Is Hispanics' Depression Outcome Affected by Language Choice?

English-speaking Hispanic participants in a major clinical trial responded better to antidepressant treatment than did their Spanish-speaking peers, but language preference is probably a marker for other medical and social factors, said a report in the November Psychiatric Services.

The study, a secondary analysis of the STAR*D study of depression treatments, points to the need for culturally informed approaches to psychiatric diagnosis and care, said Andres Pumariega, M.D., chair of the Department of Psychiatry at the Reading Hospital and Medical Center in Reading, Pa., who was not involved in the report.

“Psychiatrists and primary care physicians need training in a culturally specific understanding of illness, its cultural expression, and the signs and symptoms of illness for the population we are serving,” said Pumariega, chair of APA's Committee of Hispanic Psychiatrists.

In the STAR*D study, researchers led by Ira Lesser, M.D., chair of psychiatry at Harbor-UCLA Medical Center in Los Angeles, sought to find out if Hispanic patients with major depressive disorder who preferred communicating in Spanish (n=74) differed in illness severity or response patterns compared with Hispanic patients who preferred speaking in English (n=121). The participants all were enrolled in the trial from two Southern California treatment sites and accounted for 60 percent of the Hispanics in the STAR*D trial.

Research coordinators who were both bilingual and bicultural assessed participants choosing Spanish, and bilingual and bicultural physicians managed their treatment with the antidepressant citalopram.

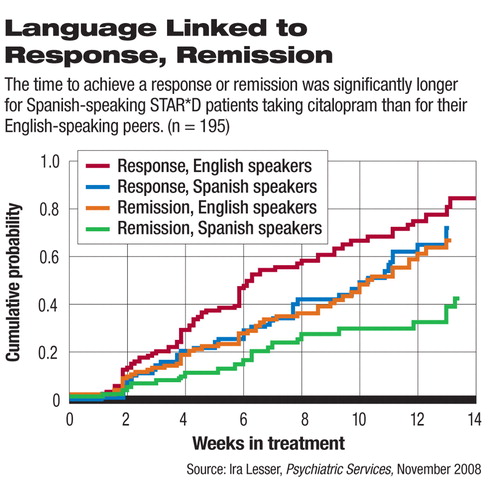

Before adjustment of confounding variables, the Spanish speakers were less likely to achieve remission and took longer to get there, wrote Lesser and colleagues. However, adjustment for demographic, clinical, functional, and severity variables eliminated those differences, indicating that those factors may be just the ones standing in the way of better outcomes for these patients, they said.

“[T]he poorer response by Spanish speakers may be related to factors such as their more disadvantaged socioeconomic status or higher medical burden, rather than their language preference per se,” wrote the authors.

The Spanish speakers tended to be older and less educated than their counterparts who preferred using English, with lower incomes and a first major depressive episode occurring later in life.

“These baseline differences are consistent with what we know about Latinos with mental illness” who prefer to speak Spanish, said Pumariega. “They have more socioeconomic and medical illness burdens, but also show more chronicity of mental illness and a longer time to seeking treatment.”

Part of that disparity may be due not only to socioeconomic issues but to a preference among Latinos for obtaining mental health care from primary care providers, who ordinarily know less about mental illnesses than specialists do, said Pumariega.

“Primary care physicians do not have the same skills as psychiatrists in diagnosing and treating depression, leading to a less-skilled approach to management of depression and possibly contributing to some disparities of outcomes,” he said.

Furthermore, a preference for primary care may have deep cultural roots. Among some Latinos, especially the less educated and the more recent arrivals in the United States, there is an added burden of stigma in seeking help, based on experiences in their ancestral countries. To them, seeing a psychiatrist is just the first step on a slippery slope to institutionalization, said Pumariega.

Another issue is the variation of subcultures collected under the single umbrella labeled “Hispanic” or “Latino.” “A Cuban-American psychiatrist may well miss the meaning and context of a Mexican-American's story,” said Pumariega.

Finally, many clinical trials may contain a subtle, invisible barrier despite all attempts to bridge the gap between researcher and subject, he said.

“It is assumed that Latinos have a clear conception of what depression means to the interviewer or psychiatrist,” he said. “If they used culturally specific Spanish-language terms, the responses may have been different. You have to use terminology they use, not what is used in mainstream culture.”

“Depression Outcomes of Spanish- and English-Speaking Hispanic Outpatients in STAR*D” is posted at<http://ps.psychiatryonline.org/cgi/content/full/59/11/1273>.▪