'Scorecard' Shows Inadequacy Of Health, MH Care Systems

Large minorities of patients in public and private health programs do not receive the mental health care they need, according to the first systemwide“ scorecard” on how well the U.S. health care system is doing its job.

“The National Scorecard on U.S. Health System Performance” was developed by researchers at the Commonwealth Fund, a private foundation that supports independent research on health and social issues. The fund called the study the first comprehensive attempt to measure and monitor health care on 37 key indicators around the core dimensions of outcomes, quality, access, efficiency, and equity in one report. For each indicator, researchers compared performance nationally against benchmarks achieved either within the United States or by other countries.

The scorecard grading used a score of 80 out of 100 to indicate that a group in a given category was receiving adequate care. For mental health care, the average U.S. score for adults was 47 and for children, 59.

The scores were derived from ratios that compare the U.S. national average performance to benchmarks that reflect the performance achieved by top-performing groups. In general, the benchmark rate for each indicator was based on rates achieved by top-scoring countries or the top 10 percent of U.S. states, hospitals, health plans, or other providers. When patient data were available only at the national level, researchers compared national rates with the experiences of high-income, insured people—the benchmark group that the researchers thought were least likely to face barriers because of costs.

The U.S. health care system as a whole scored an average of 66, according to the report. Overall and in each subcategory, there were substantial gaps between performance at the national level and in states that provided the best health care.

“The scores are low in all major domains,” said Cathy Schoen, senior vice president for research and evaluation at the Commonwealth Fund, at a congressional briefing last month in Washington, D.C. “We do see pockets of excellence, so we know we can do better.”

For example, the United States scored among the best countries in the category of healthy life expectancy for residents at age 60.

Access to MH Care `Low'

One key finding in the report is that adults and children who need mental health services frequently do not receive them. Only 47 percent of U.S. adults with “serious mental health needs” and 59 percent of children in need of mental health care received any treatment for their disorders in 2003, the year from which the data were drawn.

“Rates for adults and children [were] low even among high-income groups, which would be expected to receive better care,” according to the report.

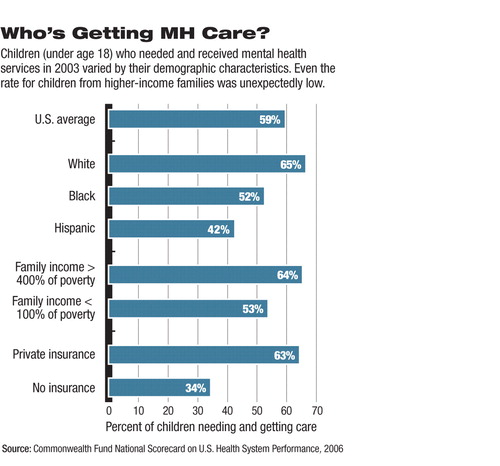

A little more than half of high-income adults (54 percent) and two-thirds of children in higher-income families—defined as families whose income was 400 percent of the federal poverty level or higher—received mental health care when needed.

The overall rate of children who needed and received mental health treatment was low, at 59 percent, said the researchers. For Hispanic children, the rate was 42 percent, while for white children it was 65 percent (see chart).

Failure to receive follow-up care after hospitalization for mental illness was common, said the researchers. On average, 46 percent of Medicaid patients, 39 percent of Medicare patients, and 24 percent of privately insured patients hospitalized for mental illness did not have a follow-up visit within 30 days of discharge.

The follow-up rates varied significantly across plans, ranging from a low of 22 percent in the bottom 10 percent of Medicaid plans to a high of 80 percent or more in the top 10 percent of private, Medicare, or Medicaid plans.

“Patients hospitalized for mental health conditions or congestive heart failure are known to be at risk for complications, and these patients experience high rates of readmission in the absence of effective discharge planning, transition, and follow-up care,” wrote the researchers, citing a 2003 Commonwealth Fund study, among other sources.

Improving the quality of care of the entire U.S. health care system to the level of the top 10 percent of the most cost-effective treatments now provided in some states could save up to 150,000 lives and $100 billion annually, according to the researchers.

Among their recommendations is that Americans should be guaranteed“ affordable” health insurance. They highlighted an Institute of Medicine estimate that the U.S. economy would receive $130 billion annually in productivity gains from providing health insurance to the uninsured, an amount that would more than offset the cost of the comprehensive insurance coverage.

Regardless of where they live, uninsured and lower-income adults and children are at high risk of not receiving recommended and basic care, noted the researchers. Only one-third of uninsured adults and children receive timely preventive care.

On a positive note, the researchers found that the large spread between average rates of hospital responsiveness to patients and the rates achieved by the top 10 percent of hospitals “reveals opportunities to reduce costs as well as lower risks to patients from improved care coordination.”

The lack of mental health care follow-up was one of the reasons behind the researchers' conclusion that poor care coordination is pervasive across the health care system, indicating a need for more integrated care “across sites of care and over time.”

“A National Scorecard on U.S. Health System Performance” is posted at<www.cmwf.org/publications/publications_show.htm?doc_id=401577>.▪