Study Finds Less or No Medication After Psychosis Fosters Recovery

Abstract

A long-term study adds to evidence that recovery from psychosis is possible, and the key may lie in using less antipsychotic medication after a psychotic episode ends.

If remitted first-episode psychosis patients reduce their antipsychotic medication dosage or discontinue it, they will experience a higher relapse rate than remitted first-episode patients who continue on a maintenance antipsychotic medication dosage, studies have found. However, all of these studies were limited to two years or less.

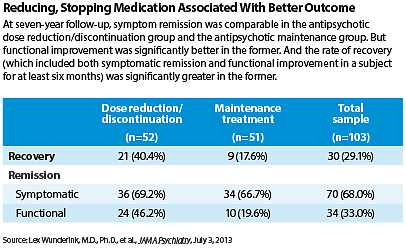

Now a new study that lasted seven years has confirmed that result—a higher relapse rate during the first two years in the lower-dosage/discontinuation group than in the maintenance group. But this new study has also found something surprising: whereas the former group had the same rate of symptom remission at seven years as the latter group, it had significantly greater functional improvement and recovery at seven years.

The study was published online July 3 in JAMA Psychiatry. The lead researcher was Lex Wunderink, M.D., Ph.D., a psychiatrist at the University Medical Center Groningen in the Netherlands and part of the Early Intervention in Psychosis team at Friesland Mental Health Services.

The focus of this study was a total of 103 patients with antipsychotic-medication-induced remission from a first-episode psychosis. After six months of sustained remission, they were randomly assigned for 18 months to an antipsychotic medication dose reduction or discontinuation strategy or to an antipsychotic medication maintenance strategy.

After that, treatment was at the discretion of the individuals’ clinicians. Then five years later, or seven years from the start of the study, the researchers conducted an interview with each subject to determine outcome.

The subjects were evaluated on the number of relapses they had experienced during the previous five years. Relapses were retrospectively assessed by interviewing the patients and checking their information with that of their attending clinicians, their medical records, and their admission and prescription data. Relapse was defined as a symptom exacerbation during at least one week.

The Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale (PANSS) was used to measure subjects’ symptoms during the previous six months. The Groningen Social Disability Schedule (GSDS) was used to measure disability in various domains—self-care; housekeeping; family, partner, and peer relationships; community integration; and work function. In addition, subjects were evaluated for recovery-related factors such as experiencing bothsymptomatic remission and functional improvement as measured by the PANSS and GSDS for at least six months preceding the seven-year interview.

The initial relapse rates were twice as high in the dose reduction/discontinuation group as in the maintenance-therapy group. But the curves then approached each other and came on par at about three years of follow-up. From then on, the relapse rates did not differ significantly between the two groups.

Moreover, by the seven-year follow-up interview, the dose reduction/discontinuation group had experienced significantly more functional improvement than the maintenance group had. And also by the seven-year interview, 40 percent of the dose reduction/discontinuation group had recovered from their illness, whereas only 18 percent of the maintenance group had—a significant difference.

Results Unexpected

“These findings were quite surprising to all of us,” Wunderink told Psychiatric News. “We did not expect to find any significant effect of the original treatment strategies after seven years of follow-up, because from the original trial’s endpoint to follow-up five years later, the patients’ treatment had been completely at the discretion of the attending clinicians, and functional outcome after two years follow-up was not significantly different.”

Remitted first-episode psychosis subjects were assigned to either maintenance antipsychotic medication or a dose-reduction/discontinuation of antipsychotic medication. During the next five years, treatment was at the discretion of their physicians. At the end of that time, the dose-reduction/discontinuation group showed a higher rate of recovery than did the maintenance group. | |||||

A schizophrenia expert not affiliated with the study says that “these findings raise questions about the benefits of maintenance antipsychotics” but notes that some of the subjects who received a dose reduction/discontinuation strategy continued on medication, although at a smaller dose. “Thus, it may be best for the clinician to consider a minimum effective dose strategy rather than total discontinuation.” | |||||

The lead researcher shares that opinion: “The results show that it might be the best strategy in first-episode patients who are sufficiently free of symptoms during six months (meet remission criteria) to follow a dose-reduction strategy. This strategy will require close monitoring, and if symptoms recur, then the dose will have to be adequately adjusted.” | |||||

“Of course the results will have to be replicated to change guidelines,” Wunderink continued. “But the results show that it might be the best strategy in first-episode patients who are sufficiently free of symptoms during six months (that is, meet remission criteria) to follow a dose-reduction strategy. This strategy will require close monitoring, and if symptoms recur, then the dose will have to be adequately adjusted.”

So if after remission is achieved, an antipsychotic dose reduction/discontinuation does promote recovery, how might it do so? One possibility, Wunderink and his colleagues suggested, is that antipsychotics not only counter psychosis, but also compromise important mental activities such as alertness, curiosity, drive, and executive function. Another possibility, they said, is that being in the antipsychotic-reduction/discontinuation group motivated subjects to actively participate in their own recovery.

Maintenance Might Not Be Best Course

This important study suggests that an antipsychotic dosage reduction/discontinuation (DR) strategy in remitted first-episode psychosis patients might have advantages at seven-year follow-up on recovery and functional remission, but not in symptom remission,” Matcheri Keshavan, M.D., a professor of psychiatry at Harvard Medical School and a schizophrenia recovery expert, said during an interview. “These findings raise questions about the benefits of maintenance antipsychotics. [However,] these findings should be considered with caution because of three caveats.”

The first, he said, is that the “study defined first-episode psychosis broadly (as schizophrenia or other psychoses). We already know that some patients, such as those with brief psychotic disorders and psychoses not otherwise specified, may do well without long-term antipsychotics. Thus, the findings cannot be generalized to schizophrenias defined narrowly.”

The second, he said, is that “some patients in the DR strategy continued to be on medications, albeit at a smaller dose. Thus, it may be best for the clinician to consider a minimum effective dose strategy rather than total discontinuation in many patients.”

And finally, he said, “less than half of patients in either strategy had achieved recovery at follow-up, highlighting, as the authors themselves point out, the need for alternative pharmacological, or perhaps psychosocial, interventions.”

The research was funded by unconditional grants from Janssen-Cilag Netherlands and Friesland Mental Health Services. ■

An abstract of “Recovery in Remitted First-Episode Psychosis at Seven Years of Follow-up of an Early Dose Reduction/Discontinuation or Maintenance Treatment Strategy” is posted at http://archpsyc.jamanetwork.com/article.aspx?articleid=1707650.