Study Finds No Link Between Deployment, Suicide

Abstract

Separation from the military was strongly associated with an increased risk of suicide, suggesting more could be done to support personnel during this transition period.

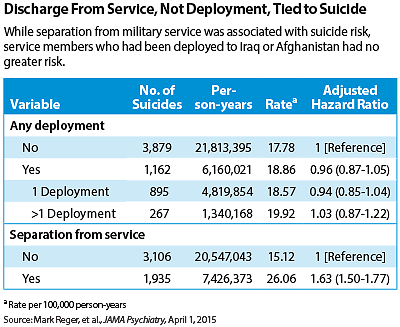

A study of the 3.9 million U.S. military service members who served in Iraq or Afghanistan finds that suicide mortality was associated with discharge from service but not with deployment to the war zones.

The retrospective cohort study included personnel in the Army, Marine Corps, Air Force, or Navy, including National Guard and reservists, who served between October 7, 2001, and December 31, 2007. Suicide data were tracked until the end of 2009. Those who were deployed went to any of several Middle Eastern countries or to surrounding oceans to fight in Iraq or Afghanistan or to support the war efforts there.

Overall, service members who deployed had no greater risk of suicide than those who had never deployed, concluded Mark Reger, Ph.D., of the National Center for Telehealth and Technology at Joint Base Lewis-McChord in Tacoma, Wash., and colleagues in JAMA Psychiatry, online April 1.

However, separation from military service was strongly associated with suicide risk, they said. Rates were 15 suicides per 100,000 person-years for those in uniform, a figure that jumped to 26 per 100,000 person-years following separation.

“Transitions are generally high-risk periods for suicides,” said retired Army Col. Elspeth Cameron Ritchie, a former Army psychiatrist. “We need to pay attention to the transition period when people are leaving military service. Many are discharged with little safety net to support them.”

The long-promised “seamless transition” from the Department of Defense health care system to the Veterans Health Administration has not happened yet, and such a connection may take time, said Ritchie.

Increased time in the Armed Forces also reduced the risk of suicide, according to Reger and colleagues. Troops with less than a year’s service had more than double the rate of suicide compared with those who completed between four and 20 years of service.

The present study is likely to be compared with the Army Study to Assess Risk and Resilience in Servicemembers (Army STARRS)—a multiyear project investigating suicide in the U.S. Army, which last year reported an elevated suicide risk among currently and previously deployed soldiers.

“These two studies cover different populations, different times, with different deployment experiences,” said Army STARRS principal investigator Robert Ursano, M.D., a professor and chair of psychiatry at the Uniformed Services University of the Health Sciences in Bethesda, Md., in an interview. Compared with the Army STARRS study, which examined only those on active duty in the Army in 2004 through 2009, the JAMA Psychiatry study examined all personnel who served during that era, on or off active duty.

Reger and colleagues also noted that they did not have access to data about combat exposure or the mental health status of those personnel, another important difference between the two studies, said Ursano.

“Army combat units on the ground in Iraq faced a very different environment compared with Air Force personnel stationed in Kuwait or Navy sailors on a ship at sea,” he noted. “It’s well known that combat exposure increases the risk for mental health problems, and mental health problems increase the risk for suicide.”

Both the fact and the circumstances of discharge may prove problematic for some service members, for several reasons.

“Loss of a shared military identity, difficulty developing a new social support system, or unexpected difficulties finding meaningful work may contribute to a sense that the individuals do not belong or are a burden on others,” wrote Reger and colleagues.

Someone whose hopes and dreams have been invested for years in a military career may feel unmoored following separation from the service, regardless of the cause, said Ritchie.

“People who don’t do well in the service and are discharged are at high risk, but it’s a chicken-and-egg situation,” she added. “Behavioral problems and suicidality may have led to the discharge.”

Better outreach to service members at this high-risk time through veterans service organizations, educational institutions, and workplaces is needed to reduce the risk of suicide, Ritchie said. ■

“Risk of Suicide Among U.S. Military Service Members Following Operation Enduring Freedom or Operation Iraqi Freedom Deployment and Separation From the U.S. Military” can be accessed here.