Study Examines Relationship of Arrests, Mental Illness

Abstract

Fewer than 10 percent of former inmates diagnosed with serious mental illness during their parole period were originally arrested as a result of actions directly attributable to an untreated mental illness, according to a study in the December 2010 Psychiatric Services.

That small percentage reflects previous research on the link between crime and mental illness and may challenge the “criminalization” hypothesis used to explain the large percentages of prison inmates with mental illness.

The research examined the hypothesis that people with serious mental illness who are left untreated by underequipped public mental health systems are caught up in the criminal-justice system when their symptoms—such as psychosis-induced violence, disturbed behavior on the street, or poverty-related crimes—lead the police to take them into custody. Once in the justice system, these individuals are either not recognized as mentally ill and languish in prison, or they are diagnosed and provided costly but often inadequate treatment within the penal system.

“The implicit assumption is that this population is involved in the criminal-justice system chiefly or solely because of untreated mental illness,” wrote Jennifer Skeem, Ph.D., a professor of psychology and social behavior at the University of California, Irvine, and colleagues.

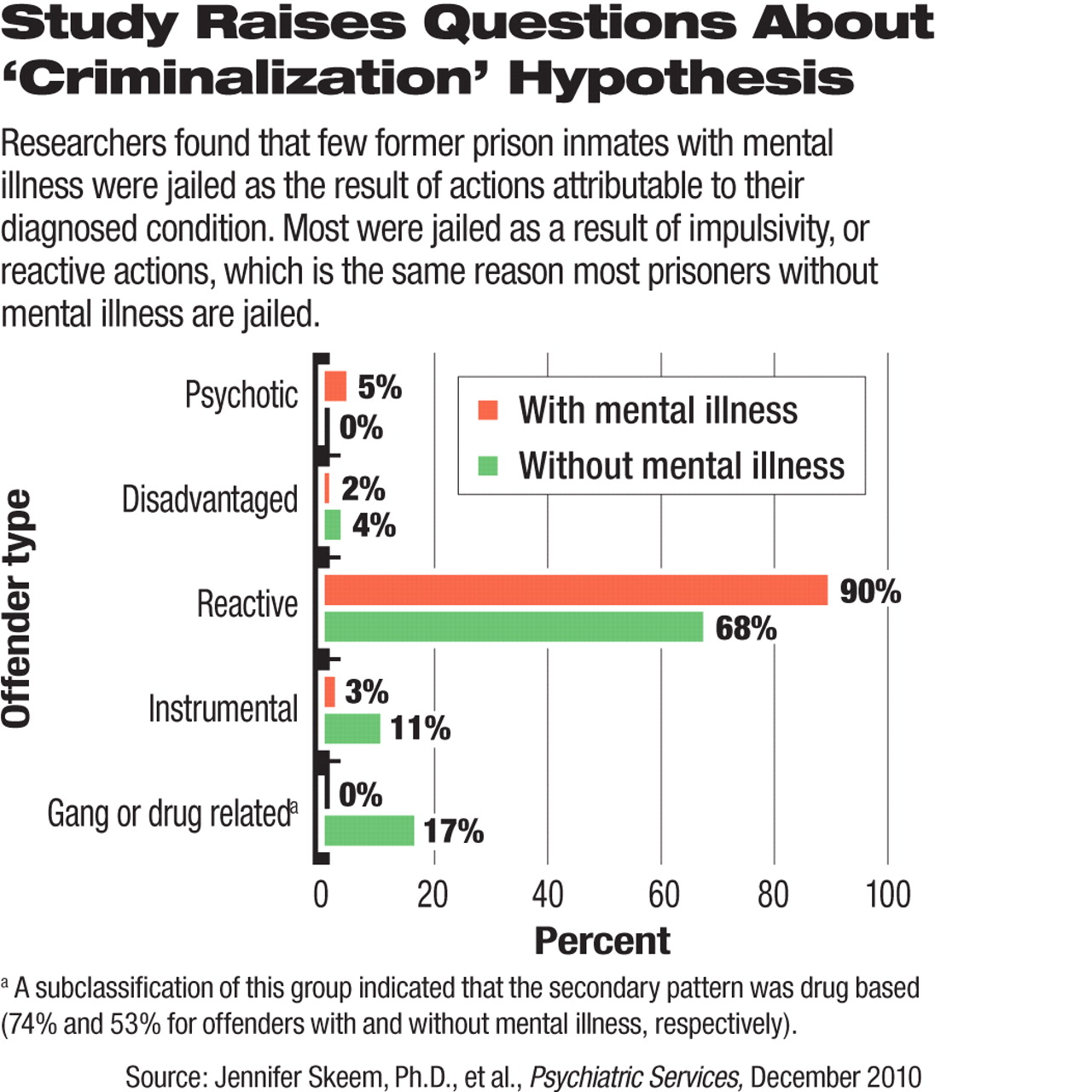

For their study, Skeem and colleagues studied the arrest histories of 111 ex-offenders who were diagnosed with a serious mental illness (including schizophrenia or another psychotic disorder, bipolar disorder, and major depressive disorder) upon their release from a California jail. The researchers found that psychiatric symptoms “were a unique criminogenic need that were related directly to offending” in only a small minority (7 percent) of these former inmates. In contrast, about 90 percent of mentally ill ex-inmates were jailed as a result of “emotionally motivated responses to perceived provocation,” or impulsivity, which the researchers classified as “reactive” offenses.

Reactive offenses also led to the arrest of a majority (68 percent) of a comparison group of 109 demographically matched ex-offenders without serious mental illness, whom the researchers also studied.

The findings may challenge some aspects of the criminalization hypothesis, which has led to many initiatives (such as mental health courts and jail-diversion programs) explicitly aimed at avoiding the incarceration of mentally ill people.

However, law experts interviewed for this article said that the Psychiatric Services study is insufficient to seriously undermine efforts based on the criminalization hypothesis.

The researchers' “conclusion is an oversimplification of a complex interaction among symptoms of mental illness, the destabilizing effects of mental illness on persons in the community, and community resources,” wrote Howard Zonana, M.D., a professor in the Department of Psychiatry at Yale and a clinical adjunct professor at the Yale Law School, in an interview with Psychiatric News.

Paul Appelbaum, M.D., generally agreed. Appelbaum, a former APA president, is the Elizabeth K. Dollard Professor of Psychiatry, Medicine, and Law and director of the Department of Psychiatry's Division of Law, Ethics, and Psychiatry at the College of Physicians and Surgeons at Columbia University.

“If it were really symptoms, especially psychotic symptoms, that were driving criminality, one would expect those variables to best predict future violence,” Appelbaum told Psychiatric News. “But they don't.”

However, Appelbaum allowed that the Skeem study could be part of a “paradigm shift” in the understanding of violence and its connection to mental disorders.

“The new paradigm suggests that merely treating mental disorders may be insufficient to reduce criminality, including violence, unless specific criminogenic factors are addressed as well—for example, anger management and cognitive therapy for criminal cognitions,” Appelbaum said. “That is not a reason to reduce efforts to treat major mental disorders in the offender population, but it is recognition that ordinary clinical treatments may not be enough.”

Although the researchers cautioned that more studies are needed to draw “definitive conclusions,” their findings indicated to them that the diversion and treatment approach for people with untreated mental illness, which is widely used and advocated by clinicians and policymakers, may prevent future arrests only for a small subset of prisoners with untreated psychiatric illness.

“For most offenders with serious mental illness, however, services that can and should be delivered to improve clinical outcomes may not translate into reduced recidivism,” Skeem and colleagues suggested.

But the large reactive category may be so broad that it also could include many parolee actions stemming from less serious mental illnesses, according to Zonana.

“The ‘reactive’ category . . . is one that may have significant contributory factors stemming from mental disorders that may not reach psychotic proportions,” Zonana noted.

The findings of Skeem and colleagues echo previous research, including a study in the June 2006 Psychiatric Services by John Junginger, Ph.D., and colleagues, that found that few of the arrestees they studied who had a serious mental disorder were incarcerated because of behavior directly or even indirectly attributable to mental illness. That study of 113 participants in a Hawaii jail-diversion program for people diagnosed with a schizophrenia spectrum disorder or a major mood disorder and co-occurring substance use disorder found that only 8 percent were arrested for illness-related behaviors.

William Fisher, Ph.D., a professor of psychiatry at the University of Massachusetts Medical School who has studied the incarceration of people with mental illness, said that research like the Skeem study is needed to test the criminalization hypothesis.

“To me the criminalization concept has always been something of a ‘black box’ that links a person's status as an individual with a psychiatric disorder to elevated risk of arrest, but says little about what are the likely multiple causal linkages that connect those two factors,” Fisher told Psychiatric News. “Factors such as ‘hostility,’ ‘disinhibition,’ and ‘emotional reactivity’ play out in various social contexts, and learning what those are may help in developing methods for reducing their role in criminal justice involvement. I hope this paper will encourage the research community to take this on.”

After analyzing their data, Skeem and her colleagues concluded that reducing recidivism for the majority of people with serious mental illness may require not only treatment for their psychiatric conditions but also participation in programs used to reduce recidivism among former prisoners without psychiatric illness. Such programs attempt to reduce impulsivity and positive attitudes toward crime among former inmates.

Fisher echoed the study authors' call for additional examinations of criminalization, including an examination of the ways in which convicts' symptoms of psychiatric illness combine with their social environment and other factors to culminate in encounters with law enforcement.

“Analyzing Offense Patterns as a Function of Mental Illness to Test the Criminalization Hypothesis” is posted at <http://ps.psychiatryonline.org/cgi/content/full/61/12/1217>.