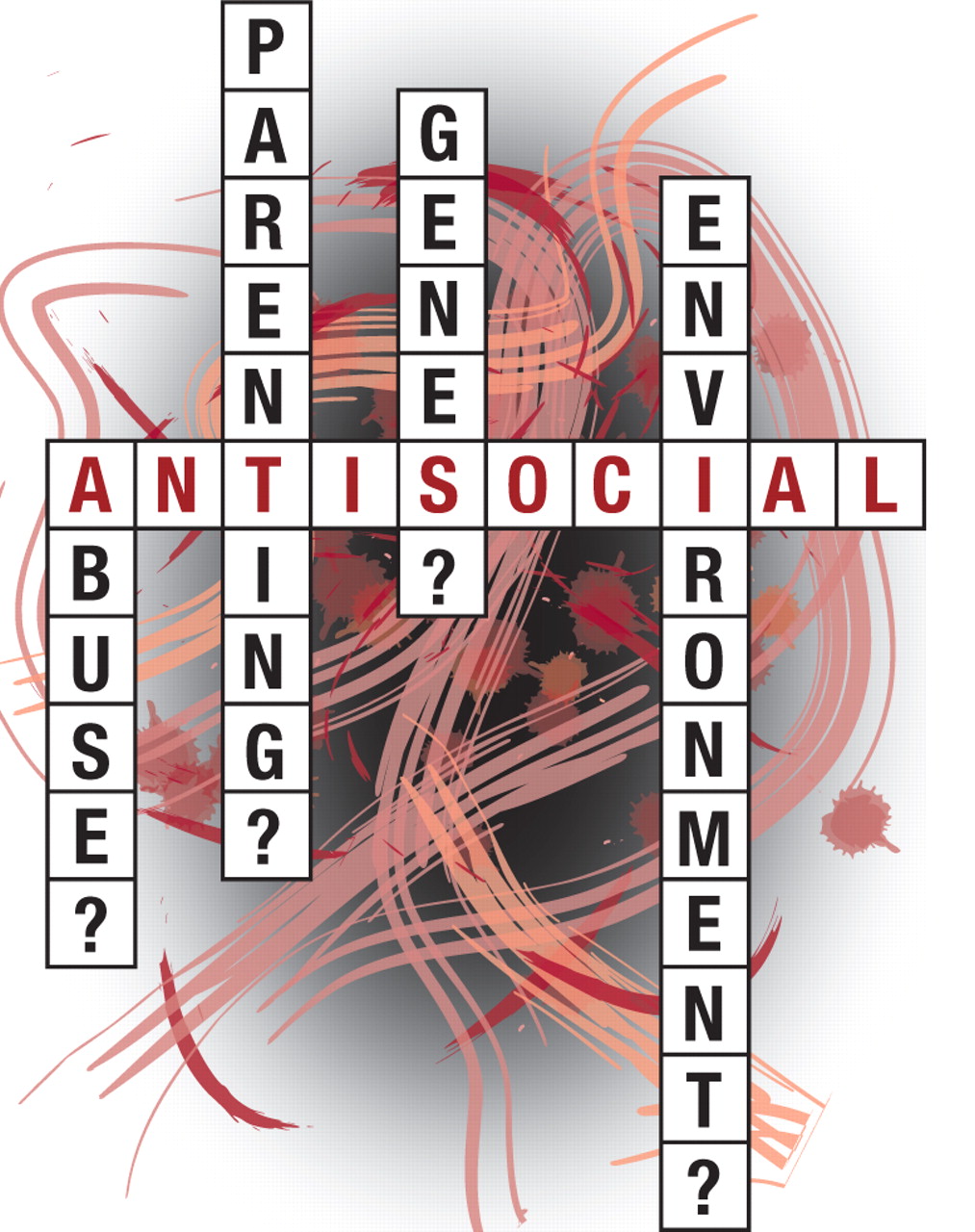

Multiple Factors at Root of Antisocial Behavior

Antisocial behaviors, as psychiatrists know well, can run the gamut from lying, stealing, and manipulating to torturing and killing. Furthermore, antisocial behaviors often show up as early as adolescence or even childhood. For example, three children in Georgia had worked out an elaborate plan to kill their teacher before they were caught, ABC Evening News reported on April 2.

But what is it that propels youngsters toward antisocial behavior? Various researchers have been looking into the question; there are a number of associated factors, it appears.

One is maternal smoking during pregnancy. It has been linked to antisocial behaviors in offspring, even when possibly confounding factors such as mothers being unmarried, uneducated, or antisocial were considered (Psychiatric News, January 18, 2002; May 19, 2006).

Another is head injury. Michael Stone, M.D., a professor of clinical psychiatry at Columbia University and a forensic psychiatrist, has interviewed or read in-depth biographies of 145 serial killers. About a fourth of them experienced protracted periods of unconsciousness from head injury during childhood or early adolescence, he said in an interview with Psychiatric News.

Michael Stone, M.D.: “When I interviewed Tommy Sells on death row in Texas last year, he told me that he felt that his early years had contributed tremendously to who he had become.”

Credit: Joan Arehart-Treichel

Abuse appears to be still a third contributor to antisocial behaviors. Boys who experience abuse have been found to be at risk of conduct disorder, antisocial personality symptoms, and becoming violent offenders. Indeed, the earlier children experience abuse, the more likely they are to develop these problems. Also, serial killers often come from “horrific backgrounds, where they were brutalized by one or both parents,” Stone has found. Take the case of serial killer Tommy Sells. “When I interviewed Tommy on death row in Texas last year, he told me that he felt that his early years had contributed tremendously to who he had become,” Stone said.

Specifically, when Sells was a child, his mother had abandoned him to the care of an aunt, and the aunt in turn had given him to a pedophile who sexually abused him, Stone explained. These experiences filled Sells with“ a volcanic hatred” for those three people and also prompted him to seek revenge against people who resembled them, Stone said. “He would slip into homes and slit the throats of young women, and when he saw somebody he thought was abusing a child, he killed that person.” (The article Original article: Can Antisocial Behaviors Be Prevented? discusses a program that aims to alter factors that may put children at risk of engaging in antisocial behaviors.)

Inconsistent Discipline a Risk Factor

In addition to being abused, inconsistent discipline and lack of supervision have been found to be associated with development of antisocial behaviors in young people, Tanya Button, Ph.D., a postdoctoral fellow at the University of Colorado's Institute for Behavioral Genetics, told Psychiatric News. Along with Peter McGuffin, M.D., Ph.D., director of the Institute of Psychiatry in London, Button is researching the causes of antisocial behavior.

The environment outside of the family may contribute to antisocial behaviors too. Affiliating with deviant peers, witnessing violence in the neighborhood, learning about violence via the media—all these have been found to predispose some youngsters to antisocial behaviors, Button said.

In addition, a lack of friends appears to be linked with antisocial behaviors. For example, “The majority of serial killers are schizoid—loners, unable to enter into relationships,” Stone reported. “In fact, the number of serial killers who have schizoid personalities is about 50 times the public average, which is 1 percent.”

Which brings up the question: is having a schizoid personality heritable? Quite possibly, Stone suspects. In any event, not just environmental factors, but some genetic ones have been implicated in antisocial behaviors.

MAOA Gene Implicated

For example, in a twins study, S. Alexandra Burt, Ph.D., a researcher at Michigan State University, found that one type of antisocial behavior—physical aggression—is inherited to a greater degree than rulebreaking, another type of antisocial behavior. Other investigators have come up with similar findings, she said in an interview.

Moreover, a handful of genes have been identified that seem to be linked to antisocial behaviors, Button noted. One of these genes manufactures a transporter for the neurotransmitter dopamine. A second manufactures a receptor for it. A third makes a transporter for the neurotransmitter serotonin. Two more make receptors for serotonin. Three other genes implicated in antisocial behaviors manufacture enzymes. The first makes the enzyme tryptophan hydroxylase. The second makes the enzyme catechol-o-methyltransferase (COMT). The third makes the enzyme monoamine oxidase (MAOA).

The gene most strongly implicated in antisocial behaviors is the gene that makes MAOA, located on the X chromosome. MAOA breaks down the neurotransmitters dopamine, norepinephrine, and serotonin, rendering them inactive. A long version of the gene produces a lot of enzyme activity, a short version of the gene produces little. And deficiencies in the MAOA gene have been linked with aggression in both mice and humans.

Increased aggression was observed in mice in which the entire MAOA gene was deleted; the aggression abated upon restoration of the gene. Five men in a particular family who engaged in antisocial behaviors such as arson, exhibitionism, and attempted rape were found to lack the MAOA gene, according to a study reported in the October 22, 1993, Science.

So Avshalom Caspi, Ph.D., a professor of developmental psychiatry research at the Institute of Psychiatry in London, and his colleagues wondered why all children who are abused don't grow up to engage in antisocial behaviors? Could it be that those who do, do so not just because they have been abused, but because they possess the short MAOA gene variant? In their landmark study to find out, they genotyped more than 1,000 boys for either the long or short version of the MAOA gene, assessed the boys for abuse while they were young, and then followed them to adulthood to see whether any pursued antisocial behavior. Finally they looked to see whether the MAOA gene version that maltreated boys possessed was linked to whether they engaged in antisocial behaviors.

There was such a link Caspi and his team reported in the August 2, 2002, Science. While boys who had been abused and had the short gene variant constituted only 12 percent of the entire cohort, they accounted for 44 percent of the cohort's convictions for violent acts. Furthermore, of the boys who had been severely abused and who possessed the short gene variant, 85 percent engaged in some form of antisocial behavior.

Debra Foley, Ph.D., an assistant professor of human genetics at Virginia Commonwealth University, and coworkers published comparable results in 2004. So did Kent Nilsson, a doctoral candidate at Uppsala University in Sweden, and colleagues in 2005.

Yet if abuse and the short MAOA gene variant can conspire to trigger antisocial behaviors, does one have a stronger influence than the other? Apparently abuse does, because Nilsson and his group found that abuse predicted antisocial behaviors even when the short MAOA gene variant was not present.

Indeed other environment-gene interactions besides the one between the MAOA gene and abuse probably influence antisocial behaviors. For example, Mark Feinberg, Ph.D., of Pennsylvania State University, and coworkers reported in the April 2007, Archives of General Psychiatry that heritability influences antisocial behaviors more when parenting is negative and cold than when it is positive and warm. In this case, no specific genes were identified, since it was a behavioral genetics study, not a molecular genetics one.

Based on Feinberg's conclusion, the larger question becomes which has a stronger influence on antisocial behaviors—genes or environment?

“I think that there is evidence that the contribution of environment to antisocial behavior is larger than that of genetic factors,” Frank Verhulst, M.D., a child psychiatrist at Erasmus University in the Netherlands, told Psychiatric News.

Burt, however, disagreed: “Behavioral-genetics work to date suggests both. It is really a combination of the two.”

Button concurred with Burt: “In studies of heritability, the proportion of the variance of antisocial behavior that can be attributed to genetic effects is 50 percent, and the other 50 percent is explained by environmental influences.... Consequently, it is not possible to conclude that either genes or environment contribute more to antisocial behavior. Both are integral to its development.”

Stone, in contrast, maintains that “it is futile and silly to state either that genetic influences are stronger or that environmental factors are.... This is because the situation needs to be examined on a case-by-case basis.”

In any event, coming from an abusive home seems to be the most common contributor to antisocial behaviors, Stone noted, and it carries a compelling take-home message, he believes: “If you beat the heck out of your child, you're pushing him or her in the direction of becoming antisocial.”▪