Duty-Hour Requirements Put Residents in Ethical Quandary

The challenge of overseeing compliance with restrictions on resident work hours—especially in the wake of new recommendations from the Institute of Medicine (IOM)—will require a change in educational culture to reconcile the “competing goods” of patient safety, continuity of care, and the teaching of professionalism.

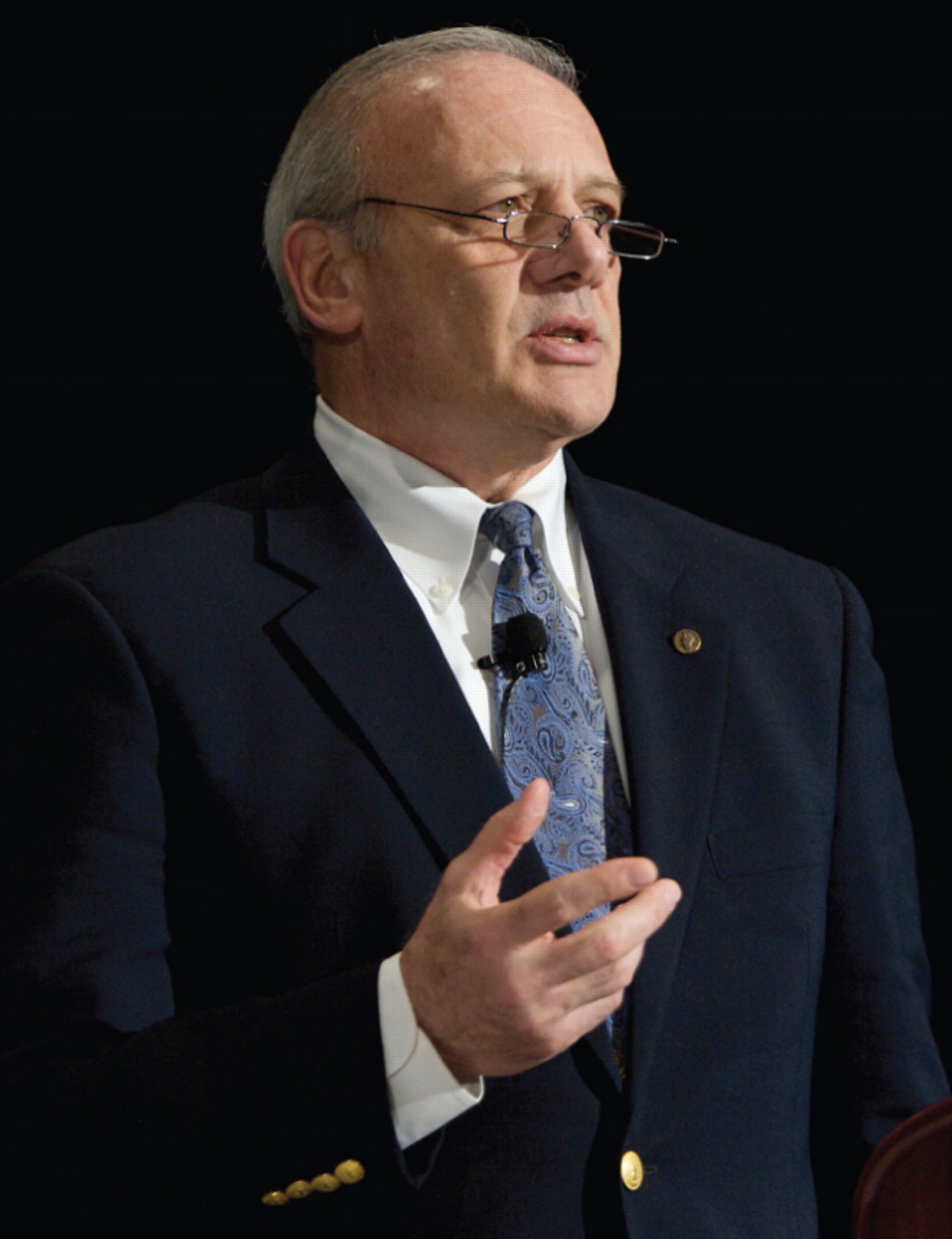

ACGME Chief Executive Officer Thomas Nasca, M.D., says that the issue of resident duty hours calls for reconciling “competing goods” of patient safety and resident education.

Photo courtesy of Rick Brandt for AADPRT

Medicine must meet the challenge of reconciling those goods through its own professional accreditation processes, or risk being regulated by the government, said Thomas Nasca, M.D., chief executive officer of the Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME), at last month's meeting of the American Association of Directors of Psychiatric Residency Training (AADPRT) in Tucson, Ariz.

Nasca said that the ACGME had already committed to revisiting its oversight of resident duty-hour compliance when the IOM issued its December 2008 report,“ Resident Duty Hours: Enhancing Sleep, Supervision, and Safety”—a report that he said “shook everyone up and angered many people.”

He noted that the problem of duty-hour restrictions has typically pitted concern for patient safety against continuity of care and the teaching of professionalism at a time when public funding of graduate medical education has been cut substantially and academic medical centers are caring for patients who are sicker and have more complex chronic conditions.

“The challenge for the ACGME is to be like Solomon in adjudicating what we view as competing goods,” Nasca said. “Up until this point it has been an argument—and there are no answers to an argument. This argument has been couched as a dichotomy: patient safety versus education.

“But we think this is a false dichotomy,” he continued.“ We need to start looking at what the data show [about resident work hours and patient safety] and come up with a set of requirements that make it better than what we have now. I think no one believes we have it right, and I think everyone agrees we are placing our residents in the ethical quandary of having to lie [about the hours they have worked] versus taking care of their patients. That is unacceptable.”

The IOM report did not recommend further reducing residents' work hours from the maximum average of 80 a week set by the ACGME in 2003, but did recommend reducing the maximum number of hours that residents can work without time for sleep to 16. That has the effect of increasing the number of days residents must have off and restricting moonlighting during residents' off hours, among other changes.

In addition, it recommended that the ACGME better monitor duty hours and that residency review committees set guidelines for residents' patient caseloads.

Nasca said the IOM recommendations also included one that would require the ACGME to report to the federal Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) regarding institutional compliance with duty-hour restrictions—a recommendation he warned against in stark terms.

“We are an educational accrediting body being asked to report to a payer,” Nasca said. “That is very concerning to us for lots of reasons—philosophical and operational.”

He stressed that if such a recommendation is made law, then the duty-hour monitoring should be kept separate from educational accrediting standards.

“We need to be very careful about this issue or we are going to give CMS the tool to introduce curricular hours directly into accrediting standards. This is not an idle threat. Soon we will have a Ministry of Health in the United States as they have in other countries where they don't have professional self-regulation.”

Nasca said that the ACGME has long experience with monitoring duty-hour restrictions and had committed, as early as 2003, to restructure its requirements in this area. He said that, typically, violations of work-hour rules do not occur in safety-net hospitals, but in institutions where the culture is such that “they don't want to satisfy” the rules.

At the same time, there are no currently meaningful sanctions against institutions whose only accrediting violations concern duty hours.

Nasca suggested as a remedy that the ACGME require, in addition to program evaluation by individual residency review committees, a second evaluation at the institutional level with the signatory being the chief executive officer of the institution.

There would be no fines and no impact on institutional accreditation, but the results of the review would be made public. “Those of you who know anything about CEOs know that they don't like bad grades [for their institutions] in the papers,” he said. “We believe this will solve the cultural problem.”

Nasca's remarks were part of an address about sweeping changes under way in how training programs are accredited in the future. Broadly, he described a movement away from a model of requiring minimal adherence to statutory regulations, to what he called “substantial compliance with leading-edge standards.”

While the former model encouraged institutions to aim low to comply with the law, the latter model is designed to create incentives for achieving excellence.

Yet the matter of monitoring duty hours—made urgent by the IOM and its recommendations—requires a more legalistic approach.

“Our challenge is to figure out how to apply a regulatory adherence concept to duty hours while not having the same thing in program accreditation and separating those two very clearly,” Nasca said. “And our goal is to do this while maintaining the public trust and not causing by our inaction the entry of a third party into the conversation.”

“Resident Duty Hours: Enhancing Sleep, Supervision, and Safety” is posted at<www.iom.edu/CMS/3809/48553/60449.aspx>.▪