State Insurance Mandates Often Omit MH Coverage

As states take the lead in expanding health care access for more Americans, mental health advocates worry that people with psychiatric conditions and substance use disorders are being left behind.

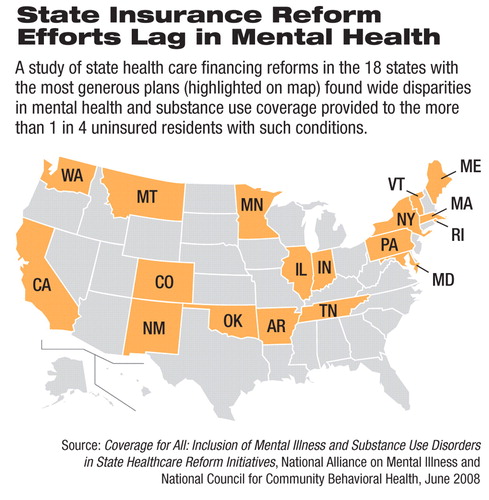

Their concerns stem from a report released in June on the mental health components of health insurance plans from the 18 states (see map) with the most generous health care coverage programs or plans.

The report, by the National Alliance on Mental Illness (NAMI) and the National Council for Community Behavioral Healthcare (National Council), is titled “Coverage for All: Inclusion of Mental Illness and Substance Use Disorders in State Healthcare Reform Initiatives.”

The report examined the Medicaid programs, state health care coverage laws, and insurance expansion proposals in 18 states to quantify the extent to which treatment for people with mental illness, including substance use problems, is covered.

According to the report, about 60 percent—or 11 of the 18 states studied—provide at least one insurance plan with equal coverage for mental illness among their programs and proposed plans for the uninsured. Seven of these states did not provide at least one mental health parity option, but had preexisting parity statutes governing only private insurance plans—not the state-funded programs. Coverage for substance use disorders was even poorer. Only 28 percent of the state reform plans studied offered at least one insurance plan with parity coverage for substance use disorders. Just five of the 18 states—Colorado, Indiana, Maine, Minnesota, and Vermont—had parity coverage for substance use disorders in at least one of their programs or proposals for the uninsured.

The impact of the coverage shortfall could be significant, as the report concluded that more than 25 percent of adult Americans who lack insurance coverage have a mental illness, substance use disorder, or co-occurring disorders.

“Many states are trying to cover the uninsured but need to do more in these critical areas that affect 1 in 4 Americans,” said Michael Fitzpatrick, NAMI's executive director.

The report also said that states that provide less than a parity benefit for substance use disorders impose a variety of service limits, including caps on outpatient treatment visits, limitations on inpatient stays, and maximum dollar limits.

States generally viewed as closest to achieving universal coverage, according to the report, were more likely to provide mental health parity as a component of their health care reform effort. For example, Maine and Vermont include equal benefits for mental illness and substance use disorders and other health conditions in their health insurance programs. Massachusetts provides equal coverage for serious mental illness, co-occurring disorders, and physical health conditions, while coverage for the treatment for alcoholism must meet minimum standards mandated by state law.

About 90 percent of the programs in the eight states that have proposed or implemented health insurance coverage programs for residents of all incomes require mental health parity for serious mental illness or for a broader category of mental illness.

Serious mental illness is also referred to in some states as“ biologically based” mental illness, according to the report. It typically includes schizophrenia and other psychotic disorders, bipolar disorder, major depressive disorder, obsessive–compulsive disorder, and panic disorder.

About 40 percent of these states provide parity for treatment of substance use disorders.

“We can effectively treat substance use disorders and mental illnesses, and people [who] suffer from these debilitating conditions deserve treatment,” said Linda Rosenberg, president and CEO of the National Council. “It is distressing that there are insurance plans and health care reform initiatives that continue to discriminate.”

Even among the state plans that include parity mental health benefits, the report noted that copayments are increasing, which is a trend throughout health care plans. Most programs have “significant” copayments, including those targeting low-income and small-employer populations.

Only Minnesota exempts outpatient mental health and substance use services from copayments to remove a financial barrier to accessing these services.

Medicaid plans and a few other state programs have very low or no copayments, though most states are charging more per visit or prescription.

Few state reform plans for the uninsured, according to the report, include efforts to address workforce shortages in mental health and substance use, chronic-care management of these conditions, or wellness benefits for these conditions.

“Basic parity is not enough,” Rosenberg said. “More states need to address problems with scope of benefits, copayments, prior approvals, and shortages of mental health professionals.”

Among the exceptions to states lacking parity for mental illness prevention measures is Indiana. In addition, Vermont's program for the uninsured and Illinois's health care reform proposal, as well as the Illinois Medicaid program, include mental illness and substance use disorders in their case-management programs.

The National Council report found that federal waivers allowing Medicaid expansions have been a component of reform in approximately 75 percent of states with implemented programs, which highlights the importance of federal policy in future state health care reform efforts.

Although states with various levels of mental health and substance use benefits have been granted federal waivers to expand the eligible population for Medicaid coverage, the programs with the broadest array of services and those closest to universal coverage receive additional federal funds through waivers from the federal government. The widespread use of federal waivers to expand state Medicaid programs underscores the reliance on federal funds for state health care expansion, according to the authors, and the influence of the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services' policy of furthering health care reform.

The authors of the report cited a need for a federal parity mandate. They concluded that proposed legislative restrictions on federal waiver financing also will have a negative impact on the ability of states to move toward universal coverage.

The report is posted at<www.HealthcareforUninsured.org>.▪