Positive Results Lead to Renewal Of Outpatient Commitment Law

A law mandating outpatient psychiatric treatment for people with serious mental illness in New York has been renewed with the hope that it will continue to reduce hospitalizations, arrests, and homelessness.

On June 30, the date that the five-year-old Kendra's Law was set to expire, New York Gov. George Pataki (R) signed legislation to extend the program for another five years.

The law is named for Kendra Webdale, a 32-year-old woman who in January 1999 was pushed into the path of an oncoming subway train by a man with untreated schizophrenia.

Seven months after her death, Pataki signed Kendra's Law. As of March, there were 3,908 people who had received court-ordered outpatient treatment, or assisted outpatient treatment (AOT), under Kendra's Law.

The legislation is meant to benefit seriously mentally ill people who, due to a history of noncompliance with treatment, cycle in and out of hospitals, jails, prisons, and homeless shelters.

To be eligible for AOT, the person's noncompliance must have resulted in either two psychiatric hospitalizations or treatment in a correctional facility in the prior three years or at least one threat or act of violence toward self or others in the prior four years.

The new law expands the list of those who can petition the courts to ask that a person be evaluated for AOT eligibility to include psychologists and social workers. The initial list included psychiatrists, parents, spouses, adult siblings, adult roommates, directors of hospitals in which the individuals are hospitalized, the mental health director or social services official for the county where the person lives, and parole or probation officers.

After the petition has been filed, a county-designated physician conducts a clinical assessment of the person to determine whether it is appropriate to pursue a court order for AOT.

Those who are deemed eligible for services under Kendra's Law are court-ordered to receive AOT in the community for up to six months. The treatment is usually coordinated through an AOT intensive case manager and, in some cases, an assertive community treatment team.

County mental health directors operate, direct, and supervise AOT programs. In New York City, the Department of Health and Mental Hygiene oversees implementation of AOT, which is administered by teams of employees of the New York City Health and Hospitals Corporation.

The New York State Office of Mental Health (OMH) is responsible for statewide implementation and monitoring of the AOT program.

The updated legislation includes a number of changes designed to improve the coordination and delivery of assisted outpatient treatment (AOT) for eligible recipients.

For instance, to facilitate AOT in rural areas with few psychiatrists, the law authorizes OMH “to make available to counties with a population of less than 75,000 a physician employed by OMH for the purpose of making the affirmation or affidavit required when filing petitions.”

The updated legislation also expands eligibility criteria somewhat by excluding the time a person spends in a psychiatric hospital or correctional facility from the period prior to the petition process.

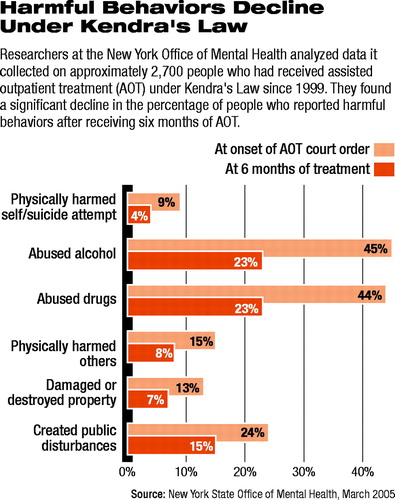

OMH has been evaluating outcomes for those in AOT from the start of the program to March, and the data were released in a report that OMH issued that same month.

The majority of the 2,745 recipients for whom data were available remained in treatment longer than the initial six-month court-ordered period. The average length of time in AOT was 16 months, according to the report.

When OMH researchers analyzed outcomes for recipients who completed AOT, they found that 23 percent had been incarcerated at least once in the three years before receiving AOT, while just 3 percent were incarcerated during their court-ordered treatment.

When researchers looked at the same three-year period preceding AOT treatment, they found that the vast majority (97 percent) had been hospitalized at least once, while just 22 percent were hospitalized while receiving AOT.

In addition, 19 percent of AOT recipients had been homeless before receiving AOT, while 5 percent were homeless during their treatment.

According to Mary Zdanowicz, J.D., director of the Arlington, Va.-based Treatment Advocacy Center, Kendra's law has “greatly improved quality of life” for its recipients in addition to reducing arrests and hospitalizations of seriously mentally ill people in New York.

She also credited AOT with improving New York's mental health system by ensuring that those who are eligible for treatment under Kendra's Law, a population she called “too often ignored and often underserved,” have a safety net.

Barry Perlman, M.D., president of the New York State Psychiatric Association (NYSPA) and director of psychiatry at St. Joseph's Medical Center in Yonkers, said that the OMH data indicate that Kendra's Law is promising. While NYSPA supports a time-limited continuation of the law, he said,“ we think additional research on services and financing is warranted” before a permanent renewal is legislated.

He noted that early OMH data suggested that most of the referrals to AOT from hospitals were coming from those operated under the auspices of local governments, such as municipal or county hospitals, rather than from the inpatient units of general, not-for-profit voluntary hospitals.

“This may be due to the expenses related to sending a staff psychiatrist to evaluate patients and attend court hearings to obtain AOT for patients,” which detracts from hospital revenue, he noted.

“NYSPA approved the change in the law that provided assistance in counties with 75,000 or less,” he said. “We hope that in the future the funding will be extended to all counties in the state regardless of population size.”

He said that such funding would provide strong encouragement for greater use of AOT by the staff of inpatient units of general hospitals.

More information on Kendra's Law is posted on the Web at<www.omh.state.ny.us/omhweb/Kendra_web/KHome.htm>. The legislation is posted at<assembly.state.ny.us/leg/?bn=A08954>.“ Kendra's Law: Final Report on the Status of Assisted Outpatient Treatment” is posted at<www.omh.state.ny.us/omhweb/Kendra_web/KHome.htm>.▪