Clark Notes Centenary of Historic Freud Visit

Once upon a time, Sigmund Freud came to America.

He walked (in Central Park), he talked (at Clark University).

Then he returned home to Vienna.

While here, he accepted the only honorary degree he would ever receive and retained his jaundiced view of the United States. His influence on the mind and its workings, however, traveled outward from that week in September a hundred years ago to rise and fall in the New World for the next half century.

To mark the centenary of Freud's visit, Clark University has planned two conferences, one from October 3 to 5 and another on November 21. Sophie Freud, granddaughter of Sigmund Freud, is one of the speakers. The New York Academy of Medicine will also commemorate the event with a conference on October 3 and 4.

Jung Helps Persuade Freud

In 1909 Freud's work was known only to a handful of scholars and clinicians on this side of the Atlantic when G. Stanley Hall, the president of Clark, wrote to invite him to join in the commemoration of the university's 20th anniversary. Hall was a major figure in American psychology and an admirer of Freud's work, especially as it applied to sexuality in early childhood.

Freud declined Hall's first invitation, saying that the original July date would interfere with seeing his patients. The Swiss psychiatrist Carl Jung wrote to tell Freud that he was missing an opportunity to draw attention to his ideas on both sides of the Atlantic. Eventually, Hall shifted the conference to early September to accommodate other speakers who had also initially begged off. He also increased Freud's honorarium from $400 to $750 (more than $18,000 in today's dollars) and offered him an honorary degree, as well. The combination was apparently enticing enough.

Freud and Clark saw mutual value in the impending conference, said Robert Tobin, Ph.D., now the Henry J. Leir Chair in Foreign Languages and Cultures at Clark, in an interview.

“Clark was new and appropriated some of the glow from its roster of distinguished speakers and honorees,” said Tobin. “Even at 53, Freud was still not that eminent—Interpretation of Dreams had sold only 600 copies—so the degree served to validate his thinking and possibly bolster his status in Vienna.”

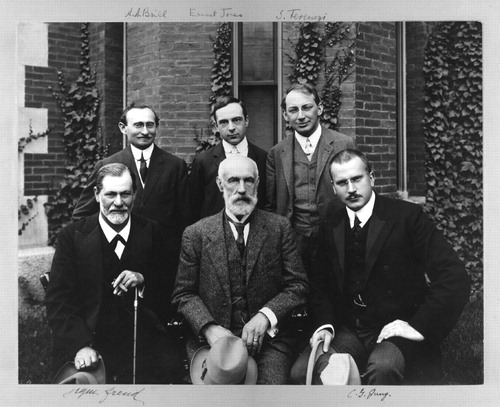

Freud sailed from Bremen accompanied by Jung and the Hungarian psychoanalyst Sandor Ferenczi. Even this humble fact had Freudian overtones. The three had lunch while waiting to embark. When Freud fell ill during the meal, Jung paid the bill, an event that some have interpreted as an oedipal usurpation of the father of psychoanalysis by his chosen heir.

Freud Presents Five Lectures

Freud and Jung spent a few days in New York (and took that stroll through Central Park) before traveling to Worcester, Mass., home of Clark University. Freud arrived on campus on Sunday, September 5, and on Tuesday gave his first lecture, a general outline of the history of psychoanalytic research.

Freud did not read his lectures. His preparation—aside from years of thinking and writing about psychoanalysis—consisted of taking walks with Jung to discuss his intended topics.

He spoke in German. That may not have been an impediment to much of his audience. Clark, Johns Hopkins University, and the University of Chicago were founded around the same time as graduate research institutions based on the German model. Many of those who attended the lectures, including Stanley Hall, had studied in Germany, and German was the primary language of research at the time. Reports of Freud's lectures also appeared in English the next day in the Worcester Telegram.

Freud continued his discussion of the history of psychoanalysis on Wednesday morning. On Thursday morning he addressed the psychopathology of everyday life, as expressed in the slips of tongue and pen. He talked about infant sexuality on Friday and transference and wish fulfillment on Saturday.

He seemed to appreciate the moment, despite his earlier reticence.

“[A]s I stepped out to the platform at Worcester to deliver my Five Lectures upon Psycho-Analysis, it seemed like the realization of some incredible day-dream,” he wrote in 1925. “Psychoanalysis was no longer a product of delusion; it had become a valuable part of reality.”

The talks were ultimately compiled and published as Five Lectures on Psycho-Analysis.

Freud wasn't the only significant figure in town that week. Hall used Clark's 20th anniversary as the focus for several conferences intended to celebrate the university as a major research center. (Clark didn't admit undergraduates until 1902, and then only under pressure from its eponymous patron, Jonas Clark.) Hall organized sessions on biology, chemistry, physics, mathematics, and China and the Far East. A conference on child welfare was held in July.

Physicist Albert Michelson, the first American to win a Nobel Prize in science for his work on measuring the speed of light, British physics Nobelist Ernest Rutherford, and astronomer Percival Lowell were honored with degrees. Leo Baekeland, inventor of the first fully synthetic plastic, attended. Robert Goddard, who later became known as the father of American rocketry, was a grad student at Clark and appears in photographs of the distinguished attendees.

Besides Jung and Ferenczi, other speakers or attendees from the realms of psychiatry and psychology included anthropologist Franz Boas; psychiatrists Adolph Meyer and William Alanson White; neuropathologist James J. Putnam, founder of the American Neurology Association; and Mary Whiton Calkins, the first woman president of the American Psychological Association. The philosopher and psychologist William James came up from Harvard to listen to one of Freud's lectures.

Solomon Carter Fuller, recognized today as the first African-American psychiatrist, attended, too, at the invitation of Clark's biology department. Fuller was a neuropathologist at Westborough State Hospital and was Hall's personal physician for a time. He, too, had spent several years studying in Germany, working part of the time in Alois Alzheimer's lab.

One nonscientist, Emma Goldman, the well-known and widely feared anarchist, a former resident of Worcester, was back in town to speak, although not at Clark. Goldman agreed with Freud that sexuality was central to human development, but thought that sexual expression, not repression, was the source of human creativity, according to Candace Falk, Ph.D., editor and director of the Emma Goldman Papers at the University of California, Berkeley.

“The most important event of our Worcester visit was an address given by Sigmund Freud,” wrote Goldman in her autobiography. “I was deeply impressed by the lucidity of his mind and the simplicity of his delivery. Among the array of professors, looking stiff and important in their university caps and gowns, Sigmund Freud, in ordinary attire, unassuming, almost shrinking, stood out like a giant among pygmies.

“He had aged somewhat since I had heard him in Vienna in 1896. He had been reviled then as a Jew and irresponsible innovator; now he was a world figure; but neither obloquy nor fame had influenced the great man.”

Before returning to Europe, Freud spent a few days after the conference with Putnam at the latter's camp in the Adirondacks. Their interchanges strengthened Putnam's enthusiasm for psychoanalysis, according to articles he wrote in the Journal of Abnormal Psychology.

Ripples from the Clark conference spread, slowly at first, but then became a tidal wave.

“The U.S. was already fertile ground for Freud's ideas,” said Robert Paul, Ph.D., a professor of anthropology and dean of the College of Arts and Sciences at Emory University, in an interview. “The 1909 conference paved the way for the movement from Europe to the U.S. in the 1930s that pushed psychoanalysis to dominate psychiatry until the 1960s.”

Freud's ideas also would change the cultural world, as well, especially following the horrors of World War I, added Tobin. “In the 1920s, intellectuals and artists who wanted to be modern latched onto his ideas, not only about sexuality but also regarding the notion that the mind worked on many different layers.”

Today, we might look back at the conferences with some degree of ambivalence, but they played an important role at the turn of the century in placing Clark on the map in the emerging science of psychology, said Mark Freeman, Ph.D., a professor of psychology at Holy Cross College in Worcester, in an interview. “In addition to the familiar clinical and experimental approaches to psychology, Clark had—and has—an interest in the conceptual, philosophical, and theoretical bases of the field, especially in relationship to developmental psychology.”

“The real value of the 1909 conference was Hall's interest in drawing on a variety of intellectual traditions and disciplines to inspire his campus,” Michael Bamberg, Ph.D., a professor of psychology at Clark, told Psychiatric News. “In selecting his speakers, he was trying things out, looking at innovative trends in emerging disciplines that hadn't made it into the mainstream but were knocking on the door.”

An agenda for Clark University's commemoration of the centennial of Sigmund Freud's lectures is posted at<www.clarku.edu/micro/freudcentennial/conferences/index.cfm>. The New York Academy of Medicine's program is posted at<www.nyam.org/events/?id=448&click=>.▪