Data Help Identify Vets Who Need MH Care

The youngest veterans of the wars in Iraq and A fghanistan are more likely to be diagnosed with a mental health problem than their older comrades in arms, according to a new study of over 100,000 discharged vets seen in Veterans Affairs (VA) clinics. Overall, 1 in 4 of all these U.S. veterans received at least one mental health diagnosis, wrote Karen Seal, M.D., M.P.H., of the San Francisco VA Medical Center and an assistant clinical professor of medicine at UCSF, and colleagues, in the March 12 Archives of Internal Medicine.

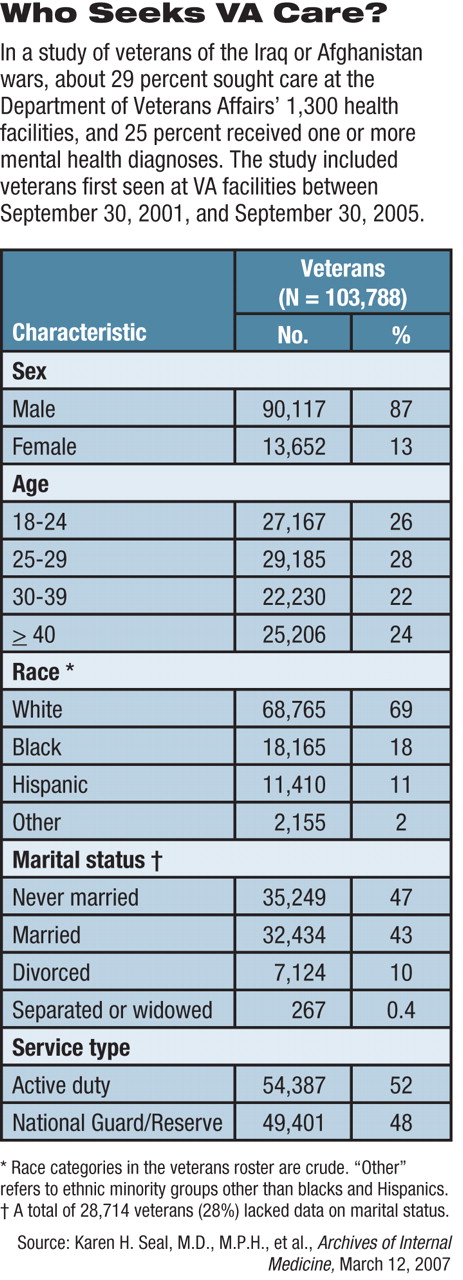

The study examined records from 103,788 veterans who had left the armed forces after September 30, 2001, when the U.S. invasion of Afghanistan began, and made an initial visit to a VA health facility between then and September 30, 2005. Follow-up data were available through December 31, 2005.

That 100,000-plus number of veterans represents about 29 percent of all veterans of the current wars discharged during that time. Roughly half of all the troops had served in the regular, full-time, active duty forces, and half came from activated National Guard or Reserve units (see table).

All visits to any of the approximately 1,300 VA health facilities produce an electronic record, creating the study's administrative dataset. Some selection bias may have occurred, since veterans without medical or psychological complaints were less likely to seek treatment at a VA center, Seal told Psychiatric News in an interview.

“Some veterans may be getting health care elsewhere than at the VA, or not at all,” she said. The VA has not yet conducted a random probability sample covering all returned veterans, she said. Other research indicates that those coming to the VA are in worse shape than veterans who do not, said Robert Rosenheck, M.D., a professor of psychiatry and epidemiology and public health at the Yale School of Medicine.

“Primary care doctors are the foot soldiers for mental health in the VA.”

“Veterans who come to VA medical centers have more mental health problems than vets who don't,” said Rosenheck, in an interview.“ In studies of Vietnam veterans, we found that those who used VA services had had more serious PTSD than nonusers of VA services.”

For instance, he said, 6 percent of veterans who used private insurance received a mental health diagnosis, compared with 25 percent in this group of veterans.

Out of the 103,788 veterans, 25,658 (25 percent) received at least one mental health diagnosis. Posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) was the most common, observed in 52 percent of those with mental health diagnoses, or 13 percent of the veterans included in the study. Diagnoses were encoded using the International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision, Clinical Modification (ICD-9-CM).

If broadened beyond mental disorder diagnoses to include psychosocial or behavioral problems such as relational, occupational, or academic dif ficulties (usually designated as V codes), then 31 percent could be said to have mental health problems.

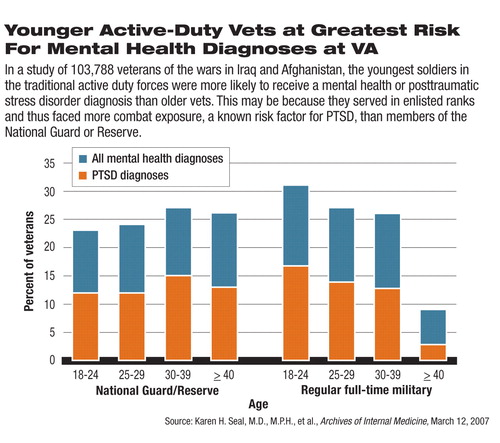

Risk for being given a mental health diagnosis varied little in relation to demographic factors, except for age. Younger veterans—18 to 24 years old—had a significantly higher risk than troops over age 40.

“The highest risk [occurred] in the youngest white male active duty veterans followed by the youngest black male veterans,” wrote the authors. Younger white men were almost five times more likely to have at least one mental health diagnosis and nine times more likely to be diagnosed with PTSD than their older counterparts. However, all white troops in their 20s or 30s displayed some increased risk. The difference was not so extreme among black troops. Black veterans under 40 were two or three times more likely to have a mental health or PTSD diagnosis than their older peers.

The data available to the researchers did not include rank or combat exposure, said Seal. She used age as a marker, assuming that younger troops were of lower rank and more likely to experience combat. Combat exposure is associated with higher rates of PTSD.

In the new VA study, 60 percent of the veterans with mental health disorders were diagnosed in VA settings other than specialty care, mainly in primary care clinics. Out of that group, 61 percent were referred for mental health visits, where 92 percent of those had their initial mental health diagnosis confirmed.

“It bodes well that the diagnoses were so frequently confirmed. Primary care doctors are the foot soldiers for mental health in the VA,” said APA Trustee Mary Helen Davis, M.D., a private practitioner in Louisville, Ky., and chair of APA's Ad Hoc Work Group on Veterans Affairs and Military Initiatives. “Often astute primary care doctors pick up on mood changes, anxiety, sleep patterns, or somatic manifestations.”

The study's findings should help both VA and civilian health officials plan for the needs of these veterans, said Davis. “The higher medical and mental health needs of these veterans have the potential to overwhelm the VA system.”

Davis's ad hoc work group has submitted a proposal to the APA Board of Trustees to support improved access to mental health and substance abuse services for returning military personnel and their families. The report also calls for increased funding for research on evidence-based treatment of PTSD and other war-related health consequences, traumatic brain injuries and their long-term effects on health, mental health needs of women in the military, and programs that help reduce the stigma of seeking mental health and substance use services.

“The consequences of the Iraq and Afghanistan wars are a national public health crisis,” stated the ad hoc work group's report. “It is essential that the federal government and the medical, mental health, and patient advocacy communities work together to expand our knowledge of war-related trauma and to ensure that military families have timely access to quality services.”

The VA study's findings should direct attention to the youngest members of the armed services, said Seal and colleagues. “Early detection and evidence-based treatment in both VA and non-VA mental health and primary care settings is critical in the prevention of chronic mental illness, which threatens to bring the war back home as a costly personal and public health burden.”

The VA researchers' next steps will include following this same cohort to document any changes in the rate of mental health diagnoses and health utilization patterns in the VA, according to Seal. They are also planning a randomized, controlled trial on an intervention known as “motivational interviewing” to see whether it will lead Iraq and Afghanistan veterans who screen positive for PTSD, alcohol or substance abuse, or depression to enter mental health treatment.

An abstract of “Bringing the War Back Home” is posted at<http://archinte.ama-assn.org/cgi/content/abstract/167/5/476>.▪