School Performance Suffers When ADHD Complicated by Executive-Function Deficits

Children with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) often do poorly in school because they are disorganized, can’t manage their time, and fail to plan.

Children with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) often do poorly in school because they are disorganized, can’t manage their time, and fail to plan.

Researchers have found that many of these children have deficits in executive functioning. “This is a system in the brain that is responsible for managing processes that are needed to problem solve and attain future goals,” according to principal investigator Joseph Biederman, M.D.

He and colleagues from the pediatric psychopharmacology unit at Massachusetts General Hospital in Boston described their research last month at the annual meeting of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry in Miami.

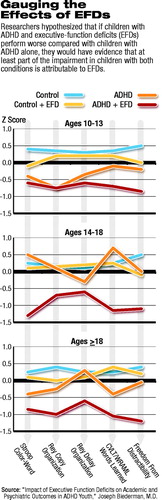

Biederman’s research team found that between 30 percent and 40 percent of children with ADHD had deficits in executive functioning, compared with only about 10 percent of control subjects.

There were 259 children with ADHD and 222 controls enrolled in the study. Each group was divided into those with or without executive-function deficits. The age range was 6 to 17 years, and there were 223 boys and 260 girls enrolled.

“Academic performance was worse in children with ADHD and executive-functioning deficits than in children with ADHD alone. They scored lower than any other group on organizational skills, language, and freedom from distractibility. They had lower intelligence scores, were more likely to repeat a grade, require tutoring, and be placed in special education classes,” Biederman told Psychiatric News.

The researchers controlled for learning disabilities, socioeconomic status, and IQ scores.

“We are continuing to study these children into adulthood to determine what course their disorder takes. This will inform the development of more effective treatment,” said Biederman. ▪