High-Level White House Advisor Describes Struggle With Depression

For ABC News anchor George Stephanopoulos, some of the very characteristics that marked his rise to the forefront of the Clinton administration as senior advisor to the president for policy and strategy were also harbingers of an impending depression—a feeling of always needing to achieve more, for instance, because he was not measuring up to his own standards.

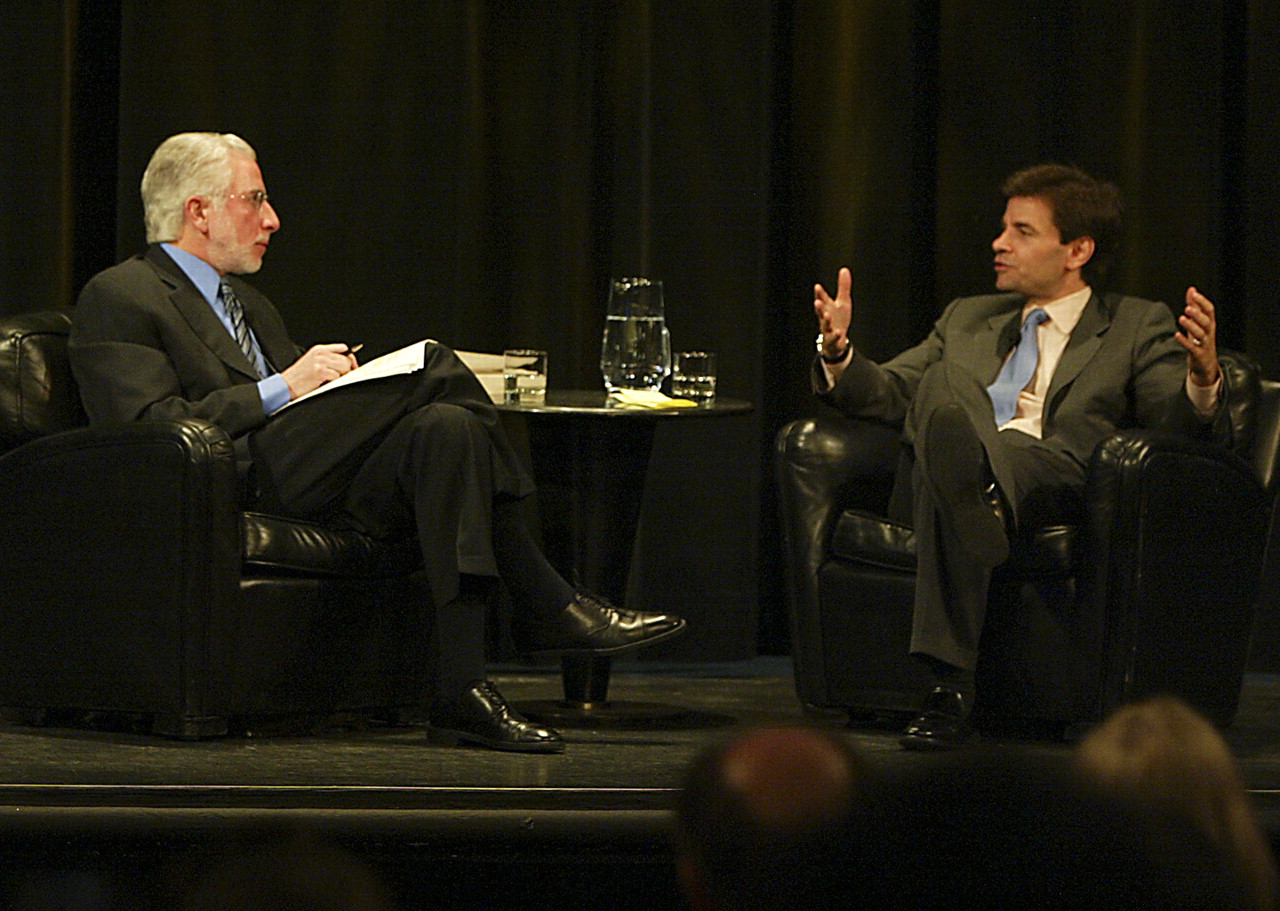

Lloyd Sederer, M.D. (left), and George Stephanopoulos discuss the unique pressures Stephanopoulos faced while serving in the Clinton administration as the senior advisor to the president for policy and strategy.

“For a long time, things that later turned out to be a problem for me were also key to my professional success,” he told psychiatrist Lloyd Sederer, M.D., who is executive deputy commissioner for mental hygiene in New York City and a former director of APA's Division of Clinical Services.

Stephanopoulos sat down with Sederer for the third annual Conversations event of the American Psychiatric Foundation last month at APA's 2004 annual meeting in New York City. AstraZeneca provided an educational grant to support the event.

The two discussed aspects of Stephanopoulos's depression, subsequent recovery, and views on how the subject of mental illness is portrayed in the media. Stephanopoulos has written about his experiences with depression in his 1999 autobiography, All Too Human.

Looking back at the once-in-a-lifetime educational and professional opportunities— such as a Rhodes scholarship that enabled him to study at Oxford University in England in his early 20s and his later stint in the White House—Stephanopoulos noted signs of his then-unrecognized depression.

Of his time in the White House, he said, “This was an unprecedented privilege, and I didn't feel like I was taking it all in and appreciating the things I was seeing.”

Instead of fully realizing the importance of his work, he said, “I was just getting through the day.”

A few months after the suicide of Deputy White House Counsel Vince Foster in July 1993, whom Stephanopoulos considered a friend, he began seeing a therapist.

His description of his therapist was met by laughter from audience members—“I guess you could say she was somewhat old school and didn't talk much,” he noted.

Initially, a central concern for him was the confidentiality of his therapy sessions—if subpoenaed, for instance, would laws prevent his therapist from having to divulge the contents of their sessions? Only after researching confidentiality laws and getting his therapist's assurance that the sessions would be kept private were his worries put to rest.

In therapy, Stephanopoulos said, he struggled with issues that are common to many patients but that for him were pronounced due to the nature of his work. “I had this issue where I always felt like I was on stage and was being watched—which was true,” due to his high-profile job, he noted.

He also had a tendency to “internalize things” and “worry that things could go wrong,” he said. “It turned out that in the first year of the Clinton White House, I did have responsibility for a lot of things, and a lot of things were going wrong,” Stephanopoulos observed.

His symptoms began to manifest themselves physically—he developed rashes and experienced insomnia frequently. Another symptom threatened his ability to function normally—“I couldn't break the sensation of nails [scraping] on a chalkboard or fork tines on a plate,” he recalled.“ I could imagine the sound at any moment, and once it started, it wouldn't go away.”

After being referred to a psychiatrist, he began taking an antidepressant medication, and many of his symptoms disappeared “relatively quickly,” he said. “I could both do my job and enjoy what I was supposed to enjoy and was so much more clear than I had been in about a year,” Stephanopoulos said. He discontinued the medication after leaving his post at the White House because “the drugs were not necessary when I was not dealing with that day-to-day kind of stress,” he noted. He said he continues to be involved in psychotherapy.

Although he believes there is less stigma surrounding mental illness than in years past, Stephanopoulos said, “there is still a ways to go” in terms of providing access to care. “People are becoming more and more aware of what mental illness is... yet we haven't expanded our ability to care for those people who are now aware they have a problem.”

In his opinion, those who have helped to raise awareness of mental health issues include CBS News correspondent Mike Wallace, who has spoken openly about his experiences with depression; Robert Boorstin, who served as special assistant to President Clinton and who has written about his experiences with bipolar disorder; the late Sen. Paul Wellstone, whom Stephanopoulos described as a “happy warrior and a special man”; Tipper Gore, wife of the former vice president; Sen. Pete Domenici (R-N.M.); and ABC News medical analyst Tim Johnson, M.D.

“Talking matters,” Stephanopoulos told Sederer. “Talking about these issues openly is important.” ▪