Symptoms Linger Years Later for Terror Victims

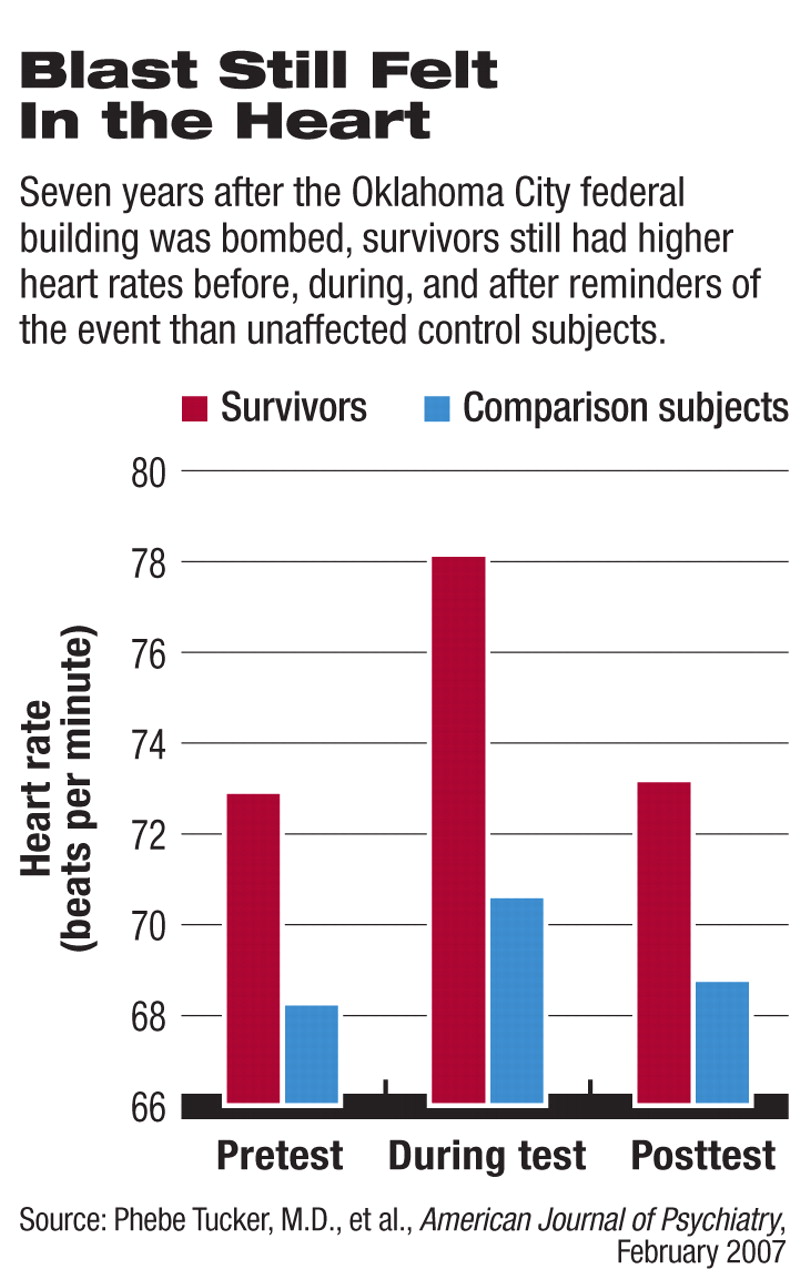

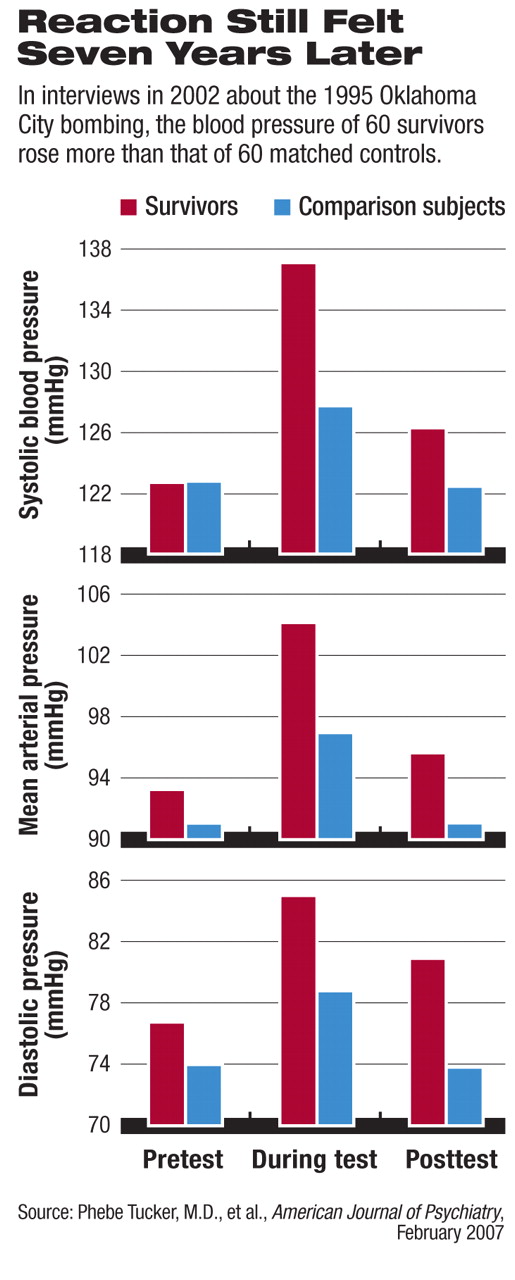

Seven years after the Oklahoma City federal-building bombing, blood pressure and heart rates still rose among apparently healthy survivors when they were reminded of the 1995 blast.

“These were selectively healthy people, not on heart or blood pressure medications or psychotropics, but they were still more physically responsive than a comparison group,” said Phebe Tucker, M.D., a professor of psychiatry and director of the Anxiety Disorders Clinic at the University of Oklahoma Health Sciences Center in Oklahoma City.

“These people assume they're OK, but you have to look at other things like what their hearts are doing to see the health consequences,” said Tucker in an interview with Psychiatric News.

“This study shows that traumatic events are not simply psychological in nature but also have physiological consequences,” said Frank Putnam, M.D., a professor of pediatrics and psychiatry and director of the Mayerson Center for Safe and Healthy Children at the Cincinnati Children's Hospital Medical Center, in an interview. “The body is still keeping score even though they think they've moved on.”

Half the people in the Alfred P. Murrah Federal Building were killed by the explosion, and many of the rest were injured. Tucker was on duty that April 19, when Timothy McVeigh set off the bomb in downtown Oklahoma City, and helped treat survivors at the local Veterans Affairs hospital.

Tucker and her colleagues evaluated 60 survivors out of a group of 113 who had been studied shortly after the event by Tucker's co-author Carol North, M.D., M.P.E., now a professor of psychiatry at the University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center in Dallas. Besides not using cardiovascular or psychiatric medications, the subjects in the current study could have no untreated or unstable medical illness that might have biased physiological measurements. Among those survivors meeting the selection criteria, 84 percent had been injured in the blast, and 27 percent of them required hospitalization. About 96 percent said they had recovered or nearly recovered from any effects of the bombing.

Tucker, North, and colleagues compared these 60 with an equal number of age- and gender-matched individuals in the Oklahoma City area who were not near the explosion, did not have friends or relatives at the site, and weren't involved in rescue or recovery efforts.

The researchers measured heart rate and systolic, diastolic, and mean arterial blood pressure in each subject before, during, and after a semistructured interview about the bombing. Next, they administered four psychometric tests to evaluate posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) symptoms: the DSM-IV version of the Diagnostic Interview Schedule (DIS), the DIS Disaster Supplement Interview and Questionnaire, the Beck Depressive Inventory, and the Impact of Event Scale–Revised.

“While some findings have been identified before, this study benefits from being a fairly large sample of a resilient, nonclinical population who experienced a single, well-defined event and follow-up period,” said Putnam.

Nine of the survivors and one of the control subjects had current PTSD. Seven other survivors had PTSD and comorbid symptoms. Overall, more psychiatric symptoms were found among the survivors than the controls, wrote the researchers in the February American Journal of Psychiatry, but“ survivors nonetheless had low levels of PTSD symptoms and a low rate of PTSD diagnosis, which suggests they either were resilient or had experienced emotional healing over time.”

Both groups of subjects had similar baseline blood-pressure readings, although the survivors had higher pretest heart rates (72.89 beats per minute on average) than the comparison group (68.20). Both of these measures rose significantly for survivors during the discussion of the bombing incident. Their reaction was independent of their PTSD symptoms.

“These results suggest that the residue of trauma exposure may persist less in narrative ratings of emotional effects than in physiologic differences that may be independent of the pathophysiology of PTSD,” the researchers said.

“Tucker and colleagues have added to the literature on the physiologic burden carried by those with PTSD and perhaps also those exposed to extreme trauma who do not reach diagnostic levels,” Robert Ursano, M.D., told Psychiatric News. Ursano is a professor and chair of the Department of Psychiatry and director of the Center for the Study of Traumatic Stress at the Uniformed Services University of the Health Sciences in Bethesda, Md.

“Other studies that related long-term PTSD to increased risk of cardiac disease and stroke also continue to indicate the need for further study of the long-term health burden of severe traumatic events across the health, illness, and disease spectrum,” he said.

Tucker hopes to continue following her subjects. The physiological effects she has observed may harm or help the survivors, she said. Some, especially those with incipient cardiovascular problems, might someday feel the effects that Ursano suggested. Others might find that their heightened reactivity could help them avoid or survive future dangers, said Tucker.

“We have to remember, these exaggerated responses are not just occurring in the lab but also in daily life, prompted by reminders,” said Putnam. “Traumatic events ought to be part of their medical history.” ▪