Late-Life Depression Improves With Care-Manager Program

A collaborative care management program for late-life depression produces long-term health care improvement at a steadily declining price, according to a study of the Improving Mood Promoting Access to Collaborative Treatment (IMPACT) approach.

The study, published in the December 2005 Archives of General Psychiatry, assessed over two years the costs and benefits of the IMPACT approach on 1,801 patients over 60 years old with major depression and/or dysthymic disorder.

The IMPACT one-year intervention featured either a nurse or psychologist care manager working in each participant's primary care clinic to support the patient's regular primary care physician. The care manager helped the primary care physician follow the patient's medication adherence, symptoms, and progress or lack thereof. Decisions about medication and therapy followed the experimental protocol.

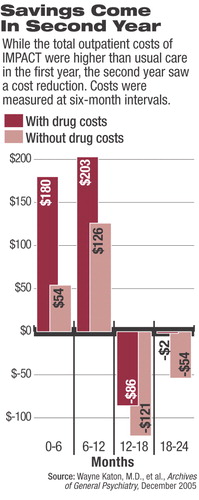

The study's lead author, Wayne Katon, M.D., said it differs from many previous depression care cost-effectiveness studies, which followed patients for only one year. This research found most of the health care costs for this type of care occur in the first year, while the benefits of reduced overall health care costs continue into the second year. Katon is a professor in the Department of Psychiatry and Behavioral Sciences at the University of Washington School of Medicine.

“What this study shows is that you continue to accrue benefits in the second year, so health care organizations investing in this may see some increased costs in the first year, but those are largely made up for in the cost savings in the second year,” Katon said.

The study found that total mental health care costs per patient were about $921 higher for IMPACT participants over the two years; however, other medication costs dropped $126 on average, and other outpatient costs were cut by $501. It also found average per-patient outpatient costs were $383 higher in the first year, but became an $88 cost savings in the second year, when intervention services ceased. When all medication costs were excluded, there was a net cost of $180 associated with intervention in the first year and a net cost savings of $175 in the second year.

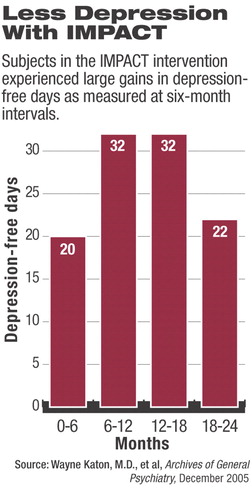

The benefit of the services seemed to hold throughout the study period, despite treatment ending at one year. The study found a mean of 52 depression-free days attributed to the intervention in the first year, while the mean number of depression-free days in the second year rose to 54 days.

Katon said the findings indicate that the benefit in reduced depression symptoms continues into the third year and perhaps beyond, with the medical care costs savings also continuing.

“Researchers are planning studies to confirm that,” he noted.“ It takes some investment up front to develop these kinds of programs. What is holding back the movement to provide chronic care are incentives for the health care systems to try this approach.”

Although the study followed a collaborative care model first described in 1995, it was modified to include some unique features, which Katon said appeared to improve outcomes.

One change was that patients were given a choice to start treatment with either psychotherapy or medication. Additionally, patients were allowed to augment their medication with therapy if they were not improving, and they could augment their therapy with medication if therapy alone did not appear to improve their condition.

“Disease-management programs that provide a choice can treat a wider group of patients because some patients have a strong feeling about what kind of treatment they want to start with,” Katon said.

Predispositions for or against medications or psychotherapy can affect patient adherence to treatment, he said. So giving the patients choice can improve their compliance. The additional step is especially important in patients over age 60, Katon said, because research has found they are much more reluctant to seek mental health services than are younger patients.

The researchers hope their study will change the current system in which only 10 percent of elderly patients with depression are ever seen by a psychiatrist or mental health professional. So for most elderly who have depression, a primary care physician is the source of care.

Many elderly are reticent to go for specialized mental health care because of stigma, ambulation problems, or priority assignment to other medical conditions.

“The only place that we can improve care would be in the primary care system for these patients,” Katon said.

Previous studies have tried to improve mental health screening in primary care settings and then refer elderly patients to specialized care. However, those studies have found that 50 percent of elderly patients who are referred to mental health professionals never make an appointment, and half of those who do make an appointment go only once or twice, he said. Studies that ask patients where they would like to get their mental health care overwhelmingly report it to be in primary care settings.

The study is posted at<http://arch-psyc.ama-assn.org/cgi/content/short/62/12/1313>.▪