Many More People Seeking MH Treatment Since 1980s

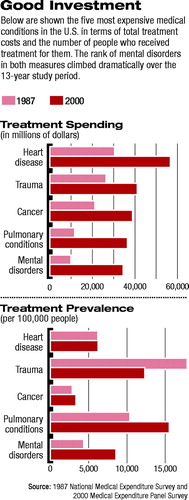

Mental illness was among the top five conditions accounting for rising health care costs between 1987 and 2000, and most of that spending stemmed from an increase in the prevalence with which these disorders were treated.

Total health care spending increased by $199 billion (in real 2000 dollars) during that period, and mental illness accounted for approximately 7.4 percent of that increase, according to a report in the August Health Affairs.

That places mental illness second among 15 conditions that contributed the most to rising health care spending, behind only heart disease, which accounted for about 8.1 percent of the total increase in spending.

Pulmonary conditions accounted for approximately 5.6 percent of the total increase in spending, cancer accounted for approximately 5.4 percent, and hypertension accounted for about 4.2 percent, said study author Kenneth E. Thorpe, Ph.D., and colleagues.

The other 10 conditions, in descending order of their contribution to the increase in health care spending, were trauma, cerebrovascular disease, arthritis, diabetes, back problems, skin disorders, pneumonia, infectious disease, endocrine disease, and kidney disease.

Moreover, in an analysis examining the factors that accounted for a rise in spending for the conditions, it was a rise in treated prevalence of mental disorders that accounted for 59.2 percent of the change in spending on those disorders between 1987 and 2000.

Further analysis of the mental health care spending found that increasing population accounted for 19.7 percent of the change, and an increase in cost per treated case accounted for 21.1 percent.

Thorpe told Psychiatric News that the sharp rise in treated prevalence reflects two trends: increasing recognition and diagnosis of mental disorders, particularly depression, and a rapid expansion in the number of new psychotropic medications.

“People with mental disorders seem to be accessing the medical care system at a higher frequency,” Thorpe told Psychiatric News.“ There has been increased public awareness combined with the fact that physicians are better able to diagnose and understand these symptoms than they were 15 or 20 years ago. Psychiatrists, in particular, have a broader tool kit to treat people with mental illness, and this has made it possible for treatment options to be provided to these patients.”

And although the researchers acknowledged that the data do not suggest whether increased spending is “worth it” in terms of improved health, Thorpe and colleagues specifically highlighted treatment of mental illness as one case in which the spending increase is probably worth the cost.

“Given the historical underdiagnosis and treatment of disorders such as depression, this wider use of treatments, and the associated increase in health care spending, is likely to represent benefits that outweigh the cost,” they wrote.

Thorpe is a professor of health policy at Emory University School of Medicine.

APA leaders welcomed the study as a testament to the success of treatment for mental illness.

“Mental disorders are being treated more frequently today because treatment works,” APA President-elect Steven Sharfstein, M.D., told Psychiatric News. “Stigma, although still a problem, has been reduced as more and more individuals and families demand expert diagnosis and treatment. This is true for all age groups, but especially for children and adolescents. Now we need to ensure there is adequate funding for effective care.”

Health services and economics researcher Howard Goldman, M.D., editor of the APA journal Psychiatric Services, emphasized that the study highlights the case of mental illness as an example of rising health care spending that is actually beneficial.

“We should be welcoming increased spending where treatment is effective and improves health,” Goldman said. “We should be alarmed about costs if they are associated with treatment that is ineffective. This study clearly comes down in recognition of treating mental disorders as likely to bring greater health.”

Goldman also noted that the study design was based in part on similar research by psychiatrist Benjamin Druss, M.D., in a study titled “The Most Expensive Medical Conditions in America,” published in the April 2002 Health Affairs.

Using the 1987 National Medical Expenditure Survey and the 2000 Medical Expenditure Panel Survey, Household Component, Thorpe and colleagues calculated the level and growth in health care spending attributable to the 15 most expensive medical conditions in 1987 and 2000.

For each patient, they calculated total annual spending and total spending for each of 259 medical conditions. Then for the 15 conditions with the largest nominal growth in spending between 1987 and 2000, the researchers tabulated total annual spending by medical condition in 1987 and 2000 and the change in spending as a percentage of the change in national health spending among the noninstitutionalized population.

In analyzing change in spending, the authors calculated an upper-bound and a lower-bound range for the percentage of change in total health spending that is associated with each condition. This was done to account for the fact that a single medical encounter may include treatment for more than one condition, resulting in overestimating spending for the primary disorder while, in contrast, using spending amounts for which there is only a primary disorder reported would be liable to underestimate spending on that condition. The authors then calculated an amount between the upper and lower bounds that was a “best-guess” estimate of the actual spending for a condition.

Finally, the researchers broke down the change in spending by medical condition into that which was attributable to increasing population, that which was attributable to an increase in the cost per treated case, and that attributable to a rise in treated prevalence.

They found that between 43 percent and 61 percent of the total nominal change in spending between 1987 and 2000 was attributable to the 15 conditions; the “best-guess” estimate is that 50 percent of spending was attributable to these conditions. Most of this change was attributable to the top five conditions: heart disease, mental disorders, cancer, pulmonary disease, and hypertension.

Perhaps most startling, a rise in treated prevalence accounted for 59.2 percent of the increase in spending on mental disorders between 1987 and 2000. That was the highest among the five conditions and was second among the 15 conditions (behind cerebrovascular disease).

Thorpe noted that health services research has typically looked at increased spending as a function of payment rates to hospitals and physicians, and the focus on specific medical conditions is relatively unique in the literature.

And he said the results suggest that some of the concern about rising health care costs is misplaced: if it is purchasing increased health benefits, the increased cost may be worthwhile.

“Looking at health spending this way focuses our cost-containment efforts in a different place,” Thorpe said.

The article, “Which Medical Conditions Account for the Rise in Health Care Spending,” is posted online at<http://content.healthaffairs.org/cgi/content/full/hlthaff.w4.437/DC1>.▪