Latest Round of CATIE Data Sparks Many Questions

The largest study to date analyzing the cost-effectiveness of second-generation antipsychotic medications (SGAs) compared with first-generation antipsychotics (FGAs) has determined that treatment with the FGA perphenazine (Trilafon) is associated with, on average, a savings in total health care costs of $300 to $600 per month compared with SGAs.

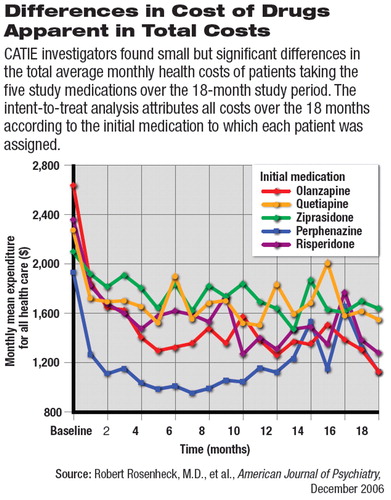

Furthermore, the study found that the difference in total monthly health care costs was due entirely to differences in the cost of the medications.

The new analysis, from the National Institute of Mental Health's Clinical Antipsychotic Trials of Intervention Effectiveness (CATIE), was reported by Robert Rosenheck, M.D., director of the VA's Northeast Program Evaluation Center and a professor of psychiatry, epidemiology, and public health at Yale Medical School, and his CATIE co-investigators in the December American Journal of Psychiatry. The team analyzed data comparing six antipsychotic medications—the FGA perphenazine versus the SGAs clozapine (Clozaril), olanzapine (Zyprexa), quetiapine (Seroquel), risperidone (Risperdal), and ziprasidone (Geodon)—on measures of health costs, symptom improvement, and several measures of effectiveness that address “health-related quality of life.”

What is likely to stir debate is the study's overall conclusion that treatment with an FGA, rather than an SGA, is associated “with no significant differences in measures of effectiveness,” including symptom and quality-of-life ratings. That debate will likely be spurred by an unusually frank editorial accompanying the publication of the study, which questions the study's methods, results, and conclusions (see box on page Original article: 59).

The CATIE protocol compared the real-world effectiveness of the antipsychotics through four phases of the complex study over a total treatment period of up to 18 months. Outcome data from phase 1 and phase 2 of the protocol have been previously reported (Psychiatric News, October 21, 2005; April 21). Phase 3 and 4 data have yet to be published in peer-reviewed reports.

Briefly, in phase 1, patients were randomly assigned to take one of the six antipsychotic medications above (except clozapine, which was only offered in phase 2). Patients who had tardive dyskinesia (TD) at baseline were prevented from assignment to perphenazine, which was thought at the time the study was designed to carry a higher risk of developing TD. Mirroring clinical practice, clinicians were encouraged to maximize dosing of each of the medications, increasing dose until either an effective dose was reached, the top of the dose range was reached, or intolerable side effects appeared.

If a patient and/or their physician believed an assigned drug was not effective, even after maximizing dosing, or if intolerable side effects appeared, the patient could be switched to another study drug. Each drug trial could last up to 14 weeks. Patients who did well on an assigned drug could remain on that drug in a follow-up phase for the remainder of the 18 months of the study.

Determining Cost-Effectiveness

Phase 1 results showed that patients stayed on olanzapine longer (with a median time to discontinuation of 9.2 months) than any of the other drugs before switching. No difference was found between perphenazine and risperidone, quetiapine, or ziprasidone.

Phase 2 of the study generally found that clozapine, despite its risks, was more effective than other second-generation antipsychotics. But if clozapine was not an option, olanzapine and risperidone appeared to be the next-best choices.

The CATIE cost-effectiveness analysis used as its two primary outcomes total health costs and quality-adjusted life year (QALY) ratings.

Total health costs (defined as costs of total health services use plus medications) were documented each month with a self-report questionnaire. The investigators tracked an exhaustive list of possible services, including inpatient, outpatient, and community mental health treatment and residential assistance services. Costs of various medical or surgical outpatient visits as well as emergency-room visits were also included.

Monthly medication costs were based on published average wholesale prices. For those patients covered by Medicaid or cared for in the VA system, monthly medication costs were adjusted to reflect the steep discounts and rebates on medication prices often negotiated between those two systems of care and drug manufacturers.

The QALY ratings take into account health-related quality of life that includes both “health gains,” such as beneficial effects of treatment, and “health losses,” such as those associated with side effects.

Data Analyzed Four Ways

The CATIE team performed four rigorous analyses, either including or excluding patients with TD at baseline, and including or excluding patients randomly assigned to ziprasidone, which was approved by the Food and Drug Administration and added to the CATIE protocol after the study began.

The December AJP report presents an “intent-to-treat” analysis of cost-effectiveness, in which all costs, symptom scores, and QALY ratings are analyzed based on a patient's initially assigned drug. Any changes that occurred over time were attributed to the effects of the initial drug assignment, regardless of whether the patient remained on that drug for the entire study period or switched medications.

Other analyses tracked patients who switched medications during the study (only 25.9 percent of patients remained on their initially assignment). One of those analyses, a report by Susan Essock, Ph.D., et al., appears in the same issue of AJP.

Costs Differ Significantly

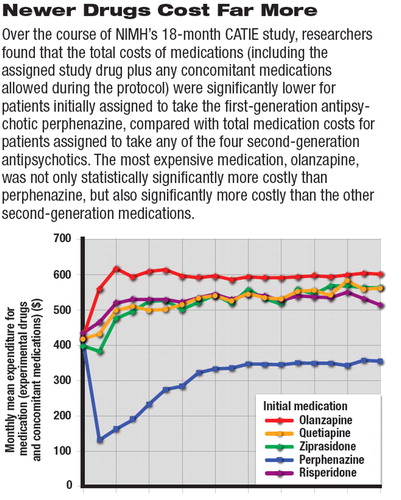

Average monthly medication costs (see top graph) for patients initially assigned to perphenazine were lower than medication costs for patients initially assigned to any of the four SGAs. In addition, drug costs for patients initially assigned to olanzapine were significantly higher than for patients assigned to quetiapine, risperidone, and ziprasidone. There were no statistically significant differences, however, in total health care costs between SGA groups.

There were no statistically significant differences between the groups of patients initially assigned to any of the five antipsychotics in the proportion of patients who received inpatient care each month or in costs per month for inpatient, residential, or outpatient health services.

Total health care costs for patients initially assigned to perphenazine were $300 to $600 per month per patient, lower than for any of the SGAs (see bottom graph).

Significant improvements in Qaly ratings were observed from baseline to 18 months for patients assigned to all five medications. Perphenazine was associated with higher (that is, better) QALY ratings than the other agents, but only one comparison was statistically significant: perphenazine was associated with higher ratings than was risperidone.

Finding Meaning Amid the Data

The CATIE investigators pointed out that CATIE was not long enough to detect any differences in costs that would be attributable to the long-term development of differential adverse effects, such as TD while taking an FGA, or the development of metabolic syndrome, diabetes, or cardiovascular disease while taking an SGA.

This lack of data on long-term costs, Rosenheck and colleagues cautioned,“ limits the conclusions regarding cost-effectiveness that can be drawn at this time.”

The CATIE investigators also cautioned that the relevance of their findings to FGAs other than perphenazine or to patients with schizophrenia materially different from the patients studied “is unknown.” For example, the CATIE findings cannot be extrapolated to “first-episode patients, refractory patients, the elderly, those with unstable medical problems, long-term institutionalized patients, patients who refuse to take medication, or patients with diagnoses other than schizophrenia.”

Despite all of their cautions, the CATIE team anticipated that some people will try to use the study results to change existing policy regarding access to antipsychotic medications within managed formularies.

“This study,” they emphasized, “would clearly not justify policies that would unconditionally restrict access to any particular medication or that would thoughtlessly force patients or doctors who are satisfied with a current treatment to change to a [different] treatment just because it might be less expensive.”

And while “[t]hese results should encourage consideration of older intermediate-potency drugs like perphenazine when a medication change is indicated,” the CATIE investigators noted, “the coming availability of generic second-generation antipsychotics will undoubtedly alter the cost profiles described here.”

“Cost-Effectiveness of Second-Generation Antipsychotics and Perphenazine in a Randomized Trial of Treatment for Chronic Schizophrenia” is posted at<www.ajp.psychiatryonline.org>.▪