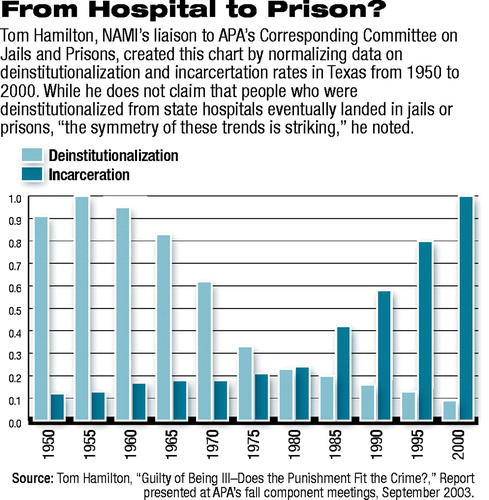

In the way of an answer, she introduced Tom Hamilton, Ph.D., past president of the National Alliance for the Mentally Ill (NAMI) Texas and NAMI liaison to APA’s Corresponding Committee on Jails and Prisons.

When his son was diagnosed with schizophrenia 12 years ago, Hamilton was unprepared for what was to come. “I suddenly realized how ignorant I was of anything having to do with mental illness. . . .I knew nothing about what we’d gotten into or what the impact would be on my son.”

He quickly educated himself, however, and brought 30 years of experience in the business world—part of it as a CEO in the gas and oil industry—to the fight against the criminalization of people with mental illness.

In his professional life, Hamilton said, he was accustomed to making economic decisions based on data “that are less than scientifically pristine,” which suited him well when dealing with the often-conflicting numbers pertaining to the incarceration of people with mental illness.

But one thing was certain: “The U.S. came into the new millennium with the largest incarcerated population in the world,” Hamilton said. According to the U.S. Department of Justice’s Bureau of Justice Statistics, 1 of every 32 adult Americans was either in jail, prison, or on probation in 2000. Furthermore, 16 percent of that number reported having a recurrent mental illness or spending time in a psychiatric hospital.

“I’m convinced this statistic is well understated,” Hamilton said, pointing out that many people with mental illness lack insight into their condition, and stigma keeps others from reporting a mental illness.

Hamilton said that “transinstitutionalization” of people with mental illness resulted when state psychiatric hospitals began discharging great numbers of patients into communities ill prepared to handle them throughout the 1960s and 1970s.

During that period, there was an upward trend in the prison population coinciding with a shift in law enforcement policy in many states from a rehabilitative to a punitive approach.

“I’m not trying to suggest that deinstitutionalization of our state hospitals has been directly responsible for increased incarceration rates, but the symmetry of these two trends is striking,” he said.

In Hamilton’s home state of Texas, 40 percent to 50 percent of mental health care consumers reported having at least once experience with criminal detention, Hamilton said. “Ironically, because of the ways we’ve structured the laws in Texas and many other states, a person can appear dangerous enough to be arrested but. . . not dangerous enough to be hospitalized.”

The Texas Criminal Justice Policy Council found in 2001 that 19 percent, or 29,000, of those in the state’s jails and prisons had been admitted into the state’s public mental health system over the previous five years, according to Hamilton.

In addition, the Texas Council on Offenders With a Mental Illness found that among 15,700 prisoners receiving psychiatric medications in 2000, 50 percent to 70 percent were nonviolent offenders.

The economic ramifications of incarcerating people with mental illness are enormous, Hamilton said. Prisoners with mental illness serve longer sentences than others because they are more likely to get in trouble. Also, because they are held in a nontherapeutic environment, they may be more difficult to treat after release.

While the average prisoner costs the state about $22,000 a year, estimates of costs associated with prisoners with mental illness range from $30,000 to $50,000 a year, he said.

Alternative programs for nonviolent offenders with mental illness that provide food, shelter, housing, and mental health treatment upon release can cost as little as $10,000, Hamilton said, and reduce recidivism rates.

“Texas has 8,000 to 20,000 inmates who are potential candidates for such programs,” which would save the state anywhere from $80 million to $440 million before correcting for recidivism, Hamilton said.

The possibility of saving so much money appeals to state legislators, he observed. “How did conservative Texas legislators react when they were asked for $780 million to build more prison beds?,” he asked. “They rejected the proposal and instead charged the Texas Department of Criminal Justice with finding $35 million to enhance mental health services for prisoners” and the development of a comprehensive plan for juveniles at risk for incarceration because of mental illness, including substance abuse disorders.

“We have the potential to do the right thing while potentially saving millions of dollars,” he added. ▪