More Psychiatry Residents Getting Enriched Neurology Education

Abstract

What do psychiatry residents want?

More neurology, according to surveys by the National Institute of Mental Health, and that's what several innovative programs around the United States are giving them.

At the 2010 APA annual meeting in New Orleans in May, residents and training directors from several universities reported on creative ways to provide that training.

The speakers noted that psychiatry residents often grow less confident about their knowledge of neurology as their residency progresses.

Formerly at the University of Wisconsin, psychiatry residents took two months of neurology in their first year, then saw nothing in that field until board exams loomed on the horizon in the last year of residency, said Art Walaszek, M.D., residency training director, vice chair for education, and an associate professor of psychiatry at Wisconsin.

Walaszek and chief resident Claudia Reardon, M.D., surveyed 172 other psychiatric residency programs and found that about 75 percent of the 57 responding programs offered didactic neurology instruction specifically for psychiatrists in training, concentrating on epilepsy, stroke, dementia, headache, and electroencephalography.

Most of the learning came in lecture form, but some programs also offered neuroradiology rounds and neuroanatomy lab sessions. Training came mostly in the first and last years of residency.

Only 55 percent of trainees surveyed, however, said they felt the neurology experiences were adequate.

“Psychiatry and neurology could be better integrated into grand rounds and in didactic instruction throughout the curriculum,” said Reardon.

University of Michigan residents have gone a step further, said chief resident M. Justin Coffey, M.D.

“Residency programs do a good job of teaching neurology to tests but not for patient diagnosis or care,” said Coffey.

Psychiatry residents at Michigan developed their own eight-week summer grand rounds, taught by neurology residents. The one-hour lectures covered clinical neuroradiology, abnormal movements, stroke and its symptoms, neuropsychiatry and dementia, epilepsy and nonepileptic seizures, pain, sleep and sleep disorders, and catatonia.

‘We Made It Fun’

The most significant aspect of the Michigan program was not its content but its faculty.

“We wanted good teachers but not research experts,” said Coffey. “Having the neurology residents teach helped allay the fears of being taught by the big names in the [neurology] department.”

The neurology residents enjoyed teaching, and the psychiatry residents found peer education an efficient and effective way to learn the fundamentals of clinical neurology.

“We made it easy, we made it useful, and we made it fun,” said Coffey.

The next step is to integrate this learning process into the year-round curriculum. In the future, the Michigan team hopes to combine peer teaching with peer learning by inviting social-work and nursing students and psychology post-docs to join the psychiatry residents in the audience.

Psychiatry Takes Back the Brain

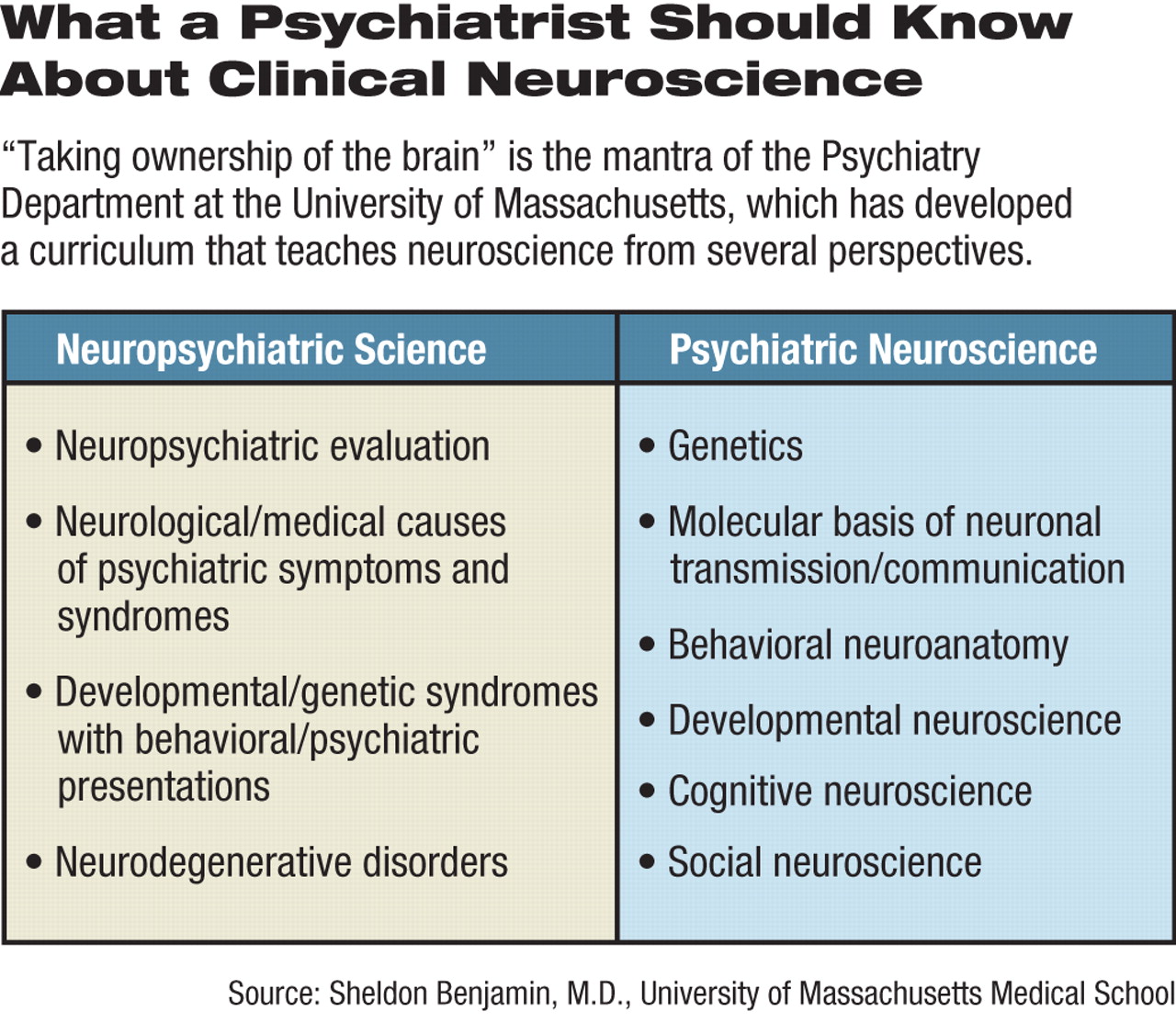

At the University of Massachusetts Medical School, the war cry in this campaign is “It's time for psychiatry to take back the brain.”

This approach might alleviate some of the stigma against psychiatry within the medical profession to the extent that it is produced by the perception that working in psychiatry means “not doing science,” suggested University of Massachusetts psychiatry training director Sheldon Benjamin, M.D.

His department has worked up a range of required and elective training segments, plus a biological psychiatry seminar for third- and fourth-year residents.

At the program's core are month-long rotations in adult inpatient neurology (or pediatric neurology for child psychiatry residents), neurology inpatient consultation, and neuropsychiatry.

Residents can also attend an elective neuropsychiatry seminar open to all residents.

“The objective is not to do neurology but to be able to order, interpret, and use results from neuropsychological testing, structural imaging, EEGs, and evoked potentials,” said Benjamin, who is a neurologist as well as a psychiatrist.

The department also offers a six-year combined neuropsychiatry program that includes a year of medical internship, two years each of psychiatry and neurology, and a final year of neuropsychiatry.

All this interaction benefits both the residents and their patients, said Benjamin.

“Now psychiatry residents see neurology residents as colleagues,” he said. “Co-teaching helps break down barriers between the two fields. When psychiatrists help the neurologists take care of their difficult patients, we make friends forever.”

Finally, waiting until residency to address the gap between the two fields may not be the only way of bridging it, said several speakers.

They noted that collaborations might usefully begin in medical school classrooms, or even in the premedical curriculum, to begin instilling the ever-growing interaction between neurology and psychiatry, they said.