GHRH Improves Cognition in Mildly Impaired Adults

Abstract

It looks as if growth hormone, long used to treat children deficient in that substance, has new and promising uses that will help many more people than the young.

That is because the focus has shifted to growth hormone-releasing hormone (GHRH)—the hypothalamic factor that controls the release of growth hormone from the pituitary gland. The Food and Drug Administration has approved its use for treating growth-hormone deficiency and lipodystrophy related to human immunodeficiency virus infection.

But the excitement does not stop there. Six years ago, Michael Vitiello, Ph.D., a professor of psychiatry at the University of Washington, and his colleagues found in a six-month randomized, controlled trial of 89 healthy older adults that daily injections of GHRH improved executive function significantly more than a placebo did. They have now not only confirmed those results in a larger study, but have extended them to subjects with mild cognitive impairment.

The results were published online August 6 in the Archives of Neurology.

The study population included 137 adults aged 55 to 87, of whom 76 had normal cognitive status and 61 of whom had mild cognitive impairment.

The subjects self-administered daily subcutaneous injections of a synthetic analog of human GHRH (1 mg/d) or a placebo 30 minutes before bedtime for 20 weeks. At baseline, at weeks 10 and 20 of treatment, and after a 10-week washout period (week 30), cognitive tests were administered. The cognitive test performances at the start of the study were then compared with those at 10 weeks, 20 weeks, and 30 weeks.

The executive-function results for the group that had received GHRH were significantly better than for the group that had received a placebo.

“Even though the healthy adults outperformed those with mild cognitive impairment over all, the cognitive benefit relative to placebo was comparable for both groups,” the researchers indicated. Thus, even though mild-cognitive-impairment subjects in the GHRH group did not perform as well as healthy subjects in that group by the end of the study, GHRH treatment had improved their cognition to a comparable amount considering what it had been at the start of the study, Laura Baker, Ph.D., an associate professor of psychiatry at the University of Washington and lead researcher of the study, explained to Psychiatric News. “We were surprised that the cognitive benefits of GHRH were equally robust for healthy older adults and for adults with mild cognitive impairment,” she said.

Thus, “20 weeks of GHRH administration had favorable effects on cognition in both adults with mild cognitive impairment and healthy older adults,” Vitiello, Baker, and colleagues concluded.

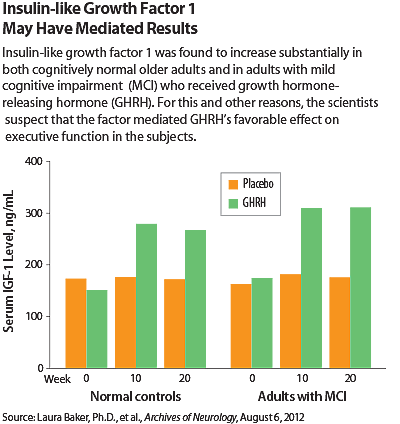

Although the researchers are not sure exactly how GHRH benefits cognition, they suspected, on the basis of blood tests they had performed on the subjects, that insulin-like growth factor 1 may have been involved. Specifically, GHRH treatment increased this factor significantly in subjects who received it, and a deficit in the factor is linked to poorer executive function and poor short-term memory. The factor is also known to cross the blood-brain barrier, bind to receptors in the brain, and have favorable effects on neurobiological processes compromised by aging and Alzheimer’s disease.

“This is a well-conducted trial by an outstanding group of investigators with expertise in cognitive disorders of later life,” APA President Dilip Jeste, M.D., chair in aging at the University of California, San Diego, told Psychiatric News. “Currently there are no Food and Drug Administration–approved treatments for either aging-associated cognitive impairment or mild cognitive impairment. Therefore, these results are highly promising.

“However, caution is warranted in interpreting the general clinical relevance of these findings,” Jeste continued. “The drug effects were of relatively small magnitude, and their relevance to everyday functioning remains unclear. It is not known what the efficacy and safety would be if the treatment were continued for more than five months. In sum, the results are encouraging, but need replication in other samples before GHRH can be recommended for routine clinical management of aging-associated cognitive impairment or mild cognitive impairment.”

The study was funded by the National Institutes of Health and the Department of Veterans Affairs.

“Effects of Growth Hormone-Releasing Hormone on Cognitive Function in Adults With Mild Cognitive Impairment and Healthy Older Adults” is posted at http://archneur.jamanetwork.com/article.aspx?articleid=1306261.