Published Clinical-Trial Data Give Incomplete Picture

The published medical literature on antidepressants is missing a large proportion of industry-sponsored clinical trials in which the active drug did not beat placebo in a blinded, controlled trial, a study published in the January 17 New England Journal of Medicine shows.

This publication bias hinders realistic assessment of the drug class and could have exaggerated the efficacy of these medications.

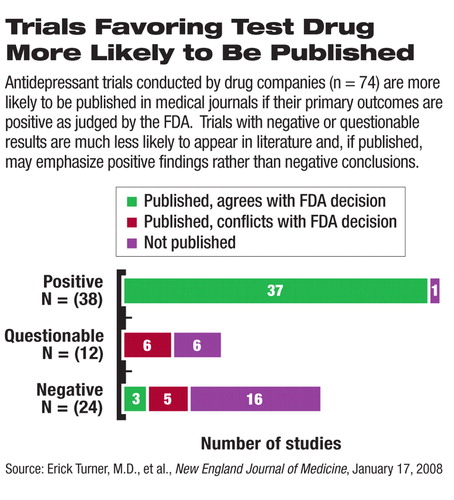

The authors, led by Erick Turner, M.D., an assistant professor of psychiatry and pharmacology at Oregon Health and Science University, compared industry-sponsored clinical trials that have been published in biomedical journals with those that have been submitted to the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) as required for all currently marketed antidepressants. About half (38) of the 74 clinical trials submitted to the FDA were deemed by the agency to have positive results (that is, the primary endpoints, defined before the trial initiation, were met). The authors classified study results as positive or negative on the basis of the FDA reviewers' judgment. A questionable study was one that the FDA judged to be neither positive nor clearly negative.

Almost all (37 of 38) of the positive studies were published in scientific journals. In contrast, only three of 36 studies with results that were judged negative or questionable were published as negative studies. Eleven of these negative or questionable studies were published in a way that made the outcomes, in the authors' opinion, appear positive, and the rest (22 studies) were not published at all.

To measure the consequences of this publication bias, the authors calculated the effect size—an estimation of clinical impact rather than statistical significance—based on data from the 51 published trials and from all 74 trials.

Not surprisingly, the effect size from the published trials came out larger than that from all the trials, making the drugs' efficacy look greater than the total data would support.

The authors acknowledged that their findings do not mean that antidepressants are not efficacious. After all, the FDA had reviewed and analyzed all the published and unpublished study data and approved each drug for marketing. Meta-analysis by the authors also found each antidepressant to be superior to placebo. Rather, the authors asserted that selective reporting of trial data in the medical literature “deprives researchers of the accurate data they need to estimate effect size realistically” and in turn may “lead doctors to make inappropriate prescribing decisions.”

Calls for Reporting Transparency

Selective publication of industry-sponsored clinical trials is not a new phenomenon or limited to psychiatry, APA President Carolyn Robinowitz, M.D., pointed out in a press release. She reiterated APA's official position of supporting mandatory open access to all clinical-trial data.

“Organized psychiatry has actually been in the forefront of trying to address this issue,” said David Fassler, M.D., a clinical professor of psychiatry at the University of Vermont. He cited APA's role in pushing the AMA to issue a comprehensive report on publication bias and calling for a centralized, publicly accessible registry of all clinical trials in 2003.

“Studies with negative outcomes are either less likely to be submitted or they're rejected during the review process,” observed Fassler, who is an APA trustee-at-large. The International Committee of Medical Journal Editors (ICMJE), representing 12 major international medical journals, echoes this observation. Researchers and journal editors“ typically are less excited about trials that show that a new treatment is inferior to standard treatment and even less interested in trials that are neither clearly positive nor clearly negative, since inconclusive trials will not in themselves change practice,” the ICMJE editors wrote in September 2004.

In response to concerns about publication bias, ICMJE announced that, beginning July 1, 2005, all clinical studies submitted for publication must have been prospectively registered in a free, searchable public registry. This requirement was soon adopted by many other journals, including the American Journal of Psychiatry, rapidly spreading the practice of clinical-trial registration among industry and academic researchers. The ICMJE also urged journals to give more weight to negative studies when choosing papers for publication.

In fall 2007, the U.S. Congress passed the Food and Drug Administration Amendments Act, which contains general provisions for establishing a national, publicly accessible, clinical-trial database. Pharmaceutical companies will be required to register prospectively all phase 2 and phase 3 clinical trials and report “basic results” from clinical trials in the database within one year of trial completion. The results-reporting requirement is limited to approved drugs. The Department of Health and Human Services will set specific rules for this mandate, thus making the reporting of clinical trials a government-regulated activity.

In response to these policies, pharmaceutical companies have begun posting clinical-trial results on the Internet routinely. It is conceivable that in the near future all clinical-trial results of approved drugs will become publicly accessible, even if they are not published in a biomedical journal.

Trial Quality a Problem

The disappointing performance of antidepressants in the unpublished, industry-funded clinical trials reflects poor quality in conducting trials, and the system of “drug approval, publication, and marketing provides clear incentive for the publication of only positive results of clinical trials,” John March, M.D., M.P.H., told Psychiatric News.“ The industry is simply following the rules of normal business practice.”

March is a professor of psychiatry and chief of the Child and Adolescent Psychiatry Division at Duke University Medical Center and a principal investigator in the Treatment for Adolescents With Depression Study (TADS), one of several NIMH-sponsored large clinical trials that assessed the comparative effectiveness of treatments for psychiatric disorders in clinical settings.

The NIMH-sponsored clinical trials in children as well as adults provide a sharp contrast to industry-sponsored studies in many areas: the publicly funded studies directly compared medications with placebo and psychotherapy, allowed enrollment of patients with comorbidities, studied vulnerable populations including young children, applied more rigorous protocols and procedures, and generated data that are open to researchers and the public.

“If you look at antidepressant trials in kids, the response rate to active drug is essentially the same across all the trials at about 60 percent,” said March. He blames high placebo-response rates for the lack of efficacy in many of the unpublished industry trials. “In publicly funded trials that were done at institutions with experienced clinician-researchers, the active groups separated from placebo groups [that is, became statistically significantly different] earlier, and the effectiveness of active treatments was clearly positive,” said March.

He pointed to the differences in the quality of study design and conduct between industry- and NIMH-sponsored pediatric trials of medications for several mental illnesses. The quality of some of these studies may have prevented them from being published in medical journals, a possibility acknowledged by Turner and colleagues.

The rules of regulatory approval and marketing-exclusivity extension reward rapid completion of clinical trials, as long as the drug meets the minimum requirements for statistically beating placebo in two trials. They do not penalize marginally positive results or subpar trial design and conduct.

“A company can spend $40 million on a couple of quick pediatric trials to satisfy the FDA requirement in exchange for a half to one billion dollars of profit in the six-month patent extension,” said March.“ The incentives are all wrong.”

March advocates a nationwide consortium of psychiatric clinicians and researchers who would participate in a network of clinical trials to answer key questions for patient care. “The industry is not likely to do trials that are particularly beneficial to clinicians, particularly head-to-head comparison trials and treatment augmentation trials for partial responders and nonresponders,” he said. “Public health is too important to leave these questions entirely in the hands of the industry.”

An abstract of “Selective Publication of Antidepressant Trials and Its Influence on Apparent Efficacy” is posted at<content.nejm.org/cgi/content/abstract/358/3/252>.▪