How Successful Is Mass. Insurance Reform Effort?

Two years after the Massachusetts health care financing system was signed into law, its supporters say it has had enough success to provide important guideposts for other states considering expanded health care access, if not a national health financing program.

The law, known as Chapter 58, was enacted in spring 2006 and has rolled out additional features—such as penalties for failure to obtain individual insurance—since then. The goal of the program was to reduce the number of uninsured in the state as much as possible below the 10 percent of the state's population that was then uninsured.

Supporters say the program has gone “reasonably well,” with 340,000 newly insured as of January 1, which is about 70 percent of the adult uninsured population, according to John Kingsdale, executive director of the Commonwealth Health Insurance Connector Authority. Kingsdale and other policy experts with knowledge of the program discussed it during a meeting with congressional staff in May.

The expansion in insurance coverage included about 110,000 individuals newly insured by commercial private insurance plans that are unsubsidized by the state. Among the keys to that growth were changes in the“ nongroup,” or individual, insurance market to require virtually the same coverage terms as are common in the group-insurance market and the same guaranteed policy renewal—so benefits cannot be cancelled at the first occurrence of major illness.

“In Massachusetts, we have actually been able to make this nongroup market...function,” Kingsdale said.

Other accomplishments include reductions in the number of people seeking free care at the state's “safety net” hospitals and reductions in the amount spent on such care by most hospitals. In the last two years, for example, spending on free care at Brigham and Women's and Massachusetts General hospitals dropped by 17 percent.

The new system also has encouraged broad employer participation in providing health insurance for their workers. The law included an annual penalty of $295 per worker for businesses with 11 or more employees who did not contribute to health coverage for their workers. The approach has resulted in 72 percent of Massachusetts employers providing insurance, as opposed to 60 percent nationally, according to Kingsdale. Similar drops in free care were seen at the state's community health centers.

The new law also expanded Massachusetts' State Children's Health Insurance Program (SCHIP)—a state and federal partnership that provides health coverage for children in low-income families—to include children from families with incomes of up to 300 percent of the federal poverty level. The change raised eligibility for the free insurance to include minors from families with incomes of up to nearly $64,000 for a family of four, for example.

About 175,000 low- and moderate-income adults received coverage through Commonwealth Care, the new state program that offers free or heavily subsidized coverage for people with incomes up to three times the federal poverty level. In addition, the state expanded Medicaid eligibility and added about 7,000 new Medicaid enrollees.

Another accomplishment of the law was the establishment of a new state entity called the Connector, which provides an online menu of available private health insurance plans that meet basic standards set by the state. The Web site allows individual insurance customers to perform“ apples-to-apples” comparisons of the major insurance plans available and purchase them through the Web site. This feature “is thoroughly radical and unprecedented, believe it or not, in terms of what you have to go through as a consumer to get health insurance,” said John McDonough, executive director of Healthcare for All, a consumer advocacy group in Massachusetts.

Major Hurdles Remain

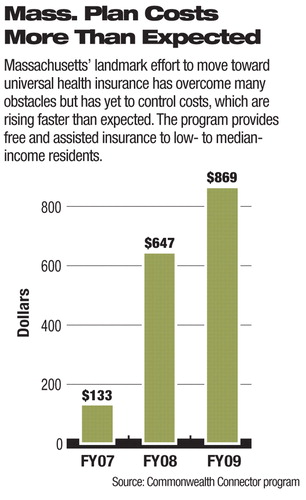

Among the challenges for the Massachusetts financing system is the steadily growing cost of the program. The state predicts the program will cost about 10 percent more than previously estimated for the next fiscal year, creating a budget gap of about $150 million.

The main cost driver, critics and supporters agree, is that there were many more low-income people in need of coverage than the state estimated. Among the 330,000 Massachusetts residents that are newly insured, at least 263,000 are in free or subsidized plans.

“So it shows you again the heavy lift of expanding access to health insurance, especially when the taxpayer is paying a large part of the bill,” said Grace-Marie Turner, president of the Galen Institute, a forum for market-based ideas to reform health care financing.

Supporters acknowledge that the increasing cost is a problem but emphasize some cost-containment victories, such as keeping the annualized rate of increase at 6.5 percent, as originally projected.

That cost to taxpayers may sharply increase, supporters acknowledge, as more low-income residents who work for employers that provide insurance realize they are eligible to switch to better, state-subsidized insurance under the law. Massachusetts officials estimate that if all who are eligible switch over, it could cost the state billions more by 2012.

Some State Residents Critical

The cost of coverage for individuals who make too much to qualify for state assistance also has generated heavy criticism from some residents, who are mandated to buy insurance or face escalating penalties. It's inappropriate and maybe impossible for a state entity to determine what amount of insurance is affordable or appropriate for a family, Turner said, and the lowest-cost insurance options are still considered too expensive by many residents.

Kingsdale acknowledged the difficulty in finding the proper affordability levels but stressed the fundamental importance to the entire health care financing system of an individual insurance mandate.

“We do live in a society where when you step off the curve and you get hit by a bus—to use that proverbial example—you do expect to be picked up by an ambulance, taken to an emergency room, and treated in the ICU if necessary.” Such care, he said, can amount to hundreds of thousands of dollars that someone other than the individual needs to pay.

Key Lessons Learned

The Massachusetts system has many shortcomings and will need improvements for many years to come, according to supporters. However, its many successes and even its shortcomings offer valuable lessons to other states and the nation in trying to create broad-based access to health care. Its success so far is rooted in the political alliance that created it. As long as a broad coalition of health care providers, employers, citizens, and politicians continue to support trying to maintain and improve the system, then it will thrive.

Another key to program success, supporters discovered, was to create an electronic application system that was simple and straightforward, did not involve much paperwork, and put the burden on regulators—not the public—to correct problems or delays in the process.

More information on the congressional roundtable on the Massachusetts health plan is posted at<www.allhealth.org/briefing_detail.asp?bi=128>.▪