Psychiatric Illness May Affect Data on `Healthy' Subjects

One of the hallmarks of medical research, including psychiatric studies, is the use of “healthy control” subjects against which a population of interest is compared.

Yet it looks as though a large number of persons who volunteer to serve as control subjects have personality disorders, a new study suggests.

The study was conducted by Emil Coccaro, M.D., chair of psychiatry at the University of Chicago, and colleagues. Results appear in the July Journal of Psychiatric Research.

Some 340 individuals who answered a newspaper ad looking for people to participate “in a medical research study of hormone response” and to be paid for it were the focus of the study. Coccaro and his coworkers used structured clinical interviews—the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM Diagnoses and the Structured Interview for the Diagnosis of DSM Personality Disorder (SIDP)—to determine whether any of the volunteers currently had or had a history of any psychiatric disorders, and if so, which ones.

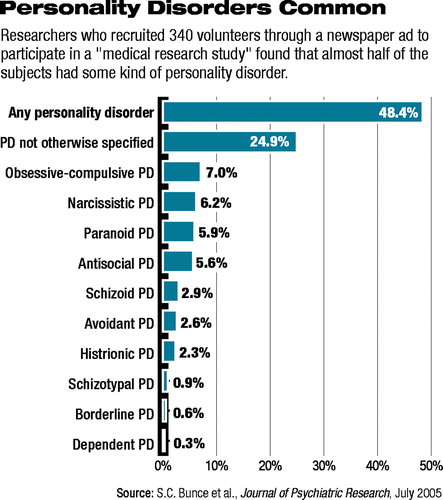

They found that 45 percent of these volunteers had a lifetime history of one or more Axis I disorders and that 48 percent of these volunteers had a personality disorder.

Moreover, the most frequent personality disorder diagnosis was personality disorder not otherwise specified (25 percent of those with a personality disorder), followed by obsessive-compulsive disorder (7 percent), narcissistic personality disorder (6 percent), and paranoid personality disorder (almost 6 percent).

Furthermore, volunteers with personality disorders were found to differ from volunteers without such disorders in clinically significant ways. For example, they tended to exhibit more impulsivity, affective lability, trait anxiety, hostility, and aggression than the latter group did.

These findings have important implications, the researchers believe. For example, with regard to Axis I disorders, the lifetime history of psychiatric disorders found in these subjects is quite close to the 48 percent found in studies of the general American population. Thus the subjects may well represent the general population on this comparison. However, while 48 percent of the subjects were found to have a personality disorder, only 15 percent of the general American population meets criteria for such a diagnosis (Psychiatric News, September 3, 2004).

And even if such individuals were a true random sample of Americans, investigators would probably not want to use them as “healthy controls” since there is reason to believe that some of the characteristics they possess could bias study outcomes, Cocarro and his coworkers indicated in their report. For instance, studies have shown that trait anxiety can influence hypertension, and impulsiveness can alter neurotransmitter activity.

The problem, Cocarro and his team concluded, is that while most scientists screen potential control subjects for Axis I disorders (at least in psychiatric research), they do not screen them for Axis II disorders. Hence individuals with personality disorders can easily be enrolled to serve as controls and thus may bias research outcomes.

“Two methodologic issues may compromise these data to some extent,” Paul Appelbaum, M.D., told Psychiatric News. In addition to being chair of psychiatry at the University of Massachusetts and a former APA president, Appelbaum has written extensively on the use of mentally ill subjects in research studies.

“First, these subjects were recruited from a newspaper ad that began by stressing the money that was being offered rather than, for example, the opportunity to contribute to advancing knowledge of hormone responses.... Thus, the findings of a high prevalence of personality disorders in the resulting group of volunteers may be specific to the means used here to recruit them. Focus on a desire for money when you recruit subjects, and you may get what you pay for. Second, the accuracy of the data is entirely dependent on the validity of the diagnostic method used. Structured instruments like the SIDP are known to overestimate—sometimes markedly—the rate of personality disorders in a sample.”

Yet assuming that the findings are valid, Appelbaum said, “they do suggest reason for caution in recruiting and screening subjects.... The authors suggest more intensive screening for personality disorders, but there are other solutions too. It may well be worth experimenting with the recruitment message, for example, stressing altruism versus self-interested motives, to see the effect on who volunteers. Or more epidemiologically valid methods of recruiting samples from the general population might be employed, rather than relying on newspaper ads.”

The study was funded by the National Institute of Mental Health.

An abstract of “High Prevalence of Personality Disorders Among Healthy Volunteers for Research: Implications for Control-Group Bias” can be accessed online at<www.sciencedirect.com> by clicking on “Browse A to Z of journals,” then “J,” then “The Journal of Psychiatric Research.” ▪