Proposed Drug Guidelines Get Negative APA Review

APA added its voice to a wide-ranging chorus of dissatisfaction at a public hearing last month on the proposed framework of drug categories and classes to be covered by the new Medicare Part D prescription drug benefit that starts in 2006. The framework, said APA and others, is wholly inadequate to address the diverse clinical needs of a heterogeneous patient population, such as those with mental illness.

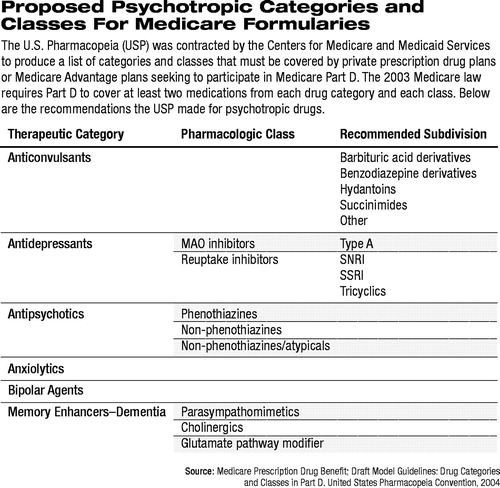

The proposed framework of categories and classes, referred to as the Model Guidelines, was developed by the United States Pharmacopeia (USP). The USP was contracted by the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) to produce a list of categories and classes that must be covered by any private prescription drug plan (PDP) or Medicare Advantage plan seeking to participate in Medicare Part D (Psychiatric News, December 19, 2003).

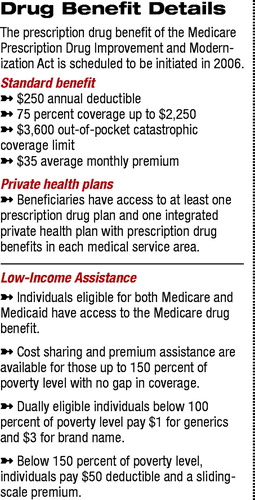

Under the Medicare Prescription Drug Improvement and Modernization Act (MMA), signed into law by President Bush last December, any drug plan participating in Medicare Part D would be required to cover at least two medications “within each therapeutic category and class of covered Part D drugs, although not necessarily all drugs within such classes.”

In accord with the MMA, CMS noted two key objectives regarding the therapeutic categories and classes: to prevent undue discouragement of enrollment by intended beneficiaries and to prevent discriminatory formulary practices by drug plans.

“Our preliminary evaluation is straightforward,” Steven Daviss, M.D., president of the Maryland Psychiatric Society, testified on behalf of APA. “The USP draft categories and classes compress the available pharmacologic agents in a manner that is inconsistent with appropriate organizing principles for these drugs and inconsistent with accepted practice in the field. We find that the draft categories and classes are wholly inadequate.”

The USP noted in the draft Model Guidelines that indeed the guidelines are not a formulary—“they represent a first step in helping plans develop their formulary structures.” The USP established an Expert Committee to develop the guidelines and also formed “advisory forums” to represent beneficiaries, drug plans, pharmaceutical manufacturers, and providers.

In all, the expert committee was made up of 18 members from academia, the National Institutes of Health, large health systems and health insurers, and pharmacy benefit providers. The four advisory forums drew input from an equally broad array of experts, representing 20 groups. For example, AARP and Consumers Union representatives served on the beneficiary advisory forum, and the providers advisory forum was made up of representatives from the American Academy of Family Physicians, American College of Physicians, American Geriatrics Society, and American Nurses Association. Representing pharmacists as providers were the Academy of Managed Care Pharmacy, American Society of Consultant Pharmacists, and American Society of Health System Pharmacists.

Between January and August, the Expert Committee met numerous times and contracted with outside consultants to advise in the development process. The committee developed a classification system “that begins with a disease-linked therapeutic category (generally reflective of indication), follows with pharmacologic class (primarily based on mechanism of action), and includes a further subdivision where needed.”

Six Categories Proposed

With respect to psychotropic medications, the Model Guidelines propose six broad categories with eight classes of medications and nine subdivisions (see table at right).

“We believe that the draft Model Guidelines fail to adequately account for different mechanisms of action of the psychotropic drugs used in persons with mental illnesses,” Daviss told Psychiatric News.

At least two drugs from each category would have to be covered by any PDP participating in Medicare Part D. For example, only two anticonvulsants would need to be on a formulary, as well as two anxiolytics and two “bipolar agents.” None of these three categories, however, is broken down into different classes of medications. Bipolar agents could include many anticonvulsants and most newer antipsychotics, yet there is no requirement that any more than the two least-expensive “bipolar agents” would have to be covered.

In the proposed antipsychotic therapeutic category, APA testified,“ differentiation between phenothiazine and non-phenothiazine antipsychotics has little clinical significance.” In addition,“ the proposed non-phenothiazine, atypical class lumps together six very different medications which exert their clinical effects through at least two separate mechanisms of action.”

Likewise, the antidepressant category is divided into two classes, with the serotonin reuptake inhibitors, norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors, combined serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors, and the tricyclics all lumped together. Thus, a PDP's formulary could cover a generic tricyclic and generic fluoxetine only and still meet the requirements of the Model Guidelines.

The lack of appropriate access to prevailing first-line treatments carries a high probability of discouraging enrollment of certain beneficiaries in a Medicare PDP, Daviss stressed. The guidelines would also allow PDPs to“ risk-select” by offering older or less expensive and less effective agents, thereby again discouraging patients currently stabilized on newer, higher-cost medications from enrolling.

“Any formulary guidelines, therefore, or framework for therapeutic categories and classes that force a pharmacological homogeneity, which does not in fact exist, onto a highly heterogeneous clinical population and classes of pharmacologic agents may well be discriminatory on their face. Similarly situated patients with mental illness will not likely have equal access to appropriate first-line treatments.”

Widespread Concern Expressed

The public hearing was well attended, and the vast majority of those speaking during the comment period expressed concern on a number of levels.

John Gates, M.D., representing the American Academy of Neurology, noted that the persons most likely to be covered under Medicare Part D will be those who have multiple comorbidities and need access to a wide variety of drugs at different times. The standard approach “of two medications from each category or class is unacceptably restrictive,” he said.

Gates also stressed that it is poor judgment to decide whether to include a medication in a formulary on the basis of cost alone. The decision, he said, must be multifaceted, and above all else, “the sum of efficacy plus tolerability is the true measure of a medication's success or effectiveness. It does not matter how effective a low-cost medication is if patients cannot tolerate its adverse effects.”

Representatives from the American Society of Health System Pharmacists and the American Society of Consultant Pharmacists suggested that the development strategy of the Model Guidelines was fundamentally flawed. Both noted in oral testimony that many disparities existed in the weight given to various categories and classes.

For example, ASCP noted that in the list of categories, “35 or more antihypertensive combination products are lumped into a single category,” and “all 23 cephalosporin antibiotics” are also combined in a single category. Finally, they noted, “SSRI and SNRI antidepressant medications are combined... despite distinct pharmacological differences.” Expanding and separating these drugs into more distinct groups “would help ensure access to an adequate number of these critical medications.”

In oral testimony APA's Daviss reiterated APA's request to be considered“ a participant in the USP deliberation process” and formally included in “one-on-one” consultation with CMS and the USP in the development of the final guidelines.

“This is 2004,” Daviss stressed. “These historic changes to Medicare need to bring the treatment of mental illness into the 21st century. Americans with mental illness deserve an alternative, flexible classification system for psychotropic medications that accounts for mechanism of action, side-effect profile, and metabolism so that citizens will have a safe and clinically reasonable choice—regardless of race, gender, age, liver action, renal function, or other illness comorbidity.”

More information on the USP Model Guidelines can be accessed online at<www.usp.org> by clicking on “USP to play a critical role in creating Medicare Model Guidelines.” ▪