Researchers in Hunt for Key to Preventing Schizophrenia

“I knew from the beginning there was something wrong with me.”

Call him “Sam.” He is a patient—or a“ client,” since he doesn't yet have a diagnosis—at a clinic whose purpose is not to cure him of illness, but to prevent it from happening. At 19, he looks and dresses like any of the thousands of young people at the nearby University of Toronto—jeans, T-shirt, and sneakers. There is little about him that marks him as a young man at risk for a severe mental illness; a slight nervousness maybe, as if he were watching his words or watching himself, fearful of slipping up.

On the surface, his story as he describes it is not so out of the ordinary either—a breakup with a girlfriend, spending a lot of time by himself, a sudden drop in his grades. But he also described an anomalous physical ailment, a sense of being paralyzed in his sleep.

“And then I began to feel that people were looking at me,” he said. “Like, if I was on a street corner in a crowd and I saw someone staring at me, I thought they might be watching me.”

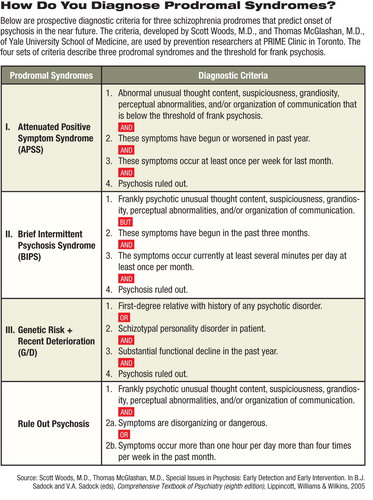

Figure 1: How Do You Diagnose Prodromal Syndromes?

“Sam” is a client at the PRIME (Prevention Through Risk Identification, Management and Education) Clinic in downtown Toronto, at the Centre for Addiction and Mental Health (CAMH). He agreed to share his story with Psychiatric News anonymously.

CAMH is affiliated with the University of Toronto and is Canada's leading addiction and mental health teaching hospital. Following referral by a college counselor and a lengthy battery of standardized psychological and neuropsychological tests—including the Scale of Prodromal Symptoms (SOPS), Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale (PANSS), Calgary Depression in Schizophrenia Scale (CDSS), and the Schizophrenia Predictive Instrument-Adult Version—he was found to be a risk for psychosis.

Staff at PRIME say the specificity of Sam's thoughts about who he believed was watching him and why—along with other symptoms—convinced them that he was on the verge of conversion to psychosis.

Now, he comes periodically to the clinic to talk to therapists and to psychometric “raters” who assess his progress (or his deterioration). And as a subject in a multicenter study looking at the efficacy of alternative methods for preventing or delaying the onset of schizophrenia, Sam is a participant in unique public-health initiative that is on a far frontier of schizophrenia research.

“Individuals who come to us say, 'A change has come over me, and I can't explain what it is,' ” PRIME Clinic psychiatrist Irvin Epstein, M.D., told Psychiatric News. “They are starting to feel that the whole world is strange to them, they don't feel right about themselves, they feel awkward in company or in school, and they are starting to lack focus and direction. They describe being anxious, but they don't know why, and they sense they are starting to lose their emotional connections to others.”

Today there is a growing scientific confidence in the validity of the“ prodrome,” the prepsychotic signs and symptoms that schizophrenia researchers believe precede an acute psychotic episode. As the science has progressed, identification of at-risk individuals has advanced beyond targeting those on the very cusp of psychosis to those who are even earlier in the developmental process of schizophrenia.

“The field is starting to mature,” Epstein said. “We are out of the period of infancy and uncertainty, and we now have a better idea of whom we should be targeting and what the symptoms are. Originally we were catching people on the verge of psychosis. These were people who didn't require a professional to appreciate that they were at risk of psychosis. In essence, what we were doing was trying to identify and to limit the extent of the inevitable psychosis.

“Now we are getting people who have a subjective sense that something in their world is changing, and it is really transforming the scope of what we are trying to accomplish from improving the outcome to really preventing the onset of a first episode.”

Better Predictive Model Sought

Yet prevention of schizophrenia remains an effort on the cutting edge of research and clinical practice and still has significant obstacles to overcome.

“Currently we have a set of criteria for the prodrome [see table], and if people meet these criteria, we know that approximately 20 percent to 30 percent will go on to develop schizophrenia,” said lead investigator at PRIME, Jean Addington, Ph.D. “That's good, and it's much better than if you simply follow those at genetic high risk. But it's not good enough to be treating people with medication. For our next step we really need to improve our predictive model.”

Whether they go on to develop psychosis or not, individuals who arrive at the PRIME Clinic in Toronto typically come of their own accord with serious psychological and emotional problems. “These people are help-seeking individuals who merit some kind of treatment in any case,” says Jean Addington, Ph.D.

Credit: Mark Moran

An important step toward that goal was taken with the publication of the May Schizophrenia Bulletin in which aggregated data on 888 at-risk and comparison subjects at eight sites participating in the North American Prodrome Longitudinal Study (NAPLS) were published. The NAPLS study is believed to be the world's largest sample of prospectively followed subjects at risk for schizophrenia.

Addington told Psychiatric News that the database provides an opportunity to explore fundamental questions related to prodromal psychosis, including descriptive phenomenology of currently accepted diagnostic criteria, conversion rates over a 30-month period, predictors of onset of psychosis and functional disability, and the impact of early treatment on the course of prodromal symptoms.

The eight sites in NAPLS, each of which is looking at different aspects of the prodrome and prevention, are the PRIME Clinic at the University of Toronto, Zucker Hillside Hospital in New York City, University of California at San Diego, Emory University, University of California at Los Angeles, University of North Carolina, Yale University, and Harvard University.

Prevention and False Positives

Prevention in any field presents ethical and methodological difficulties that treatment research does not: How is success measured when“ success” is defined as the absence of disease? And what are the implications of doing an intervention with individuals for a severe disorder that they may not go on to develop?

Prevention of severe mental illness, with the stigma that surrounds that label, only compounds the problem.

“If you want to try to do prevention, you have to start intervening with people before they have developed the full illness,” said Scott Woods, M.D., principal investigator in the Enhancing the Prospective Prediction of Psychosis study at Yale University. “You have to essentially make a prediction, and whenever you make a prediction about the future, it's possible you could be wrong. It is simply not possible to have an aim of doing prevention and always be right—not in this field or any other field.

“It's an area that people are uncomfortable with, but it is inevitable that you will be giving the intervention to some people who will never need it,” Woods continued. “We try to minimize the risk of stigmatization. We tell clients that we are not diagnosing a disease—we are diagnosing a risk. They may get worse and they may not.

“I like to turn the question on its head,” Woods added.“ Is there a risk of stigma if we don't identify people early? If we don't, and a person becomes fully schizophrenic, he or she may violate societal norms in a situation that can escalate into an emergency. Which is more stigmatizing?”

In Toronto, the location and appearance of the building where the PRIME Clinic is housed are deliberately contrived to be as work-a-day, as un-suggestive of a clinic treating pre-psychosis as possible. An old three-story Victorian house that stands unobtrusively near a corner of a busy intersection in the heart of Toronto's heavily trafficked university district, the building might be home to a group of trendy urban graduate students.

Also, although it is adjacent to the CAMH offices, no signage out front marks it as a prevention clinic. “You don't want to be inviting people to a schizophrenia program,” Addington said. “People find that stigmatizing. So we've made it as informal as possible. People ring the doorbell to get in, and the idea is that you are just coming to a clinic to take care of these symptoms you don't feel you should be having.”

She emphasized that the effort to prevent schizophrenia, while exciting, remains in the realm of clinical research until predictive criteria improve. She stressed that patients like Sam, whether they go on to develop psychosis or not, typically come to the PRIME Clinic of their own accord with serious psychological and emotional problems.

“These people are help-seeking individuals who merit some kind of treatment in any case,” she said.

As a subject in the Access, Detection, and Psychological Treatments (ADAPT) study, Sam has been randomized into one of two treatment arms, receiving either cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT) or a less-intensive treatment of regular monitoring of symptoms and supportive therapy.

Maria Haarmans, M.A., a therapist who has worked with Sam and others at PRIME Clinic, said that the hypothesis behind ADAPT is that “CBT will prevent or delay onset of psychosis” more effectively than monitoring.

“So many studies have shown how effective it is with mood disorders, but I've seen clinically that it also helps individuals who have anomalous experiences such as hearing voices,” Haarmans said. “Part of why CBT works is that it helps the person to cope with these experiences by providing normalizing information that can 'de-catastrophize' the meaning of the experience.”

If individuals in either treatment arm of the ADAPT study“ convert” to psychosis, they can be quickly treated with antipsychotic medication and other treatments in the First Episode Psychosis Clinic at CAMH.

“We are able to get [these subjects] into treatment within hours of their having a psychotic episode,” she said, noting that a significant body of research has shown that the earlier treatment begins, the better the prognosis.

For now, Sam is back in school and back in the swim of things as a 19-year-old. For a young man who has been told he is at risk for a devastating illness, one that carries severe stigma, Sam seems nonplussed, happy to have resumed his studies and a social life and grateful to have found PRIME Clinic.

“I get a lot of attention here,” he said.

More information on the PRIME Clinic is posted at<www.camh.net/Care_Treatment/Program_Descriptions/Mental_Health_Programs/PRIME_Clinic/index.html>.▪