Suicide Rates Disappointing Marker of Access to MH Services

Abstract

States have improved overall in recent years in both their provision of needed mental health care for children and in reducing the use of physical restraints in nursing homes, according to an analysis of U.S. health trends.

The findings came from the Commonwealth Fund Commission on a High Performance Health System's second state scorecard report released on October 8. The follow-up report to the 2007 report card uses public-health data to rank states on 38 health indicators in the areas of access, prevention, treatment, avoidable hospital use and costs, and healthy lives. Among its major findings: health insurance coverage for adults declined, health care costs rose, and quality improved in areas in which outcomes were reported to the public.

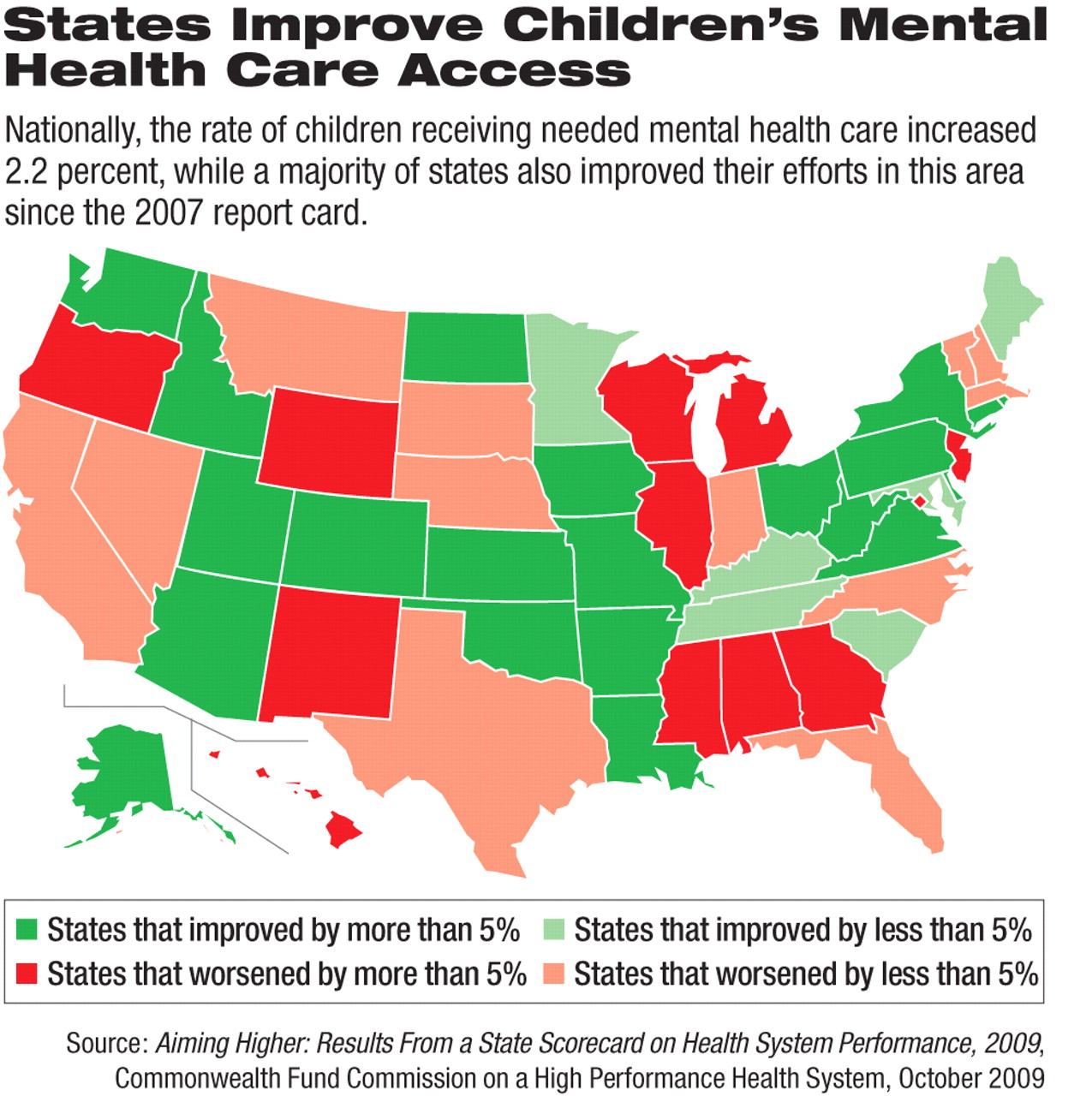

In the few mental health measures that were examined, the report noted that children were slightly more likely to receive needed mental health care, with 27 states improving their standing in this area since the 2007 report. The authors noted that only 21 states “substantially improved” in the rate at which children living there were able to receive needed mental health care, while 11 states and the District of Columbia “declined substantially.”

“Key indicators of nursing-home and home-health-care quality improved substantially in nearly all states, with declines in rates of pressure ulcers, physical restraints, and pain for nursing home residents and improved mobility for home care patients,” wrote the authors.

The decline in the use of restraints came after years of efforts by government health officials and health advocates, including APA, to reduce their use among patients in general and nursing-home residents with mental illnesses in particular.

For example, the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) enacted regulations in February 2007 that sought to minimize the use of seclusion and restraints by physicians and health care workers who treat patients in hospitals that participate in Medicare or Medicaid (Psychiatric News, January 19, 2007).

Although the Commonwealth Fund researchers addressed only physical restraints, the CMS guidelines applied to “any manual method, physical or mechanical device, material, or equipment that immobilizes or reduces the ability of a patient to move his or her arms, legs, body, or head freely; or a drug or medication when it is used as a restriction to manage the patient's behavior or restrict the patient's freedom of movement and is not a standard treatment or dosage for the patient's condition.”

In 2003, APA and other organizations issued a 42-page booklet, “Learning From Each Other: Success Stories and Ideas for Reducing Restraint/Seclusion in Behavioral Health,” which described strategies for reducing the use of seclusion and restraint (Psychiatric News, February 7, 2003).

The Commonwealth Fund researchers began tracking suicide rates in the latest report card as a shorthand method of quantifying the availability of mental health services in the states. Although federal and state funding of mental health services has generally increased in the last decade, the researchers found, the national suicide rate also has increased.

Paula Clayton, M.D., medical director of the American Foundation for Suicide Prevention, agreed that using suicide rates is a valid indicator of the availability of mental health care, because 90 percent of suicide victims are suffering from a mental disorder at the time of their death.

“The only way that we can change suicide [rates] is to recognize the disorders and see that [the people with these disorders] get treatment,” Clayton told Psychiatric News.

The report stated that age-adjusted suicide rates were the lowest in New York and New Jersey and highest in Montana, Alaska, and Nevada. Suicide rates are generally highest in Mountain region states and lowest in the Northeast.

Those findings largely dovetail with regional differences in the availability of mental health care, Clayton said. And the high rates in the less-populated Mountain states reflect research linking suicide and loneliness in the elderly.

“Aiming Higher: Results From the 2009 State Scorecard on Health System Performance” is posted at <www.commonwealthfund.org/Content/Publications/Fund-Reports/2009/Oct/2009-State-Scorecard.aspx>.