Experts See No Relief From Medicaid Cost Cutting

States’ spending growth on Medicaid has slowed, but reports from the Kaiser Commission on Medicaid and the Uninsured (KCMU) suggest that the program’s troubles are becoming more complicated and intractable.

In late September, KCMU released its third annual survey concerning states’ actions related to the cost of Medicaid. States reported that the average spending growth for Medicaid in 2003 was 9.3 percent, down from 12.8 percent in 2002. This figure marks the first time since 1996 that the growth rate has decreased.

The survey was conducted by Health Management Associates for KCMU in June 2003, which is the end of the fiscal year for most states.

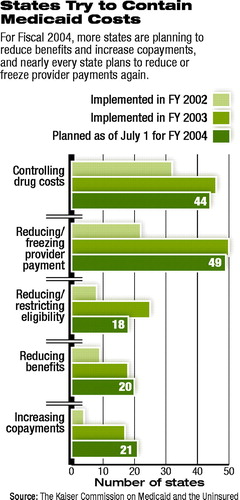

The two most frequently used strategies for cost containment were “controlling drug costs” and “reducing/freezing provider payments” (see chart).

The two most frequently used strategies for cost containment were “controlling drug costs” and “reducing/freezing provider payments” (see chart).

Robert Day, director of Medicaid and Medicaid Policy for Kansas, said at a press conference on September 22 announcing the survey and related reports, “We can control pricing because generally. . . . Medicaid’s the worst payer in the business. . . . We pay physicians poorly.”

Susan Fleischman, M.D., director of the Venice Family Clinic in Los Angeles, said that the California state legislature had enacted a 15 percent cut to providers over three years.

She told the audience, “[F]ive years ago, there were 42 providers who saw Medicaid patients in my part of Los Angeles. Now there are 22. . . . Most of them are closed to new Medicaid patients.”

The complexity and likely longevity of the problems concerning Medicaid are indicated in a companion report issued by KCMU, “The Current State Fiscal Crisis and Its Aftermath.”

That report, which was prepared for KCMU by Donald Boyd, Ph.D., director of the Fiscal Studies Program of the Nelson Rockefeller Institute of Government, found a dramatic decline in state tax revenue. In fact, Boyd found that measured as a share of the economy, the falloff was twice as steep as the state revenue declines that occurred during the recessions of 1990-91 and 1980-82.

He reported that “the fiscal crisis facing states is far worse than the condition of the nation’s economy.” The main reason state tax revenue fell so sharply, Boyd claimed, is that it had been propped up in the late 1990s by “unsustainable forces—especially the run-up in the stock market—which have unraveled rapidly in recent years.”

“[The situation] doesn’t just sound bad. It is bad,” Boyd said.

Although state spending on Medicaid has increased every year since 1996, that increase has played a relatively small role in creating the states’ fiscal difficulties. In Fiscal 2002, the growth in Medicaid spending contributed an estimated $6.9 billion to state budget shortfalls, while the drop in revenue collections contributed $61.8 billion to the gap, according to Boyd.

The result is that although further cost-containment measures will be directed at Medicaid, those measures cannot resolve or do much to alleviate state budget crises. Pressures for further cost cutting likely will result.

Boyd pointed out other factors that contribute to a bleak outlook for state budgets. Many states used now-depleted reserve funds to fill gaps in budget shortfalls or addressed the problem with measures, such as bond issues, that will exacerbate problems in the future.

He wrote that “prospects for substantial and sustained increases in federal aid to states appear dim.”

Boyd cited projections from the Congressional Budget Office that the federal budget deficit will amount to $1.4 trillion for the period 2004 through 2008 and noted that “these projections do not reflect most of the costs of Iraq and its aftermath”; they also assume that Congress will not enact a Medicare prescription drug benefit.

A second study, prepared by the Urban Institute and issued by KCMU, “Medicaid Spending Growth: 2000-2002,” found that spending on the “disabled” was the largest contributor to Medicaid expenditure growth in terms of enrollment category.

During the period 2000-02, expenditures on disabled individuals accounted for 34.3 percent of expenditure growth. The “aged” ranked second at 24.3 percent.

Lead author John Holahan, Ph.D., wrote, “Increases in enrollment of the aged and disabled far exceeded growth in the population, and this growth [trend] is likely to continue for some time.”

He cited the “high use of prescription drugs” by those two categories of enrollees as a source of expenditure growth.

“Medicaid Spending: What Factors Contributed to the Growth Between 2000 and 2002?” is posted on the Web at www.kff.org/content/2003/20030922/presentslides.pdf. “The Current State Fiscal Crisis and Its Aftermath” is posted at www.kff.org/content/2003/4138/4138.pdf. ▪