Money Woes Take Toll On Local MH Services

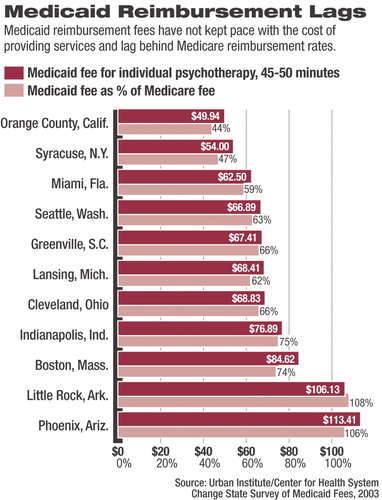

Community mental heath services appear to be eroding even further under state budgetary constraints and poor Medicaid reimbursement rates, according to interviews with local and state mental health leaders.

Physicians, mental health advocates, and state and local mental health officials in 12 randomly selected sites told researchers with the Center for Studying Health System Change that problems that have been apparent to community mental health leaders for several years—especially increasing incarceration and increasing use of hospital emergency departments by people with mental illness—appear to be getting worse.

The erosion of public mental health services appears to be fueled by the tendency of states to shift funding for mental health services to the Medicaid program, said Peter Cunningham, Ph.D., senior researcher at the Center for Studying Health System Change.

He is lead author of a report in the May Health Affairs titled“ The Struggle to Provide Community-Based Care to Low-Income People With Serious Mental Illnesses.”

“What we heard consistently across all communities and respondents is that there are pretty serious shortages in some key types of services, including residential support services,” Cunningham told Psychiatric News. “Psychiatric inpatient beds were considered in very short supply, to the extent that some people have had to go outside the community to get an inpatient admission.”

According to the report, residential services were consistently mentioned as being in short supply, including housing, group quarters, transitional shelters, and other support services. And although state and county psychiatric hospital capacity has been declining for several decades, capacity at private psychiatric hospitals and psychiatric units of general hospitals declined sharply during the mid- and late 1990s.

“Much of this decline could reflect the increasing emphasis on outpatient and residential care versus inpatient care, although some community respondents believe that this shift has occurred too quickly and that increases in outpatient capacity have not kept pace with the decreases in inpatient capacity,” Cunningham and colleagues stated.

Shortages of key outpatient care staff, especially psychiatrists, were reported to be worsening in most of the communities, resulting in longer waiting times. Between 2000 and 2003, the number of Medicaid recipients and uninsured people increased about 18 percent nationally, while the number of psychiatrists increased only about 3 percent, according to the report.

Interviews for the analysis were conducted as part of the Community Tracking Study, a longitudinal study conducted by the Center for Studying Health System Change every two and a half years. More than 1,000 health care leaders were interviewed from a wide range of organizations across the following 12 markets: Boston; Cleveland; Greenville, S.C.; Indianapolis; Lansing, Mich.; Little Rock, Ark.; Miami; northern New Jersey; Orange County, Calif.; Phoenix; Seattle; and Syracuse, N.Y. ▪