Imaging Studies Document Schizophrenia’s Devastation

What does schizophrenia do to the human brain? A lot of damage, according to a study conducted by Paul Thompson, Ph.D., an assistant professor of neurology at the University of California at Los Angeles, and his colleagues. The study was published in the September 25 Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

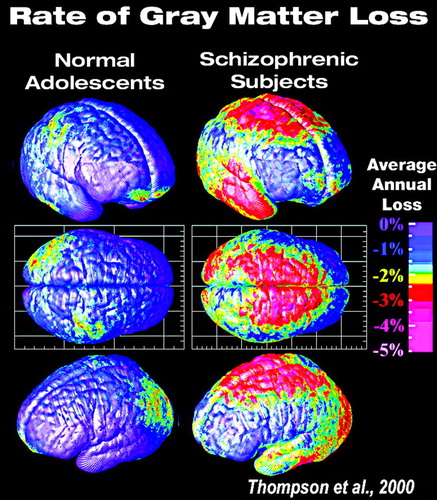

Over a five-year period, Thompson and his coworkers did MRI scans of the brains of 12 teenagers diagnosed with schizophrenia. They then compared results from one scan with those from the next with the use of a computational cortical pattern-matching strategy that aligns corresponding locations on the cortical surface, across time and across subjects. The procedure thus allowed them to map an individual’s gray-matter loss over time and compute average rates of any gray-matter loss for the group over time.

Over a five-year period, Thompson and his coworkers did MRI scans of the brains of 12 teenagers diagnosed with schizophrenia. They then compared results from one scan with those from the next with the use of a computational cortical pattern-matching strategy that aligns corresponding locations on the cortical surface, across time and across subjects. The procedure thus allowed them to map an individual’s gray-matter loss over time and compute average rates of any gray-matter loss for the group over time.

The subjects did lose gray matter over the five-year period, the researchers found. First to be affected were the parietal lobes. And then came the temporal lobes, frontal lobes, and frontal eye fields. The wave of destruction, in other words, moved forward in the brain. By the end of the five-year period, the wave of devastation had engulfed the entire brain. “It was as if a forest fire had swept through,” Thompson said in an interview with Psychiatric News.

“We were extremely surprised by these findings,” Thompson admitted. “Basically we were working on a technique that provides a new way to detect and visualize very small changes in the brain, which are often a sign of a disease. So we expected that we might find differences in our subjects’ brains over time, but we didn’t think we would find such dramatic ones.”

Another intriguing aspect of their discoveries, Thompson said, is that gray-matter loss appeared to be a true reflection of disease progression. Positive symptoms such as hallucinations, bizarre thinking, and sensory disturbances; negative symptoms such as depression and social withdrawal; and global function were associated with gray-matter loss. Patients with the worst disease symptoms also had the greatest amount of gray-matter loss.

Also, damage to particular brain areas coincided, at least to some degree, with disease symptoms that one would have expected to arise from damage to those particular brain areas. For instance, severity of auditory hallucinations was linked with the severity of gray-matter loss in the temporal lobes, which are important for the appreciation of speech.

Loss Among Normal Teens

The scientists likewise compared the status of gray matter in the brains of the 12 teenagers they studied with the status of gray matter in the brains of 12 mentally healthy teens over the same five-year period. Overall, the healthy teens lost some gray matter, at a rate of about 0.5 percent to 1 percent a year, mostly in the parietal lobes. The loss in the teens with schizophrenia was much greater—about 2 percent a year.

What does the difference in loss between these two groups mean? Thompson acknowledged that he isn’t sure. “But wouldn’t it be intriguing,” he asked, “if schizophrenia were a disorder of teenage brain development? After all, it hits in the late teens or early 20s, and nobody knows the cause. The fact that normal teens lose some gray matter leads to the theory that this process could be sped up, or abnormal, in schizophrenia. The genes that regulate the loss could be altered, or some nongenetic trigger, such as a virus, could interfere with healthy brain development and trigger a pattern of loss.”

In addition to following gray-matter changes in teens with schizophrenia and in mentally healthy teens over five years, the investigators also tracked for five years gray-matter status in 10 teens who, like the subjects with schizophrenia, were taking antipsychotic medications, yet who had not been diagnosed with schizophrenia. These subjects were receiving antipsychotic medications to help control mood disorders and aggression.

The reason the researchers included these subjects in their study was to determine whether antipsychotic meds might have been causing any gray-matter changes noted in the teens with schizophrenia. And to a large extent this possibility appears to have been ruled out, since the pervasive gray-matter loss seen in the schizophrenia subjects over the five-year period was not found to occur in these subjects who were not diagnosed with schizophrenia.

Nonetheless, there was discrete gray-matter loss in the frontal lobes of the nonschizophrenia subjects over the five-year period. So the question is: What does this loss mean? “It is possible,” Thompson replied, “that this group had a slightly accelerated loss of brain tissue relative to normal subjects, especially since normal teens lose tissue anyway, at least to a very small degree. On the other hand, we cannot rule out the possibility that antipsychotic medications were having an effect in this region, so further study of this particular group is needed.”

Implications of Treatment

The results of this investigation, Thompson believes, should also set the stage for some provocative discoveries. For instance, if it takes five years for schizophrenia to significantly affect the brain, then there should be a five-year window where new medications can be tried to see whether they might be able to halt gray-matter loss. Also, by visualizing subtle brain changes in relatives and identical twins of patients with schizophrenia, and then comparing such changes with changes already noted in the patients themselves, researchers might be able to pinpoint the first brain areas affected by the schizophrenia disease process.

One thing that Thompson and his team are especially eager to test is whether the wave of gray-matter loss entering the frontal eye fields of schizophrenia patients coincides with a worsening of eye-tracking ability. The frontal eye fields control eye movement, and difficulty honing in on what aspect of a scene is important is a well-known schizophrenia symptom.

The study was underwritten by the National Institutes of Health.

The report, “Mapping Adolescent Brain Change Reveals Dynamic Wave of Accelerated Gray-Matter Loss in Very-Early-Onset Schizophrenia,” can be read online at www.pnas.org/cgi/content/full/98/20/11650. ▪

Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2001 98 11650