Mentally Ill Youth Face Fear, Stigma From Adults

Children and adolescents treated for mental illness typically become outsiders at school, overmedicated, and “zombie”-like.

At least that's what many adults in the United States believe, according to a multidimensional analysis of the 2002 National Stigma Study–Children (NSS–C) survey published in the May Psychiatric Services in a special section titled “Culture, Children, and Mental Health Treatment.”

Conducted between February and June 2002, this is the “first large-scale, nationally representative survey of public knowledge, attitudes, and beliefs on children's mental health,” reported Bernice Pescosolido, Ph.D., an Indiana University sociology professor and lead investigator of the five-member survey research team.

The other team members were Brea Perry, M.A., Jack Martin, Ph.D., and Jane McLeod, Ph.D., of Indiana University's Department of Sociology, and Peter Jensen, M.D., of the Center for the Advancement of Children's Mental Health at Columbia University in New York City.

The survey's findings have serious public health implications for one of this country's most vulnerable populations.

“The general stigma attached to mental health treatment and specific concerns about the use of psychiatric medications for children challenge clinicians' efforts to provide appropriate and effective treatment to children and adolescents,” the researchers wrote. As previously reported in the literature, “services cannot be effective for families concerned about stigma because these families are unlikely to access available resources or accept recommended treatment options.”

The results of the 15-minute, face-to-face query of nationally representative samples of people (from the initial 1,393 noninstitutionalized individuals viewed) are contained in four companion analyses briefly summarized below. (See end of article for study methodology.)

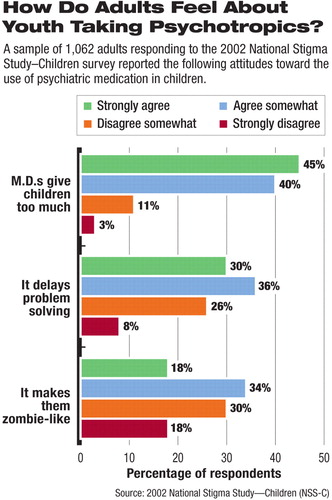

“Stigmatizing Attitudes and Beliefs About Treatment and Psychiatric Medications for Children With Mental Illness” The goals of this study were to examine attitudes of two types of pediatric interventions—defined as “mental health treatment” and“ medication”—to treat mentally ill youth and to assess the impact of stigma on obtaining treatment and “willingness” to use psychotropic medications. Investigators found that of a nationally representative target sample of 1,062 respondents (culled from the total 1,393 individuals surveyed), many perceived that children treated for mental illness are likely to be stigmatized. For example, 45 percent held the view that treatment for mental illness likely leads to rejection in school, and 43 percent believe that the stigma will follow a child into adulthood. Most surveyed (68 percent) strongly agreed or somewhat agreed that psychiatric medications have a long-term, detrimental affect on a child's behavior; 52 percent believed such medications leave children with a f lat,“ zombie”-like affect; and 66 percent said that such medications simply delay the patient and the family from solving real, behavior-related problems. The researchers concluded that the findings “revealed substantial stigma concerns, particularly surrounding medication options. These beliefs and attitudes cannot be easily inferred from adults' sociodemographic characteristics.” | |||||

“Perceived Dangerousness of Children With Mental Health Problems and Support for Coerced Treatment” Using data from a target sample of 1,152 individuals (from the total 1,393 interviewed), investigators sought to discern respondents' opinions as to whether mentally ill children are prone to harm themselves or others and how amenable respondents are to accept or seek forced, coerced treatment (legally enforced, mental health intervention, even against a child's will), to help them obtain needed treatment. Notable among the findings was that 33 percent of respondents perceived that a child with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) was somewhat likely or very likely to be dangerous to self, while 81 percent of respondents expressed the same thoughts about a child suffering from major depression. In comparison, 15 percent of respondents expressed similar, dangerous-to-self thoughts related to the control vignette describing an asthmatic child, while 13 percent expressed similar, dangerous-to-self thoughts when weighing the second control vignette, which described a child who suffered from a condition vaguely described as “daily troubles.” Although 35 percent viewed forced, legal coercion as a viable option to get treatment for a child with major depression, more than a third of those surveyed (42 percent) endorsed the same action as viable for a child suffering from asthma. The researchers concluded that “large numbers of people in the United States link children's mental health problems, particularly depression, to a potential for violence and support legally mandated treatment.” This seems “to reflect the stigma associated with mental illness and the public's concern for parental responsibility.” | |||||

“Public Knowledge, Beliefs, and Treatment Preferences Concerning Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder” The target sample of 1,139 respondents surveyed (from 1,393 initially interviewed) received a battery of short tests to discern their knowledge and attitudes about ADHD. They were asked a series of ADHD-specific questions after responding to the vignette part of the survey. Among the findings: Out of the 725 respondents who reported they had heard of ADHD (64 percent), 33 percent correctly described symptoms. Only 8 percent had knowledge of the primary medication (Ritalin) prescribed for ADHD, 5 percent viewed the cause of ADHD as being related to chemo-biological processes, and 16 percent knew someone who they believed had ADHD. “Women and those with higher levels of [formal] education were more likely to have heard of ADHD; African Americans, members of other nonwhite racial and ethnic groups, and older respondents were less likely to have,” wrote the researchers. Overall, 78 percent of people who had heard of ADHD viewed it as a“ real disease,” with most women, white people, and those with higher incomes concurring with that belief. And 65 percent supported counseling and medication as ways to treat it. “The public is not well informed about ADHD,” the researchers concluded. Future media and educational efforts should make “a special effort to reach specific populations such as men, nonwhite minority groups, and older Americans.” | |||||

“Comparison of Public Attributions, Attitudes, and Stigma in Regard to Depression Among Children and Adults” This study compared data from the 1996 and 2002 nationally representative General Social Survey modules on the public's attitudes about mental illness. Of those surveyed, a randomly selected subset of 193 responded to specific questions on a case-study vignette about an adult with major depression, while 312 responded to a case-study vignette of a child with major depression. Investigators found that 83 percent of those who read the adult vignette viewed childhood depression as more serious than adult depression, while 53 percent of those who read the child vignette viewed childhood depression as more serious than adult depression. Many respondents (40 percent) believed that seriously depressed children have a higher risk for violence than adults who are depressed. And while those who found treatments of all types valuable,“ significantly fewer recommended talking to family and friends about a child's mental health problem.” “Americans are more concerned about child depression than adult depression,” said the researchers, “and reveal more prejudice regarding perceptions of dangerousness. More respondents endorsed formal care versus informal care and advice. However, the heightened stigma surrounding childhood depression poses unique challenges for youth with depression and their families.” | |||||

This is “'a snapshot' of American views,” wrote Psychiatric Services editorial board member Bonnie Zima, M.D., M.P.H., in a commentary that accompanies the special section. “The [NSS-C] survey indicates that the public perceives disturbingly high rates of overmedication and stigma” affecting children and adolescents.

According to Pescosolido, in the article introducing the special section, much is empirically known about the attitudes, knowledge, and prejudices that Americans have about mentally ill adults. But far less is known about how society “views” its mentally ill children and adolescents or of the attitudes held by adults about the treatment options available to them. And yes, that's true, despite growing public interest in mental health news involving children ranging from deadly school violence to the pro and con debate about the safety of psychotropic medications for children and adolescents.

“We have known more,” she wrote, “about the stigma surrounding the occurrence of leprosy, diabetes, epilepsy, and developmental disabilities among children than we have about serious emotional disorders [among children.]”

The 2002 NSS-C Survey received project support from the National Science Foundation to the National Opinion Research Center, Eli Lilly and Co., the Office of the Vice President for Research at Indiana University, the National Institutes of Health, and National Institute of Mental Health.

The reports in the Psychiatric Services' “Special Section on the National Stigma Study-Children” can be accessed from the table of contents of the May issue at<http://ps.psychiatryonline.org>.

Methodology Used In Survey

The 15-minute, 2002 National Stigma Study–Children (NSS–C) survey was incorporated into one of two national samples of the 90-minute, face-to-face General Social Survey (GSS), thought to be the “longest running monitor of American opinions.”

The authors of the analyses, which was published in a special section in the May Psychiatric Services noted that “an institutional review board approval for [the GSS] was provided by the University of Chicago, and approval for the secondary analysis was given by Indiana University.”

A total of 1,393 noninstitutionalized U.S. adult residents participated in the survey, for a response rate of 70 percent (margin of error ±3.5 percent). Of these, wrote the researchers, “78% of respondents were white, 15% were African American, and 7% reported belonging to another racial or ethnic category (such as Asian American). Respondents' mean±SD age was 46±17.2 years. They had slightly more than a high school education (13.4 years) and a family income of $50,000±$39,500. Married individuals constituted 48% of the sample, 50% of the sample worked full-time, and 71% of respondents were parents. With the exception of the slight overrepresentation of women (59%), the sample mirrored the U.S. population profile within sampling error.”

The respondents were randomly asked to answer questions about a short written vignette on one of four topics, an NSS–C-specific technique developed by psychiatrist Peter Jensen, M.D., a study-team member.

Two vignettes described a subject who met DSM-IV diagnostic criteria for attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) or major depression. The other two “control” vignettes described a subject with asthma or a nebulous, subclinical condition called “daily troubles.”

The subject in each vignette was variously described as male or female, white or black, or age 8 or 14.

In the end, 24 percent of respondents (340 participants) were assigned to the ADHD vignette group, and 27 percent (374) were assigned to the depression vignette group. In the survey control groups, 23 percent of respondents (327) were assigned to the asthma vignette group, and 25 percent (352) were assigned to the daily troubles vignette group.

The reports in the Psychiatric Services' “Special Section on the National Stigma Study–Children” can be accessed from the table of contents of the May issue at<http://ps.psychiatryonline.org>.▪